IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH

(HIGH COURT DIVISION)

arbitration Application No. 16 of 2009

Decided On: 31.01.2011

Appellants: Stx Corporation Ltd.

Vs.

Respondent: Meghna Group of Industries Limited

**Hon’ble Judges:**Mamnoon Rahman, J.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Mr. Ajmalul Hossain, QC., Senior Advocate with Mr. A.B.M. Siddiqur Rahman Khan, Mr. Syed Afzal Hossain and Mr. Muhammad Saifullah, Advocates

For Respondents/Defendant: Dr. Sharif Bhuiyan, Advocate with Mr. Tanim Hussain Shawon, Advocate

Subject: arbitration

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

Acts/Rules/Orders: Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 115 (2); Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 44A; Constitution Of The People’s Republic Of Bangladesh - Article 111.

Disposition:

Application Dismissed

Citing Reference:

Discussed

6

Mentioned

29

Case Note:

Generally all statutes are to be construed according to the plain, literal and grammatical meaning of the words and one should not import words into an enactment which are not therein. When words in a statute are clear and unambiguous they should be construed according to their tenor and meaning for that reflects the intent and purpose of a legislation. It is only where the meaning is incomplete or ambiguous, it is possible to construe it in a way to remove absurdity so as to give effect to the purpose of a legislation. Where literal meaning of the words used in a statute is unambiguous and clearly conveys a reasonable meaning, the court has no power to read into the statute words for conveying a different meaning. The rule of literal construction requires the court to construe a provision of a statute according to the ordinary and natural meaning of the language used by the legislature as the language so applied best declares the intention of the legislature and recourse to any other principle of interpretation is unnecessary.**

It has been argued by the petitioner that while deciding the case of HRC Shipping Limited vs. M.V. X-Press Manaslu and others, reported in 12 MLR (2007) 265, this Court, considering all aspects of the Act of 2001 as well as international conventions relating to arbitration specially the Model Law and lastly the decision passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia Case, came to a conclusion that the provisions of the Act of 2001 is also applicable to a foreign arbitration. On perusal of the judgment as referred herein it appears that his Lordship considered a series of judgments passed by this Court as well as our Apex Court regarding the applicability of the Act of 2001 to a foreign arbitration but his Lordship considered the Model Law, the international conventions and the very spirit and intention of the purpose of amendment of the Act of 2001 and certain decisions of Indian jurisdiction, which include the case of Bhatia International-Vs-Bulk Trading S.A. and another reported in AIR 2002 (SC) 1432 and came to a conclusion that since the legislature did not mention anything excluding the jurisdiction relating to foreign arbitration, the provision of Act of 2001 is also applicable to a foreign arbitration. Thus, his Lordship exercising the power conferred under section 10 of the Act of 2001, stayed proceeding relating to a foreign arbitration. Admittedly the aforesaid decision has not been challenged before the Apex Court, and on a plain reading of the same it appears that the same is an exhaustive one.*

It appears that in the said case the Court relied upon the Bhatia case as mentioned hereinabove. On perusal of the judgment passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case it appears that the Indian Supreme Court considered the provision of the interpretation of statute, the intention of the legislature, the consequence of law, the ambit, scope and the reasons behind enacting the arbitration Act of 1996 and the Indian Supreme Court came to a conclusion that on the plain reading of section 2, which is similar to our section 3, since the legislature by express provision did not oust the application of the Act to a foreign arbitration, it cannot be said that the Indian arbitration Act is not applicable to a foreign arbitration. However, in the said case, Indian Supreme Court came to a conclusion that if the parties by express or implied manner did not exclude the jurisdiction in that case the provisions of the Indian Act shall apply.**

It appears that the same point was raised before the Indian Supreme Court once again in the case of Dozco India P. Ltd. vs. Doosan Infracore Co. Ltd. in arbitration Petition No. 05 of 2008, wherein the single Judge accepted the decision of the Indian Supreme Court in interpreting the Indian arbitration Act of 1996 in such a manner as to provide application to a foreign arbitration unless the parties either in express or implied manner excluded the same. On perusal of the Dozco case, it appears that considering Articles 22 and 23 of the arbitration agreement in question in the Dozco case the court came to a conclusion that since by express manner the parties excluded the jurisdiction, the provision of Act of 1996 shall not be applicable in that particular case.*

From a combined reading of the judgments passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case and the Dozco case as well as the HRC case, there is no room to have any doubt about the application of the Act of 2001 to a foreign arbitration. Apart from that, on perusal of the judgment passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the case of Venture Global Engineering vs. Satyam Computer Services Ltd. and another reported in 4 SCC (2008) 190, it appears that in that case also the Court accepted the principle laid down in the Bhatia case and came to a conclusion that part-I of the Act of 1996 is applicable to International Commercial arbitration held outside India, unless the same has been excluded by an agreement between the parties. Therefore, unless applicability of any provision has been excluded specifically, the parties can invoke the provision of the Indian arbitration Act of 1996.**

Furthermore, the Model Law and the arbitration law of Singapore adopted the provision of interim measures in clear language. The English arbitration Act of 1996 also makes express provision for passing interim order by the local courts in relation to a foreign arbitration where the place is beyond the local jurisdiction.**

Industry: Services Sector

JUDGMENT

Mamnoon Rahman, J.

- The petitioner, a company incorporated under the laws of South Korea, having its registered office/ headquarters in South Korea, engaged in the business of shipping, energy, mineral oil and others filed this application invoking Section 7ka of the arbitration Act of 2001 (hereinafter referred to as Act of 2001) praying for interim relief by way of injunction restraining the respondents No. 3-4 from transferring/selling or disposing of their properties mentioned in the schedule of the application pending disposal of the arbitration proceeding now pending before the competent Arbitrator in Singapore. After preliminary hearing, this Court vide order dated 14.12.2009, admitted the application and served show cause notices regarding the properties in question and passed an interim order of injunction restraining the respondents No. 3 and 4 from dealing with the properties mentioned in schedule A, B and C of the application under Section 7Ka of the Act of 2001.

- The short facts leading to the initiation of this application are as follows. The petitioner company entered into an agreement with the respondent No. 1 for supply of hot rolled steel. However, the parties failed to proceed with performance of the contact resulting in the issuance of termination letter by the petitioner company to respondent No. 1. Since there was a dispute and there was a provision for arbitration, the petitioner served notice upon the respondent No. 1 by invoking clause 5 of the contract in question and accordingly the competent arbitration tribunal is in seisin of the matter by way of arbitration. During pendency of the arbitration process, the petitioner filed this application for getting interim order restraining the respondents from transferring valuable properties and other assets till disposal of the arbitration proceeding on the apprehension that if the petitioner failed to get any interim order of injunction, and in the event of disposal of the property, the arbitration itself will become fruitless and of no use and the very purpose of the alternative dispute resolution will be frustrated. Since there is a provision for interim injunction in Section 7Ka of the Act of 2001, the petitioner invoked the same before this Court.

- The respondents No. 3 and 4 contested the application by filing affidavit in opposition. It also appears that the respondent No. 3 and 4 preferred 2 separate applications for vacating the interim order against which the petitioner filed separate affidavits in reply. The petitioner also filed 2 supplementary affidavits annexing various documents including the correspondence between the parties as well as with the arbitration tribunal. The case of the respondents No. 3 and 4, in short, is that the instant application is manifestly misconceived and not maintainable, and hence is liable to be summarily rejected with costs for the following reasons:

a) No injunction under Section 7Ka of the arbitration Act, 2001 can be granted in respect of the properties personally owned by the respondents No. 3 and 4 inasmuch these are not the subject matter of the Contract dated 28.4.2008 (“The Contract”), which is apparent on the face of the Contract.

b) The ad-interim injunction was sought, and has been granted ex parte against two individuals, i.e. respondents No. 3 and 4, who are not parties to the Contract.

c) The party to the Contract is stated to be “Meghna Group of Industries”, but the application has been filed against Meghna Group of Industries Limited, a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 1994, which is not a party to the Contract.

d) Without prejudice to the foregoing, it is stated that the purported notice of arbitration dated 5.12.2009 on the basis of which the instant application has been filed is otherwise manifestly defective. The petitioner has admitted that neither a “Singaporean Commercial arbitration Board” nor any “Commercial arbitration Rules of the Singaporean Commercial arbitration Board”, as referred to in the arbitration clause of the Contract exists; therefore, the instant application is not maintainable.

e) Without prejudice to the statements in the foregoing paragraphs, it is further submitted that the petitioner has manifestly failed to make out any ground for granting an injunction against respondents No. 3 and 4 and thus there is no basis whatsoever for seeking any injunction against the respondents No. 3 and 4.

f) In the above circumstances, it is submitted that the instant application is liable to be summarily rejected with exemplary cost, without prejudice to the rights of the respondents to institute proceeding against the petitioner for realization of damages in respect of grant of injunction on a misconceived application and allegations which are manifestly false. The Hon’ble Court should also consider drawing proceedings against the petitioner for swearing affidavit on the basis of palpably false information and allegations.

- Mr. Ajmalul Hossain, the learned Senior Advocate appearing along with Mr. A.B.M. Siddiqur Rahman on behalf of the petitioner placed the application, supplementary affidavits, other affidavits, provisions of law and also placed written submissions on behalf of the petitioner. The written submissions are reproduced below:

- The instant application under section 7Ka of the arbitration Act, 2001 (“Act”) is filed before this Honourable Court praying an order of injunction upon the Respondents from selling, alienating, disposing of transferring the properties listed in the schedule of the application till award is passed in the pending arbitration proceeding before the Arbitral Tribunal of Singapore International arbitration Centre (SIAC).

- This Honourable Court upon hearing the petitioner rightly issued the interim order as prayed for in accordance with the scheme and provision of the Act.

- The Respondents filed applications for vacating the order of interim order of this Honourable Court.

- During the hearing on that application, this Honourable Court first decided to settle the preliminary issue as to whether under section 3 of the Act, this Court has jurisdiction to deal with the application under section 7ka. The Respondents argue that under section 3 of the Act, as the seat of arbitration is in Singapore, the Act itself has no application and thus this Court has no jurisdiction to entertain the instant 7ka application.

- It is the generally accepted principle in each developed legal system that the state courts order interim and conservatory measures in support of arbitration despite the powers of the arbitral tribunals to do so. There are many reasons: the tribunal may not yet have been composed or it may lack the required power; urgent relief may be required and the tribunal cannot be constituted quickly; an application without respondent may be essential to prevent avoidance of the relief sought.

- Court has power to order interim measures despite arbitration agreement. Article VI(4) of European Convention provides ‘A request for interim measures or measures of conservation addressed to a judicial authority shall not be deemed incompatible with the arbitration agreement, or regarded as a submission of the substance of the case to the court’ (Bahia Industrial SA v. Eintacar-Eimar SA, XVIII YBCA 616 (1991)).

- Similar provisions can be found in a number of arbitration laws. For example, Article 9 Model Law provides that “It is not incompatible with an arbitration agreement for a party to request, before or during arbitral proceedings, from a court an interim measure of protection and for a court to grant such measure.” (See also Greece, International Commercial arbitration Act 1999, Article 9; Germany, ZPO section 1033; Trade Fortune Inc v. Amalgamated Mills Supplies Ltd. (1995) XX YBCA 277 (British Columbia Supreme Court, 25 February 1994)).

- Even in cases where neither the applicable arbitration rules nor the relevant law contain express provisions for interim measures by the courts, judges have in most cases asserted such a power and have assumed a concurrent jurisdiction of state courts and arbitration tribunals in relation to interim measures. For example, French Court de cassation have asserted this kind of authority.

- In the US, courts can order provisional measures in support of arbitration. The third Circuit Court of Appeals in Blumenthal v. Merrill Lynch Pierce, Frenner & Smith Inc., 910 F2d 1049 (2nd Cir 1990); held, “the pro-arbitration policies reflected in the… Supreme Court decisions are furthered, not weakened, by a rule permitting a district court to preserve the meaningfulness of the arbitration through a preliminary injunction. arbitration can become a “hollow formality " if parties are able to alter irreversibly the status quo before the arbitrators are able to render a decision in the dispute. A district court must ensure that the parties get what they bargained for a meaningful arbitration of the dispute…..(See also Daye Nonferrous Metals Company (China) v. Trafigura Beheer BV (Netherlands), XXIII YBCA 984 (1998) (USDC SDNY, 2 July 1997)).

- In India, conflicting decisions are there as to whether the power of the courts to order interim relief also extends to arbitration tribunals having their seat in a different country or whether it is limited to arbitrations having their seat in India. The Supreme Court of India in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA 2002 AIR (SC) 1432 as well as in several decisions of the High Court including Olex Focus Pvt Ltd. v. Skodaexport Cop. Ltd. 2000 AIR (Del) 171 held that court can order interim measures where seat of arbitration is outside India. Bhatia Case was followed in Venture Global Engineering v. Satyam Computer Services Ltd. (2008) 4 SCC 190. There are some decisions having the opposite view. However, the judgment of the Indian Supreme Court dated 08.01.2010 has not overruled Bhatia but Bhatia was distinguished in facts and circumstances.

Under the Act 2001: Bangladesh

- Section 3 of the Act came under scrutiny by this Division on several occasions. The section has been thoroughly analyzed and interpreted in 12 MLR 265. The learned Judge in that case did a long journey to find out the scope of the Act under section 3 in light of the objects of the Act keeping in mind the international commitment and obligations under the New York Convention of which Bangladesh is a signatory and also the provisions of the UNCITRAL Model Law. In this case it is held that under section 3 of the Act the court has jurisdiction to give appropriate relief especially the interim orders where the seat of arbitration is outside Bangladesh.

HRC Shipping Limited v. MV X-Press Manaslu & others; 12 MLR 265

- In reaching the conclusion in relation to the scope of section 3 of the Act, the court looked at the object clause of the Act, which was prepared on the basis of the Model Law on International Commercial arbitration adopted by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) in 1985. Mr. Justice Shamim Hasnain in his judgment discussed in detail the rationale of his finding referring various case laws of different jurisdictions and international instruments and held that “It is evident that section 3(1) provides that 2001 Act would apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. It does not state that it would not apply where the place of arbitration is not in Bangladesh. Neither does it state that the 2001 Act would “only " apply if the place of arbitration is Bangladesh “.. (Para 32).

- The court also held “The provision of section 3(1) of the 2001 Act suggests that the intention of the legislature was to make the 2001 Act compulsorily applicable to arbitration, including an international commercial arbitration that takes place in Bangladesh. Parties cannot by agreement override or exclude the non-derogable provisions of the 2001 Act in such arbitrations. However, section 3(1), does not imply that the provisions of the arbitration Act would not be applicable to arbitration proceedings taking place outside Bangladesh” -(Para 33).

- “It is to be noted that the definition of international commercial arbitration makes no distinction between international commercial arbitration which takes place in Bangladesh or international commercial arbitration which takes place outside Bangladesh, If the proposition of the plaintiff is correct then the provision for enforcement of foreign arbitral award will become redundant as prior to completion of the foreign proceedings, one of the party is free to obtain an order injunction the foreign arbitration proceedings and as such there would not be any foreign arbitral award-to-enforce. Moreover, unless one of the proceedings is stayed, the dispute is open to resolution in multiple forums resulting in multiplicity of proceedings " (Para 46).

- In the above Judgment all the cases of this jurisdiction referred by the Respondents have been discussed.

- It is submitted that giving the narrow meaning of section 3 will be opposed to public policy, for no country lives in isolation from the international community.

- Therefore in light of the above, it is submitted that this Honourable Court should also adopt the finding as referred in HRS Shipping case, 12 MLR 270, and hold that the application of the Petitioner is maintainable.

Procedure in case of disagreement

One further point needs to be addressed in this connection. Already another Bench of this Division has given decision on this issue and that has not been overturned by the Honourable Appellate Division. If this Honourable court has disagreement with that decision then there is a procedure to be followed as laid down in Pubali Bank vs. the Chairman, First Labour Court, Dhaka and another; 12 BLD (AD)72. The Honourable Appellate Division in paragraph No. 6 held that ‘…..If a Single Bench intends to differ from the decision from another Single Bench or if a Division Bench wants to differ from the decision of another Division Bench then the matter should be referred to the Chief Justice for constituting an appropriate Bench for resolving the dispute…..

- Apart from the aforesaid written submissions, Mr. Hossain referred to certain sections from “Comparative International Commercial Arbitration” by Julian D M Lew QC, the cases of Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation vs. Amgen, Inc, 882 F.2d 806, Stephen Blumenthal and Les Fein vs. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, 910 F.2d 1049, an article by Lalit Bhasin titled “The Grant of Interim Relief Under the Indian arbitration Act of 1996”, an article by Dr. Abhishek M. Singhvi titled “Interim Relief: The Role of arbitration and the Court in India”, an article by D. Dave titled “Availability of Interim Relief in Respect of International Arbitration”, an article by Lira Goswami titled “Interim relief’s: The Role of the Courts”, a manual by J. Savage titled “Provisional and Conservatory Measures in the Course of the arbitration Proceedings (Part 4 Chapter III), the case of HRC Shipping Limited vs. M.V. X-Press Manaslu and others 12 MLR(HC) 2007, the cases of Bhatia International vs. Bulk Trading S.A. and another AIR 2002(SC)1432, Venture Global Engineering vs. Satyam Computer Services Ltd. and another 4 SCC (2008)190 and Venture Engineering vs. Satyam Computer Services Ltd., a judgment passed by the Indian Supreme Court in SLB (civil) No. 9 of 2010.

- Apart from the written submissions, the learned Advocate relied upon the provisions as laid down in the Act of 2001 and submitted that from a plain reading of different sections along with section 7ka and 2(c) it appears that this Court is competent to pass an interim order of injunction to protect the right of the parties in arbitration. Since there is no specific provision excluding application of the Act of 2001 to arbitration held outside Bangladesh, it cannot be said that this Court has no jurisdiction to entertain an application for injunction in relation to a foreign arbitration. Relying upon the decision in the HRC case he submits that in passing the judgment the single Bench elaborately discussed all the cases relating to section 3 of the Act of 2001 and came to a conclusion that in view of the decision passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case and the provisions of the UNCITRAL Model Law of International Commercial arbitration, the power and jurisdiction of the Court in Bangladesh cannot be ousted even if the place of arbitration is outside Bangladesh. Regarding the position of the respondents No. 3 and 4 he submits that being a director of the respondent company or sister concern thereof they have relations with the transaction in question and as such their property can be attached for ends of justice. He submits that the said respondents cannot avoid their liability by taking the plea of the main respondent, rather the respondents are under legal obligation to contest the arbitration proceeding and the petitioner has a legitimate expectation to get interim relief till disposal of the arbitration proceeding. He submits that since section 10 of the Act of 2001 is applicable in a foreign arbitration, as decided by this Court in the HRC case, an order under section 7ka of the said Act can also be granted in any foreign arbitration, including the arbitration in the present case.

- Dr. Sharif Bhuiyan, the learned Advocate appearing, along with Mr. Tanim Hussain Shawon, Advocate, on behalf of the respondents No. 3 and 4 opposes the application. The learned Advocate placed the affidavit in opposition and provisions of law. Dr. Bhuiyan also submitted written arguments which run as follows:

SUB-SECTIONS (1) AND (2) OF SECTION 3 OF THE arbitration ACT, 2001 (THE “ACT”) MUST BE READ TOGETHER

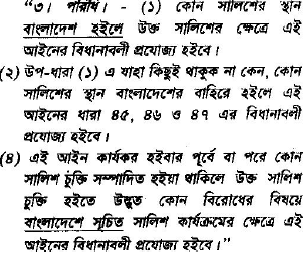

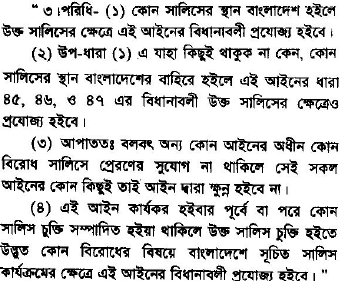

1. Section 3 of the Act provides as follows:

(emphasis added)

- Sub-sections (1) and (2) of Section 3, when read in conjunction, make it clear that in respect of arbitrations held outside Bangladesh no provisions of the Act, other than Sections 45, 46 and 47, are applicable.

SECTION 7KA SHOULD BE READ IN THE CONTEXT OF SECTION 3

- The petitioner has sought to argue that since Section 7Ka empowers the High Court Division to order interim measures in respect of international commercial arbitrations, such orders can be made in respect of any international commercial arbitration irrespective of the place of arbitration. This reading of Section 7Ka makes Section 3 of the Act redundant, and thus is contrary to the well-established principle of statutory interpretation that a construction which leaves without effect any part of the statute will be rejected (Maxwell on Interpretation of Statutes, 12th ed., by P. St. J. Langan, 1976, p. 36, and Interpretation of Statutes and Documents, by Mahmudul Islam, 2009, p. 76).

- The petitioner has sought to read Section 7Ka of the Act to the entire exclusion of Section 3, which is contrary to the well-established principle of statutory interpretation that a statute must be read as a whole. According to this principle, every provision of a statute has to be construed with reference to the context and other provisions thereof (Maxwell on Interpretation of Statutes, 12th ed., by P. St. J. Langan, 1976, pp. 47, 58-64, and Interpretation of Statutes and Documents, by Mahmudul Islam, 2009, pp. 307-308).

- The petitioner has also sought to argue that since Sub-section (1) of Section 3 provides that the Act shall apply to arbitrations in Bangladesh and does not expressly provide that the Act shall not apply if the place of arbitration is outside Bangladesh, Section 7Ka would apply even if the place of arbitration is outside Bangladesh. Such an interpretation is flawed because Section 1(2) of the Act provides that the Act extends to the whole of Bangladesh; therefore, Sub-section (I) and sub-section (2) of Section 3 would be superfluous if the petitioner’s interpretation were correct.

- Sub-section (2) of Section 3 makes it abundantly clear that subsection (1) of Section 3 not only provides that the Act would apply if the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh, but also excludes the applicability of the Act in respect of arbitrations outside Bangladesh, with the exceptions of Sections 45, 46 and 47 of the Act.

DECISIONS BY THE APPELLATE DIVISION AND THE HIGH COURT DIVISION OF BANGLADESH SUPREME COURT

- In Unicol Bangladesh v. Maxwell 56 DLR (AD) (2004) p. 166, at p. 172 the Appellate Division observed that due to Sections 3(1) and 3(4) of the Act the power of the Court for granting an order of injunction is limited in application to arbitrations being held in Bangladesh.

- In Uzbekistan Airways v. Air Spain Limited, 10 BLC (2005) p. 614, at p. 616 (para 5), it was held as follows:

In the course of hearing we had drawn attention of Mr. Nabi to the decision reported in 56 DLR (AD) 166 and the unreported decision of Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal Nos. 73-75/1982 and the case reported in 54 DLR 93 and 9 BLC 96, In these decisions both the Divisions of this Court had the opportunity to examine the scope of Section 10 of the Act and on a careful scrutiny of the scheme and the relevant provisions of the Act, both the Divisions have taken the view that Section 10 of the Act has no manner of application with regard to foreign arbitral proceeding though the foreign arbitral award can be enforced in this country pursuant to the provisions of Section 3(2) read with Sections 45-47 of the Act. In view of the matter it appears that the scope of Section 10 of the Act is well-settled and it has been decided more than once by the Appellate Division in the aforesaid two cases that Section 10 of the Act does not apply to foreign arbitral proceedings.

- In Canda Shipping v. TT Katikaayu, 54 DLR (2002) p. 93, at p. 94 (para 7) it was held as follows:

I have considered the submissions of the learned Advocates of both sides. From a reading of Section 3(1) and (2) it appears to me that the Act applies to arbitration where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh and not in a foreign country. Sections 45, 46 and 47 are made exceptions to section 3. These sections deal with foreign arbitration Award and not with foreign arbitration proceeding. It means that once an arbitration proceeding in a foreign country is completed, the arbitral award, on an application by any party will be enforced by execution by a court, of this country under the Civil Procedure Code, in the same manner as if it were a decree of the court. But in the instant case the petitioner has come to stay the proceeding before this court on the ground that an arbitration proceeding has been initiated in London and not to enforce any award given in a foreign arbitration so, in my view, section 10 of this Act is not applicable and the application to stay the proceeding before this court could not be entertained considering the facts that it involves arbitration proceeding in a foreign country and not in Bangladesh and the application is not concerning an arbitration award but concerning an arbitration proceeding.

- In support of their contention the petitioner relies on HRC shipping Limited v. M.V. X-Press Manaslu 12 MLR (HC) (2007), p. 265. The judgment in this case heavily relied on the judgment of the Indian Supreme Court in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. 2002 AIR (SC) 143, (2002) 4 SCC 105. However, in a most recent judgment of the Indian Supreme Court in Dozco India P. Ltd. v. Doosan Infracore Co. Ltd. 2010 (9) UJ 4521 (SC): Manu/SC/0812/2010 (decided on 8 October 2010), the decision in the Bhatia Case has been distinguished in respect of arbitration clauses which expressly provide that the place of arbitration would be outside India (as has been provided in the instant case). In the Dozco Case, the arbitration clause provided that disputes between the parties would be finally settled by arbitration in Seoul, Korea. It was held in the Dozco Case as follows:

That is exactly the case here. The language of Article 23.1 clearly suggests that all the three laws are the laws of The Republic of Korea with the seat of the arbitration in Seoul, Korea and the arbitration to be conducted in accordance with the rules of International Chamber of Commerce. In respect of the bracketed portion, however, it is to be seen that it was observed in that case:…It seems clear that the submissions advanced below confused the legal “seat” etc. of an arbitration with the geographically convenient place or places for holding hearings. This distinction is nowadays a common feature of international arbitrations and is helpfully explained in Redfern and Hunter in the following passage under the heading

“The Place of arbitration:

The preceding discussion has been on the basis that there is only one “place” of arbitration. This will be the place chosen by or on behalf of the parties; and it will be designated in the arbitration agreement or the terms of reference or the minutes of proceedings or in some other way as the place or “seat” of the arbitration. This does not mean, however, that the arbitral tribunal must hold all its meetings or hearings at the place of arbitration. International commercial arbitration often involves people of many different nationalities, from many different countries. In these circumstances, it is by no means unusual for an arbitral tribunal to hold meetings-or even hearings-in a place other than the designated place of arbitration, either for its own convenience or for the convenience of the parties or their witnesses….

It may be more convenient for an arbitral tribunal sitting in one country to conduct a hearing in another country-for instance, for the purpose of taking evidence…..In such circumstances, each move of the arbitral tribunal does not of itself mean that the seat of the arbitration changes. The seat of the arbitration remains the place initially agreed by or on behalf of the parties.

These aspects need to be borne in mind when one comes to the Judge’s construction of this policy.

It would be clear from this that the bracketed portion in the Article was not for deciding upon the seat of the arbitration, but for the convenience of the parties in case they find to hold the arbitration proceedings somewhere else than Seoul, Korea. The part which has been quoted above from the decision in Naviera Amozonica Peruana S.A. v. Compania Internationacional De Seguros Del Peru (cited supra) supports this inference. In that view, my inferences are that:

- a clear language of Articles 22 and 23 of the Distributorship Agreement between the parties in this case spell out a clear agreement between the parties excluding Part I of the Act.

- the law laid down in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. and Anr. (cited supra) and Indtel Technical Services Private Ltd. v. W.S. Atkins Rail Ltd. (cited supra), as also in Citation Infowares Ltd. v. Equinox Corporation (cited supra) is not applicable to the present case.

3. Since the interpretation of Article 23.1 suggests that the law governing the arbitration will be Korean law and the seat of arbitration will be Seoul in Korea, there will be no question of applicability of Section 11(6) of the Act and the appointment of Arbitrator in terms of that provision.

(emphasis added)

- The petitioner has sought to argue that as a matter of policy interim orders should be passed even in respect of arbitration proceedings outside Bangladesh. It is submitted that whatever may be the merit of such policy, in view of the express provisions of the Act, the Courts are not empowered to order interim measures in respect of arbitrations taking place outside Bangladesh. In this regard. His Lordship Mr. Justice A.B.M. Khairul Haque in the case of M/s. Stratus Construction Company v. Government of Bangladesh 22 BLD (HCD) 2002 236 held as follows:

- It should be remembered that it is for the legislatures to enact laws to cater the needs of the people at large providing for rights and remedies and obligations of the litigant public and a Court of law shall only uphold those laws if necessary, by propounding and explaining the provisions as and when necessary in given circumstances, but it cannot create new right or remedy or give itself a jurisdiction which is not given in the Act itself.

- In this connection it would be profitable to repeat what Lord Loreburn L.C. said in the case of Vickers, sons of Maxim Limited vs. Evans 1910 AC 444:

My Lords, this appeal may serve to remind us of a truth sometimes forgotten, that this House sitting judicially does not sit for the purpose of hearing appeals against Acts of Parliament, or of providing by judicial construction what ought to he in the Act, but simply of construing what the Act says. We are considering here not what the Act ought to have said, but what it does say…

The purpose of arbitration is to settle the disputes, specially the commercial disputes, promptly. So that the litigant business men can move on with their commercial pursuits to their own benefit as well as of the country as a whole, instead of spoiling their efforts in dragging on in fruitless and sometimes in circuitous litigations, causing loss to their business efforts leading to the ultimate national waste.

- The United Nations Commission on International Commercial arbitration prepared certain model laws known as UNCITRAL Model Law. The Shalish Ain, 2001, repealing the earlier arbitration Act, 1940, is prepared on that model The whole purpose of the new enactment is that the arbitration proceeding may proceed with minimum interference from Court, unless it is a question of jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal.

- Earlier the arbitration Act, 1940 in its Section 42 provided for application of the Code of Civil Procedure, which obviously includes the power to issue an order of injunction. The Salish Ain, 2001, does not contain such a provision. It would rather appear that such a provision was consciously omitted. The purpose, as it appears, is clear, to push ahead arbitral proceeding without any hindrance.

- However, provisions for interim relief can always be enacted if it is felt so necessary in the interest of the people at large, but till such provisions are enacted, the High Court Division, would not have any power to issue any order of injunction, temporary or otherwise.”

(emphasis added)

COURT’S POWER OF INTERIM ORDER MAY EXTEND TO FOREIGN arbitration PROCEEDING ONLY IF EXPRESSLY PROVIDED BY

STATUTE

- Court’s power of interim order may extend to foreign arbitration proceeding only if expressly provided by statute, as is evident from the UNCITRAL Model Law (Article 1(2) read with Article 9), English arbitration Act, 1996 (Section 2(3)(b) read with Section 44(2)(c)) and Singapore International arbitration Act, 1994 (Section 5(2)(b)(i)).

- The above submissions of the respondents no. 3 and 4 are without prejudice to their other submissions, including, the submission that an order under Section 7Ka cannot be issued against individuals who are not parties to the arbitration proceeding in support of which the instant application has been filed.

- Dr. Bhuiyan also referred to certain sections from “Maxwell on Interpretation of Statute” by P. St. J. Langan, and “Interpretation of Statutes and Documents” by Mr. Mahmudul Islam and also referred to several decisions and also referred to UNCITRAL Model Law, English arbitration Act of 1996 as well as Singapore International arbitration Act of 1994. Dr. Bhuiyan also relied upon the Bhatia case as referred to by the learned Advocate for the petitioner. Dr. Bhuiyan submits that it is the duty of the Court of law to interprete the law as per the wording as prescribed in the statute and in the present case the statute is very clear and no ambiguity exists. He further submits that the Courts of our jurisdiction have consistently held that the powers of this Court under the Act of 2001 are limited in respect of foreign arbitration to those set out in Sections 45, 46 and 47 of the Act of 2001.

- He also submits that it is apparent from the documents relied on by the petitioner that the respondents No. 3 and 4 are not parties to either the agreement in question or the arbitration proceeding in any manner, which has also been admitted by the arbitrator in a communication; as such, there is no scope to attach the property of a third party.

- By referring to the decisions of our Court as well as Indian jurisdiction, the learned Advocate submits that if the arguments of the Bhatia case and the Dozco case are taken into consideration, it would appear that in the present case the parties expressly excluded the jurisdiction and applicability of the Act of 2001 by agreeing to Singapore as the place of arbitration. Dr. Bhuiyan referred to the arbitration clause in Annexure-B to the application and placed the same side by side with the arbitration clause as referred to in the Dozco case and submits that both clauses are similar in nature and that accordingly present application is not maintainable.

- I have perused the application under section 7ka of the arbitration Act of 2001, supplementary affidavits, affidavits in opposition, written arguments, materials placed before this Court, decisions as referred to and provisions of law and heard the learned Advocates for the contesting parties.

- On perusal of the same it appears that in the case in hand the parties entered into a contact for supply of goods and in the said contact/agreement a clause namely “arbitration” clause was incorporated. Ultimately the contact was terminated, and as a result, the petitioner initiated arbitration process by invoking the arbitration clause as incorporated in the said agreement. Pursuant to the arbitration clause the petitioner, a company incorporated in Korea proceeded in Singapore because of the specific jurisdiction specified in the said arbitration clause. Thereafter, the tribunal has been proceeding in accordance with the relevant law, Rules/Regulations etc. Pending arbitration process, the petitioner invoked Section 7ka of the arbitration Act of 2001 and filed the application before this Court for an order of injunction over certain properties mentioned in the schedules of the application owned by the respondents No. 3 and 4. This Court admitted the application and passed interim order.

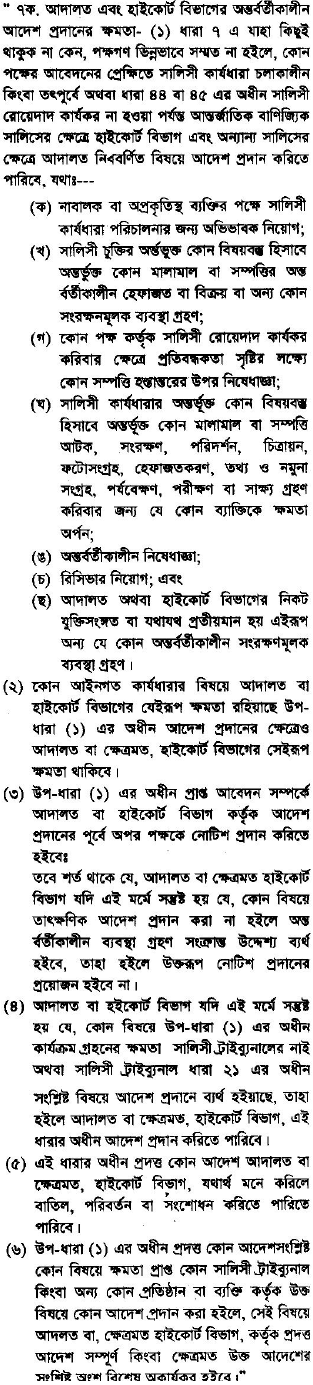

- It appears that the Act of 2001 was enacted in 2001 for the purpose stated in the preamble of the said Act. The paramount question raised in the instant application is whether the provision of section 7ka as inserted in the said Act of 2001 in 2004 by an amendment is applicable to foreign arbitrations. On perusal of the said provision of law it appears that notwithstanding anything contained in section 7 of the Act of 2001, on an application made by the parties, this Court can pass an interim order for ends of justice so far it relates to International Commercial arbitration. Section 7ka of the Act of 2001 reads as follows:

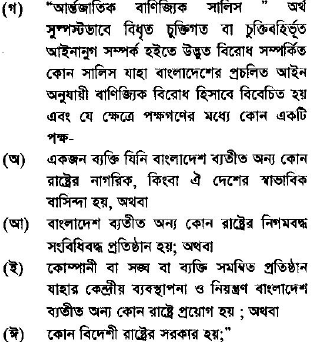

Section 2(ga) of the Act of 2001 provides as follows:

- So, it appears that “International Commercial Arbitration” means an arbitration, wherein a foreign party is involved in the manner stated in section 2(ga).

- Section 3 of the Act of 2001 runs as follows;

- Section 3 consists of 4(four) subsections. In sub-section (1), it has been categorically stipulated that the provision of the Act of 2001 shall apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. Sub-section (2) deals with the enforcement of foreign arbitration awards in the manner that notwithstanding anything contain in subsection (1), in case of enforcement of award passed in a foreign arbitration, sections 45, 46 and 47 of the Act of 2001 can be invoked. Sub-section (4) stipulates that the provisions of the Act shall apply to the arbitration proceeding in Bangladesh arising out of arbitration agreement concluded prior or subsequent to the coming into force of the Act of 2001. So, on a plain reading of section 3 of the Act, it is very much apparent that the Act of 2001 shall only apply when the place of arbitration or the arbitration proceeding is in Bangladesh.

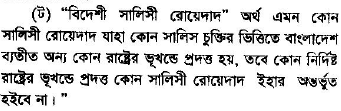

- The provision as laid down under section 3(2) of the Act affirmed such exclusion by specific manner wherein the legislature categorically stated where and under what circumstances the Act shall apply when the place/proceeding is not in Bangladesh. The intention of the legislature is that the award in the foreign arbitration can be enforced in Bangladesh, as provided in sections 45, 46 and 47 of the Act. It means that by section 3(2) of the Act the legislature specifically excluded the application of this law, apart from sections 45, 46 and 47, to an arbitration proceeding, the place of which is outside Bangladesh, or in other words, a foreign arbitration. Though, definition of foreign arbitration is not available in the said Act, it appears that section 2(ta) of the said Act deals with the definition of foreign arbitration award, which runs as follows:

- On perusal of the definition, it appears that foreign arbitration award means an award made in the territory of any country other than Bangladesh. So from a combined reading of section 2(ga), 2(ta) and section 3 of the Act, it is apparent that the intention of the legislature is that the scope of the Act of 2001 is limited within the territory of Bangladesh, except that there is a scope to enforce an award passed in a foreign arbitration, pursuant to section 3(2) read with sections 45, 46 and 47 of the said Act of 2001.

- Modern method adopted by the courts is literal construction of statutes conditioned by what is called the golden rule of construction. Generally all statutes are to be construed according to the plain, literal and grammatical meaning of the words and one should not import words into an enactment which are not therein. When words in a statute are clear and unambiguous they should be construed according to their tenor and meaning for that reflects the intent and purpose of a legislation. It is only where the meaning is incomplete or ambiguous, it is possible to construe it in a way to remove absurdity so as to give effect to the purpose of a legislation. Where literal meaning of the words used in a statute is unambiguous and clearly conveys a reasonable meaning, the court has no power to read into the statute words for conveying a different meaning. The rule of literal construction requires the court to construe a provision of a statute according to the ordinary and natural meaning of the language used by the legislature as the language so applied best declares the intention of the legislature and recourse to any other principle of interpretation is unnecessary.

- So it appears that in the case in hand, there is no ambiguity available in the provision laid down in section 3 of the Act of 2001.

- However, it has been argued by the petitioner that while deciding the case of HRC Shipping Limited vs. M.V. X-Press Manaslu and others, reported in 12 MLR (2007) 265, this Court, considering all aspects of the Act of 2001 as well as international conventions relating to arbitration specially the Model Law and lastly the decision passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia Case, came to a conclusion that the provisions of the Act of 2001 is also applicable to a foreign arbitration. On perusal of the judgment as referred herein it appears that his Lordship considered a series of judgments passed by this Court as well as our Apex Court regarding the applicability of the Act of 2001 to a foreign arbitration but his Lordship considered the Model Law, the international conventions and the very spirit and intention of the purpose of amendment of the Act of 2001 and certain decisions of Indian jurisdiction, which include the case of Bhatia International-Vs-Bulk Trading S.A. and another reported in AIR 2002 (SC) 1432 and came to a conclusion that since the legislature did not mention anything excluding the jurisdiction relating to foreign arbitration, the provision of Act of 2001 is also applicable to a foreign arbitration. Thus, his Lordship, exercising the power conferred under section 10 of the Act of 2001, stayed proceeding relating to a foreign arbitration. Admittedly the aforesaid decision has not been challenged before the Apex Court, and on a plain reading of the same it appears that the same is an exhaustive one.

- It has been-mentioned earlier that the contention as asserted by the learned Judge depends upon the Model Law of International arbitration, the purpose of enactment of the Act of 2001, namely the proper application of alternative dispute resolution etc., and in a lengthy judgment his Lordship came to a conclusion that, despite the language incorporated in section 3 of the Act and despite several decisions passed by this Court regarding the applicability of the Act to foreign arbitration the provisions of the Act of 2001 can be applicable to a foreign arbitration under the facts and circumstances stated therein.

- It appears that in the said case the Court relied upon the Bhatia case as mentioned hereinabove. On perusal of the judgment passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case it appears that the Indian Supreme Court considered the provision of the interpretation of statute, the intention of the legislature, the consequence of law, the ambit, scope and the reasons behind enacting the arbitration Act of 1996 and the Indian Supreme Court came to a conclusion that on the plain reading of section 2, which is similar to our section 3, since the legislature by express provision did not oust the application of the Act to a foreign arbitration, it cannot be said that the Indian arbitration Act is not applicable to a foreign arbitration. However, in the said case, Indian Supreme Court came to a conclusion that if the parties by express or implied manner did not exclude the jurisdiction in that case the provisions of the Indian Act shall apply.

- It appears that the same point was raised before the Indian Supreme Court once again in the case of Dozco India P. Ltd. vs. Doosan Infracore Co. Ltd. in arbitration Petition No. 05 of 2008, wherein the single Judge accepted the decision of the Indian Supreme Court in interpreting the Indian arbitration Act of 1996 in such a manner as to provide application to a foreign arbitration unless the parties either in express or implied manner excluded the same. On perusal of the Dozco case, it appears that considering Articles 22 and 23 of the arbitration agreement in question in the Dozco case the court came to a conclusion that since by express manner the parties excluded the jurisdiction, the provision of Act of 1996 shall not be applicable in that particular case.

- From a combined reading of the judgments passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case and the Dozco case as well as the HRC case, there is no room to have any doubt about the application of the Act of 2001 to a foreign arbitration. Apart from that, on perusal of the judgment passed by the Indian Supreme Court in the case of Venture Global Engineering vs. Satyam Computer Services Ltd. and another reported in 4 SCC (2008) 190, it appears that in that case also the Court accepted the principle laid down in the Bhatia case and came to a conclusion that part-I of the Act of 1996 is applicable to International Commercial arbitration held outside India, unless the same has been excluded by an agreement between the parties. Therefore, unless applicability of any provision has been excluded specifically, the parties can invoke the provision of the Indian arbitration Act of 1996.

- Furthermore, the Model Law and the arbitration law of Singapore adopted the provision of interim measures in clear language. The English arbitration Act of 1996 also makes express provision for passing interim order by the local courts in relation to a foreign arbitration where the place is beyond the local jurisdiction.

- Admittedly, while enacting the Act of 2001 our legislature followed the Model Law and the recommendations made by different authorities, but it is the parliament which is to enact the law and the parliament enjoys ample power either to accept any recommendation of Model Law in full or in part. On perusal of section 3 of the Act of 2001, there is no doubt about the language of the said provision wherein section 3(1) and section 3(4) of the Act of 2001 categorically mention about the applicability of the Act where the place of the of arbitration proceeding is in Bangladesh. However, it is a practice to adopt or follow the precedent and the decisions in interpretation of law or application thereof, but such practice can only be permitted where there is a room for interpretation in case of any ambiguity and a Court of law cannot sit over the mind of the legislature but can only explain and interpreted the law enacted by the Parliament. In numerous decisions, this Court as well as of our Apex Court came to a conclusion that unless or until the Parliament amended the law or a person can show that any provision of law is ultra vires the Constitution of the Republic, this Court cannot strike down or interpret a specific law in a different manner.

- It appears that the question of applicability of the Act of 2001, came before this Court as well as our Appellate Division on several occasions. Though in a different context or under different facts and circumstances, but the question of applicability was raised in the case of Unicol Bangladesh Blocks Thirteen and Fourteen and another Vs. Maxwell Engineering Works Ltd. and another reported in 56 DLR (AD) 166, wherein their Lordships of our Apex Court in paragraph 3 stated that; “It may be mentioned the venue of the arbitration was in Singapore.”

- Thereafter their Lordships in paragraph 11 held as follows:

The learned Counsel for the appellants upon referring to the provision of sections 3(3) and 7 of Act 1 of 2001, hereinafter referred to as the Act, has submitted as the said provisions shall govern the proceeding (the suit) in question and, as such, the order of injunction passed by the trial Court and upheld by the High Court Division restraining the Arbitrators from proceeding with the arbitration already initiated is not sustainable in law in view of the provision of section 10(3) of the Act. The learned Counsel also submitted that because of the provision of section 20(4) of the Act the High Court Division as well as the trial Court were in serious error in granting temporary injunction.

- Their Lordships in paragraph 13 further held as follows:

The learned counsel entering caveat for the respondent No. 1 submitted that in view of the provision of section 3(1) of the Act, the provision of the Act is applicable only in the case of arbitration which is being held in Bangladesh and as the arbitration in question is not being held in Bangladesh provisions as in sections 7, 10 and 20 of the Act have no manner of application as regard the proceeding initiated by the respondent No. 1.

- Their Lordships further held in paragraph 15 as follows;

..The other contention that because of the provision of sections 45-47 of the Act award, if any, made in foreign country would very much be enforceable in Bangladesh can all together be considered correct in view of the provision in the Explanation 3(b) of section 44A of the Code of Civil Procedure. In view of the provision of section 2(g) and section 3(1) and 3(4) of the Act of 2001 the contention of the learned Counsel as to maintainability of the suit because of the provisions in sections 7, 10 and 20 of the Act is not legally well founded.

- Their Lordships also held in the same paragraph as follows:

In assailing the findings and decisions of the High Court Division and the trial Court relating to the matter that weighed with the Courts, the learned Counsel has submitted that the courts being totally oblivious of the provision of the Act were in error in considering the matter of injunction in the background of the aspect that generally weighs with the Court in considering the matter of temporary injunction and granting an order of temporary injunction cannot be considered well founded since we have already mentioned that the law as in sections 3(1) and 3(4) of the Act barring the Court from granting an order of injunction is limited in application as to the arbitration being held in Bangladesh, but not as to matter restraining a particular party form proceeding with arbitration in foreign country in respect of a contract signed in Bangladesh.

- So it appears that their Lordships in a clear language stated that the Appellate Division already mentioned that the law as per section 3(1) and section 3(4) of the Act barring the Court from granting an order of injunction is limited and applicable to the arbitration being held in Bangladesh but not as to matter restraining a particular party from proceeding in an arbitration in a foreign country in respect of foreign contact signed in Bangladesh. So by this language their Lordships clearly explained and interpreted the provision of section 3 of the Act of 2001. Similarly, in a civil jurisdiction, another Division Bench of this Court in the case of Uzbekistan Airways vs. Air Spain Ltd. reported in 10 BLC (2005) 614 held, in paragraph 5, as follows:

We have carefully scrutinised all the grounds and the submissions made by the learned Advocate for the appellants and, to the best of our ability, have examined the relevant provisions of the law and after studying the law we find that the view taken by the courts below are in accordance with law. Here it may further be mentioned that the question mooted by Mr. Nabi had already been considered by both the Divisions of this Court on more than one occasion and both the Divisions consistently held that section 10 of the Act is not applicable to arbitral proceeding in a foreign country and section 3(2) simply lays down the provision that a foreign arbitration award is enforceable within Bangladesh. The courts below also reflected the principles laid down by both the Divisions of this Court in the impugned order. In the course of hearing we had drawn attention of Mr. Nabi to the decision reported in 56 DLR (AD) 166 and the unreported decision of Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal Nos. 73-75/1982 and the case reported in 54 DLR 93 and 9 BLC 96. In these decisions both the Divisions of this court had the opportunity to examine the scope of section 10 of the Act and on a careful scrutiny of the scheme and the relevant provisions of the Act both the Divisions have taken the view that section 10 of the Act has no manner of application with regard to foreign arbitral proceeding though the foreign arbitral award can be enforced in this country pursuant to the provisions of section 3(2) read with sections 45-47 of the act. In that view of the matter, it appears that the scope of section 10 of the Act is well settled and it has been decided more that once by the Appellate Division in the aforesaid two cases that section 10 of the Act does not apply to foreign arbitral proceedings. Therefore, it appears to us that the courts below did not commit any error of law in rejecting the application filed by the appellant as petitioner before the trial Court.

- The Court also relied upon the decision reported in 56 DLR(AD) 160 as well as un-reported decision of their Lordships of our Appellate Division and the decision reported in 54 DLR 93 and 9 BLC 96. In this case, the court came to a conclusion, while examining the scope of section 10 of the Act, that section 10 of the Act has no manner of application in respect of foreign arbitration, and only the award of a foreign arbitration can be enforced. It appears that in the case of Canda Shipping and Trading SA vs. TT Katikaayu and another reported in 54 DLR (2002) 93 the High Court Division held as follows:

I have considered the submissions of learned Advocates of both sides: From a reading of section 3(1) and (2) it appears to me that the Act applies to arbitration where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh and not in a foreign country. Sections 45, 46 and 47 are made exceptions to section 3. These sections deal with foreign arbitration Award and not with foreign arbitration proceeding. It means that once an arbitration proceeding in a foreign country is completed the arbitral award, on an application by any party, will be enforced by execution by a court, of this country under the Civil Procedure Code, in the same manner as if it were a decree of the court. But in the instant case the petitioner has come to stay the proceeding before this court on the ground that an arbitration proceeding has been initiated in London and not to enforce any award given in a foreign arbitration. So, in my view, section 10 of this Act is not applicable and the application to stay the proceeding before this court should not be entertained considering the facts that it involves arbitration proceeding in a foreign country and not in Bangladesh and the application is not concerning an arbitration award but concerning an arbitration proceeding.

- So it appears that it has been consistently held by this Court as well as our Appellate Division that section 10 is restricted to arbitration in Bangladesh. Also it appears that in the decision reported in 22 BLD (HC) 236, his Lordships held as follows:

Earlier the arbitration Act, 1940, in its Section 41 provided for application of the Code of Civil Procedure, which obviously includes the power to issue an order of injunction. The Salish Ain, 2001, does not contain such a provision. It would rather appear that such a provision was consciously omitted. The purpose, as it appears, is clear, to push ahead the arbitral proceeding without any hindrance.

- However, provisions for interim relief can always be enacted if it is felt so necessary in the interest of the people at large but till such provisions are enacted, the High Court Division, would not have any power to issue any order of injunction, temporary or otherwise.

- In the above decision, their Lordship expressed their anxiety about the nonexistence of any clause for passing interim measures and at that time section 7ka was not incorporated but the question in the case in hand relates to the application of injunction in relation to a foreign arbitration. Admittedly, UNCITRAL Model Law, English arbitration Act etc. provide for interim measures by the Courts in a foreign arbitration but unless and until the same has been enacted in the Act of 2001 by the Parliament it cannot be said that this Court is bound to follow the said provisions as laid down in the Model Law and laws of jurisdictions other than Bangladesh. It is well settled that if our Apex Court came to a conclusion or interpretation in respect of anything which is different from the decision of the Apex Court of a different country, there is no scope to consider or adopt such decision of different country bypassing the decision passed by our Apex Court.

- It appears that an appeal was preferred against the decision passed by the High Court Division reported in 10 BLC in the case of Uzbekistan Airways vs. Air Spain Ltd., being Civil Petition for Leave Appeal No. 1112 of 2005, wherein the full Bench after hearing the parties vide judgment dated 3.9.2007 held as follows:

…But as the arbitration was to be initiated in foreign country the suit was filed and thereupon the defendants filed an application under section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 for staying the proceedings of the suit and to direct the plaintiff to refer the matter to the arbitration. The application so filed under section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 was opposed by the plaintiff since the place of arbitration is in foreign country and that provision of section 10 has no manner of application as regard the foreign arbitration proceeding.

The application filed under section 10 of the arbitration Act was rejected by the trial Court and thereupon the defendants moved the Court of District Judge under section 115 (2) of the Code of Civil procedure and the said Court upon hearing the parties rejected the revisional application by the order dated April 2, 2005 and thereupon the First Miscellaneous Appeal was filed.

The High Court Division upon hearing the learned Advocate for the appellants and in the background of the provision of law as in sections 3(2) and 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 observed, “We have carefully scrutinized all the grounds and the submissions made by the learned Advocate for the appellants and to the best of our ability have examined the relevant provisions of the law and after studying the law we find that the view taken by the Courts below are in accordance with law”. The High Court Division further observed that it has already been held by both the Divisions of the Supreme Court “that section 10 of the act is not applicable to arbitral proceeding in a foreign country and section 3 (2) simply lays down the provision that a foreign arbitration award is enforceable within Bangladesh”. The High Court Division further observed “that section 10 of the Act has no manner of application with regard to foreign arbitral proceeding though the foreign arbitral award can be enforced in this country pursuant to the provisions of section 3(2) read with sections 45-47 of the Act. In that view of the matter it appears that the scope of section 10 of the Act is well settled and it has been decided more than once by the Appellate Division in the aforesaid two cases that section 10 of the Act does not apply to foreign arbitral proceedings " (56 DLR (AD) 166 and C.P. Nos. 73-75/1987) and thereupon observed that the Courts below i.e. the revisional Court i.e. the Court of District Judge and the trial Court “did not commit any error of law in rejecting the application filed by the appellants as petitioners before the trial Court.

(Underline added).

- So it appears that our Apex Court in a clear language came to a conclusion about the applicability and scope of section 10 of the Act of 2001 and came to a conclusion that section 10 of the Act does not apply to the arbitration proceeding outside Bangladesh. Article 111 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh categorically stipulates that any law declared by the Appellate Division is not only binding upon the High Court Division but binding upon all irrespective of anything. So it appears that not only in one case but in a series of cases this Court and our Apex Court, time and again, came to a conclusion that provision of the Act of 2001 is not applicable to a foreign arbitration except as provided in section 3(2) of the Act itself.

- It has been vehemently argued by Mr. Hossain with reference to the decision in 12 BLD (AD) 72 that once a Bench of this Court has given a decision on an issue, another Bench of this Court cannot differ on such settled issue, rather can refer the matter to a larger bench for resolving the issue in dispute.

- I have full respect to his Lordship for the decision as reported in 12 BLD (AD) 72. But at the same time, when it is clearly found that the judgment passed by the single judge is not based upon the decision of our Apex Court on the particular point, it cannot be said the same issue is being addressed in a proper manner and any decision in violation of the judgment passed by the Appellate Division cannot be a basis of anything, even cannot be basis to refer the matter for a larger bench. Admittedly, in the HRC case, the High Court Division considered all the international conventions and Indian cases, but it appears from the said judgment that the decisions of our Appellate Division have not been considered or reflected in a proper manner. As per Article 111 of the Constitution, there is no scope for this Division to go beyond the dictum as laid down by their Lordships in the Appellate Division unless and otherwise their Lordships reviewed their own decision.

- Apart from that, it appears that for the sake of argument if we accepted the contention as laid down by the Indian Supreme Court in the Bhatia case as well as the Dozco case, it is clear that if the parties expressly or impliedly excluded jurisdiction, in that case the principle of application of the domestic law shall not apply to foreign arbitration. On perusal of the judgment passed in the Dozco case it appears that the Indian Supreme Court, while dealing with the case, referred the arbitration clause namely Article 22 and 23 of the agreement in question and came to a conclusion that since the parties excluded jurisdiction by express wording, the interpretation of Bhatia case was not applicable. In the case in hand, the arbitration clause runs as follows:

Article 5, Governing Law & arbitration The Contract shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of Singapore. All dispute controversies or differences which may arise between the parties, out of or in relation to or in connection with the Contract, or for the breach thereof, shall be finally settled by arbitration in Singapore in accordance with Commercial arbitration Rules of the Singaporean Commercial arbitration Board and under the Laws Singapore. The award rendered by the arbitrator(s) shall be final and binding upon both parties concerned.

- So, it appears that, like the Dozco Case, in the case in hand also, the parties excluded the jurisdiction of this Court as well as the Act of 2001 by express wording inasmuch the parties adopted Singapore as the exclusive place of arbitration.

- Apart from that, it appears from the correspondence as annexed by the petitioner that the arbitral tribunal also ignored the respondent Nos. 3 and 4 as parties to the arbitration, and admittedly from the plain reading of the agreement, it appears that the respondent Nos. 3 and 4 are not implicated in any manner. On the basis of the record, it is apparent that the interim relief is being sought against such persons who are not at all parties to the proceeding.

- Considering the facts and circumstances and for the above reasons, I find no merit in this application. Accordingly, the application under section 7Ka of the arbitration Act of 2001 is dismissed. Interim order, if any, be vacated.