IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH (HIGH COURT DIVISION)

Admiralty Suit No. 27 of 2005

Decided On: 30.07.2006

Appellants: HRC Shipping Limited

Vs.

Respondent: M.V. X- Press Manaslu and Ors.

**Hon’ble Judges:**Shamim Hasnain, J.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Rafique-ul Huq and S.K. Siddique, Advocates

For Respondents/Defendant: M. Hafizullah, Md. Al-Amin Sarker and Muhammad Ohiullah, Advocates

Subject: arbitration

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

Citing Reference:

Discussed

5

Distinguished

1

Mentioned

10

Case Note:

arbitration - Proceedings - Stay of - Section 10 of arbitration Act, 2001 - Present application filed seeking order of stay of all further proceedings in Admiralty Suit herein and to refer disputes to arbitration under Section 10 of arbitration Act - Whether case made out for grant of relief as prayed - Held, definition of international commercial arbitration makes no distinction between international commercial arbitration which takes place in Bangladesh or outside Bangladesh - Instant Applications do not attempt to oust jurisdiction of Bangladesh courts - Merely keeps Bangladeshi proceedings in abeyance till disposal of arbitration proceedings - Court inclined to stay litigation pending before Court - Application allowed. [46], [47]

Disposition:

Application Allowed

JUDGMENT

Shamim Hasnain, J.

- This application has been filed on behalf of the defendants No. 5 and 6, Sea Consortium Pte. Lid., for an order of stay of all further proceedings in the Admiralty Suit No. 27 of 2005 and to refer the disputes to arbitration under section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001, on the ground, inter alia, that the plaintiff and the defendants No. 5 and 6 had, by an agreement in writing dated 24.2.2004 agreed to refer to arbitration the matters in respect of which the suit is brought.

- The case of the plaintiff in brief is as follows:

The plaintiff carries on business as a carrier of goods in containers and also acts as a feeder operator. During the course of its business, the plaintiff entered into a slot charter agreement dated 24.2.2004 (“the Agreement”) with Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd., Singapore, the defendants No. 5 and 6. Under the Agreement each party was required to make available two vessels which would be able to operate a twice weekly service on a 14 day round voyage between the ports of Colombo and Chittagong. Pursuant to the terms of the Agreement, the plaintiff deployed two vessels, MV Bangla Bijoy and MV Banga Banik and Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd. deployed two vessels, MV Jaami and MV X-Press Resolve.

- Pursuant to the Agreement, the plaintiff received export cargo from certain main line operators, the defendant Nos. 8 to 14 and shipped 53 containers containing the said cargo on the vessel MV Jaami in the slot allotted to the plaintiff. MV Jaami sailed from Chittagong on 21.12.2004; on 27.12.2004 the plaintiff was informed by Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd. that while MV Jaami was taking berth at Colombo, Sri Lanka on 26.12.2004, it was hit by a tsunami, as a result of which the containers laden with cargo dropped into sea and the cargo in the containers washed away. The Master of MV Jaami lodged Marine Note of Protest on 26.12.2004 at Colombo. Sri Lanka.

- The plaintiff subsequently instituted the instant Admiralty Suit wherein it held defendants No. 5 and 6 Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd. responsible for all the consequences flowing from the loss of cargo and claimed payment of compensation for loss of cargo and containers of the different main line operators. Upon a subsequent application of the plaintiff the vessels, M.V. X-Press Manaslu and MV X-Press Resolve, sister vessels of MV Jaami, were arrested by this Court as security for the plaintiffs claim. The vessels were subsequently released by an order of this Court which was upheld by the Appellate Division.

- The present application arises as a result of clause 18 of the Agreement referred to in paragraph 3 of the plaint, which reads as follows:–

“18. The parties shall attempt, among themselves, to settle all controversies or claims arising out of or relating to this Agreement, or any breach thereof. Any claim that the parties are unable to so settle shall be referred to arbitration in London in accordance with the arbitration Act, or any amendment thereto for the time being in force in London. The arbitration decision shall be final and binding upon the parties. The costs of arbitration shall be shared equally by the parties.

The construction, validity and performance of this Agreement shall be covered in all respect by English Law.”

- Clause 2 of Addendum No. 3 of the Agreement provides for issuance of bill of lading as follows:

“Issuance of Bill of Lading (B/L) - Seacon bill of lading will be issued to HRC listing the quantity and type of containers laden on its vessel(s). The B/L shall govern the relations between the parties except for the provisions made in this Agreement and its attachments.”

- The bill of lading under the Agreement was issued to the plaintiff by Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd., Singapore for shipment of cargo on account of different main line operators in the allotted slot. The claim of the plaintiff arises out of the said bill of lading issued under the Agreement and is for breach of contract carnage.

- Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd., Singapore (“Sea Consortium”) commenced arbitration proceedings and gave notice thereof to the plaintiff on 22.12.2006 seeking the plaintiffs consent in respect of appointment of an arbitrator nominated by Sea Consortium as required under the Agreement and the provisions of the English arbitration Act. It appears from the correspondence that the plaintiff also agreed not to pursue any court action against the defendant Nos. 5 and 6 in Bangladesh or elsewhere and to submit the dispute to arbitration in London pursuant to the terms of the Agreement.

- The plaintiff has filed a written objection against Sea Consortium’s application for stay of the instant proceedings. The plaintiffs averments in the written objection are that the loss of the plaintiffs cargo on board MV Jaami is due to the misconduct and negligence of the Master, owner and crew members of MV Jaami. The plaintiff further avers that the cargo was lost due to the failure of the Master, owner and crew members of MV Jaami to exercise due diligence to secure the cargo and their failure to salvage the cargo. The plaintiff further avers that the vessel, MV Jaami was not seaworthy. It appears that the plaintiff has appointed A Hossain & Associates, Law Offices, Bangladesh, on 24.4.2006 to take up the matter with the English lawyers of defendants No. 5 and 6, Messrs Holman Fenwick a Willan, Singapore to proceed with the arbitration as well as to continue with the instant Bangladesh proceedings.

- In a supplementary affidavit filed on behalf of Sea Consortium, it is stated that the plaintiff has agreed to take part in the arbitration proceedings in London and also agreed to take part in the selection and appointment of a sole arbitrator. Separate exchanges between the lawyers of the plaintiff and Sea Consortium have been annexed to the affidavit. These include (a) letter dated 22.12.2005 of Messers Holman Fenwick & Willan requesting consent for appointment of Mr. TR Marshall as sole arbitrator for resolution of the dispute under the slot charter agreement, (b) letter dated 23.4.2006 of A. Hossain & Associates proposing the names of three persons and suggesting that any one of them be appointed as sole arbitrator, and (c) letter dated 3.5.2006 of Mr. Mark Hamsher confirming appointment as arbitrator and enclosing an invoice in respect of 50% of the appointment fee.

- Dr. M. Zahir, the learned Advocate for the defendants No. 5 and 6 in support of his application submits that the proceedings should be stayed pursuant to the provisions of sections 7 and 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 (“2001 Act”). He submits that since the parties have agreed to proceed with arbitration on the basis of the arbitration clause of the Agreement, there should not be parallel proceedings adjudicating the same issue. He refers to Part IV of the Final Report on Lis Pendens and arbitration of the ILA Committee on International Commercial arbitration dated June 2006. He further refers to the provisions of the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards and Article 8(1) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial arbitration. Dr. M. Zahir argues that the text of section 3 of the 2001 Act has caused confusion with regard to interpretation of the law in relation to international commercial arbitration taking place outside Bangladesh. He further submits that although there is a statutory obligation on the courts to stay their proceedings pursuant to section 10 of the 2001 Act, there are a number of situations in which, in addition to the statutory obligation, the courts may assert an inherent jurisdiction to stay their proceedings. In this context he refers to the definitive treatise on arbitration Law by Robert Merkins (AL Service. Issue No. 39, 10 December 2004) and submits that the English courts have recognized four types of situation in which the residual power to stay proceedings may be used:

- There may be arbitration agreements which fall outside the English arbitration Act, 1996, e.g. because they are not in writing.

- There may be arbitration agreements within the English arbitration Act, 1996 but which are not within the mandatory stay provisions in section 9 of the English arbitration Act, 1996.

- The agreement in question may be for some other dispute resolution process rather than arbitration, and

- There may be a dispute between the parties regarding the very existence or scope of the arbitration clause and in which the courts have a parallel jurisdiction with the arbitrators to resolve the jurisdictional issue.

- He further refers to the decisions of the English court in Roussel-Uclaf v. GD Searle & Co. Ltd. and GD Searle & Co. [1978] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 225 and Etri Fans Ltd. v. N.M.B. (U.K.) Ltd. [1987] 1 W.L.R. 1110 where the Court had recognised its inherent jurisdiction to stay the proceedings. Dr. Zahir further submits that section 9 of the English arbitration Act 1996 is in substance similar to that of section 10 of the 2001 Act, particularly section 10(2) thereof which is identical to section 9(4) of the English Act. He argues that the order of stay should not oust the jurisdiction of this Court but will keep the proceedings of the Court in abeyance until resolution of the dispute through arbitration.

- On behalf of the plaintiff, Mr. Rafique-ul Huq refers to section 3 of the arbitration Act, 2001 and argues that it is clear that sections 7 and 10 of the 2001 Act applies only when the arbitration proceedings are taking place in Bangladesh. He submits that this position, notwithstanding the position in England, is required to be addressed on the basis of Bangladeshi provisions. In this context he refers to the decisions of Canada Shipping and Trading SA v. T.T. Katikaayu and another LEX/BDAD/0067/2001 : 54 DLR 93, Unicoi Bangladesh Blocks Thirteen and Fourteen (formerly named Occidental of Bangladesh) and another v. Maxwell Engineering Works Ltd. and another 56 DLR 2004 (AD) 166 and Uzbekistan Airways v. Air Spain Ltd. 10 BLC 615. Mr. Rafique-ul Huq refers to paragraphs 8 and 11 of the Canada Shipping case and submits that the Court being superior Court in jurisdiction can be ousted by an arbitration proceeding if there is a specific reference in the arbitration clause to oust the jurisdiction. This is simply because the parties have agreed to that and made it a part of the contract. But there is no such reference in the arbitration clause to oust the jurisdiction of this Court. He further submits that the Court in the Canada Shipping case exercised its inherent jurisdiction to reject the application for stay. He submits that section 10 of the 2001 Act has no manner of application regarding foreign arbitral proceedings even though the foreign arbitral award can be enforced in this country pursuant to provisions of section 3(2) read with sections 45 to 47 of the 2001 Act. Mr. Huq refers to paragraphs 11 and 15 of the Unicoi case where it is stated that in view of the provisions of section 2(g) and section 3(1) and 3(4) of the Act of 2001 the contention of the learned Counsel as to maintainability of the suit because of the provisions in sections 7, 10 and 20 of the 2001 Act is not legally well founded. It has been further stated that the law as in sections 3(1) and 3(4) of the 2001 Act barring the Court from granting an order of injunction is limited in application as, of arbitration being held outside of Bangladesh.

- Mr. Huq further refers to the decisions in the case of State of Orissa v. S.K. Agarwalla 1999 (3) RAJ 570 (SC), the case of Sukanya Holdings Pvt. Ltd. Vs. Jayesh H. Pandya and another 2003 (2) RAJ-2 (SC) and Investments Pvt. Ltd. Vs. M/S. Aruna Hotels Ltd. and others 2004(3) RAJ 133 (Mad) in respect of bifurcation of cause of action or parties,

- I have perused the application and considered the submissions of the learned advocates for the respective parties. The provisions concerning stay of proceedings in Bangladesh Courts in respect of any matter agreed to be referred to arbitration are contained in section 10 of the Shalish Ain 2001 (the arbitration Act, 2001). The section reads as follows:

“10. Arbitrability of the dispute - (1) Where any party to an arbitration agreement or any person claiming under him commences any legal proceedings against any other party to the agreement or any person claiming under him in respect of any matter agreed to be referred to arbitration, any party to such legal proceedings may, at any time before filing a written statement, apply to the Court before which the proceedings-are pending to refer the matter to arbitration.

(2) Thereupon, the Court shall, if it is satisfied that an arbitration agreement exists, refer the parties to arbitration and stay the proceedings, unless the Court finds that the arbitration agreement is void, inoperative or is incapable of determination by arbitration.

(3) Notwithstanding that an application has been made under sub-section (1) and that the issue is pending before the judicial authority an arbitration may be commenced or continued and award made”

- The above provision requires any court in Bangladesh to stay proceedings and refer the parties to arbitration where the proceedings have been initiated in respect of the subject matter of the proceedings. The application of the section is mandatory as to the grant of a stay if certain conditions are fulfilled. The conditions arc, first, that the person asking for a stay must be a party to the arbitration agreement, or must claim under such a party, and, secondly, that such person must make his application for a stay at any time before filing a written statement. All these conditions appear to have been fulfilled by Sea Consortium Pte. Ltd.

- The corresponding provision of section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 in the old arbitration Act is section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940. Section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940 reads as follows:

“34. Power to stay legal proceedings where there is an arbitration agreement-Where any party to an arbitration agreement or any person claiming under him commences any legal proceedings against any other party to the agreement or any person claiming under him in respect of any matter agreed to be referred, any party to such legal proceedings may, at any time before filing a written statement or taking any other steps in the proceedings, apply to the judicial authority before which the proceedings are pending to stay the proceedings; and if satisfied that there is no sufficient reason why the matter should not be referred in accordance with the arbitration agreement and that the applicant, was, at the time when the proceedings were commenced, and still remains, ready and willing to do all things necessary to the proper conduct of the arbitration, such authority may make an order staying the proceedings.”

- Unlike the provisions of section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 the power of the court to stay a suit under section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940 was within the absolute discretion of the court. However, the discretion vested in the court was required to be properly and judicially exercised keeping in view the interest of justice and the balance of convenience and inconvenience.

- The plaintiff has tried to exclude the grant of such a stay on the basis of section 3(1) of the 2001 Act and the interpretation that has been attributed to that section in a few judgments of the High Court Division and the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, namely Canada Shipping Vs. TT Katikaayu 54 DLR 2002 (HCD) 93, Uzbekistan Airways v. Air Spain Ltd. 10 BLC (2005) (HCD) 615 and Unicoi Bangladesh v. Maxwell 56 DLR 2004 (AD) 166.

- The High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh has held, in Canada Shipping and Trading SA v. TT Katikaayu and another reported in LEX/BDAD/0067/2001 : 54 DLR 93, that, as a result of section 3(1), section 10 of the 2001 Act is not applicable and the application to stay the proceeding before this court should not be entertained considering the facts that it involves arbitration proceeding in a foreign country and not in Bangladesh and the application is not concerning an arbitration award but concerning an arbitration proceeding." That is to say, the High Court Division has held that recourse cannot be made to section 10 to stay proceedings in Bangladesh where the arbitration takes place outside Bangladesh. Canada Shipping is one of the earliest cases on the 2001 Act.

- Following the decision in Canada Shipping, a Division Bench of the High Court Division in Uzbekistan Airways v. Air Spain Ltd. 10 BLC 615 has held that sections 7 and 10 of the 2001 Act has no manner of application to arbitration proceedings taking place outside of Bangladesh.

- The decision dated 8.11.2001 in the Canada Shipping case by Mr. Justice KM Hasan establishes two propositions, i.e.:

i. recourse cannot be made to section 10 of the 2001 Act to stay proceedings in Bangladesh where the arbitration takes place outside Bangladesh.

ii. parties should be restrained from proceeding with foreign arbitration proceedings till disposal of the suit.

- The above decision is in conflict with another order dated 31.10.2001 by the same judge in Company Matter No. 41 of 2000, Integrated Service Limited v. Technology Resources Industries Bangladesh [unreported] in an application for stay of proceedings on the basis of sections 10, 7 and 8 of the 2001 Act.

- The following order was passed:

“During the pendency of the matter the present petitioner, Integrated Services Ltd., has come with this application for staying the proceeding on the ground that it has invoked the arbitration clause of the joint venture agreement and an arbitration Proceeding has already been initiated in Singapore.

… in exercise of the inherent jurisdiction of this court 1 think an order staying the proceeding of the matter will be just and equitable keeping in mind that the stay order does not, however, oust the jurisdiction of this Court but keeps it in abeyance till the arbitration proceeding comes to an end.

In view of the above, the application is allowed. The proceeding or this matter between the petitioner and the respondents is stayed till disposal of the arbitration proceeding.”

- The facts of the instant case and the point of law in issue is clearly distinguishable from that which concerned the parties in Unicoi Bangladesh Vs. Maxwell 56 DLR 2004 (AD) 166 and as such reliance upon the case of Unicoi cannot be made in deciding the instant matter. The Unicoi case concerned an appeal against the grant of a temporary injunction by the Joint District Judge restraining the defendant from proceeding with arbitration. As is evident from paragraph 6 of the judgment, the defendants had a pending application under section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940, for staying the proceeding of the suit. The issue of stay of proceedings had not been resolved, at the time that the Unicoi case was reported. Thus, the decision in Unicoi case related to the application for temporary injunction and not for stay of proceedings under the old section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940. Moreover, as stated above, the old section 34 of the arbitration Act, 1940 is substantially different from its corresponding section in the new arbitration Act, 2001, in that the old section 34 conferred discretionary power on the judicial authority to stay the proceedings while the new section 10 confers a mandatory duty on the courts to refer the parties to arbitration. As such, the Unicoi case which was a case under the old arbitration Act, 1940 is not helpful in deciding the issues involved in the present case which requires interpretation of the stay provisions of the new arbitration Act, 2001.

- The interpretation of the stay provisions as contained in sections 7 and 10 of the Act is discussed in the backdrop of the above facts and the conflicting decisions and the different interpretation that has been given to section 3(a) of the 2001 Act. There appears to be no decisive authority on this point.

- In rendering my judgment it is borne in mind that the avowed object of the 2001 Act is to establish a uniform legal framework for the fair and efficient settlement of disputes arising in international commercial arbitration and to recognize and enforce foreign arbitral award. In pursuance of the above objects our Legislature appears to have prepared the 2001 Act on the basis of the Model Law on International Commercial arbitration adopted by the United Nation Commissions on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) in 1985.

- The General Assembly of the United Nations has recommended that all countries give due consideration to the said Model Law, in view of the desirability of uniformity of the law of arbitral procedures and the specific needs on international commercial arbitration practice. General Assembly Resolution 40/72 adopted in the 12th plenary meeting dated 11.12.1985 reads as follows:-

“…Convinced that the Model Law, together with the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards and the arbitration. Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law recommended by the General Assembly in its resolution 31/98 of 15 December 1976, significantly contributes to the establishment of a unified legal framework for the fair and efficient settlement of dispute arising in international commercial relations,

………………………………..

- Recommends that all States give due consideration to the Model Law on International Commercial arbitration, in view of the desirability of uniformity of the law of arbitral procedures and the specific needs of international commercial arbitration practice.”

[emphasis added]

The Explanatory Note by the UNCITRAL Secretariat on the Model Law on International Commercial arbitration states that the model law was chosen as the vehicle for harmonisation and improvement in view of the flexibility it gives to states in preparing new arbitration laws. It is advisable to follow the model law as closely as possible since that would be the best contribution to the desired harmonisation and in the best interest of the users of international arbitration, who are primarily foreign parties and their lawyers".

- Accordingly, pursuant to the General Assembly Resolution, interpretation of the 2001 Act which is based on the UNCITRAL Model Law requires to “give due consideration to the Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration” so that the aim of “harmonisation” of arbitral proceedings and the “desirability of uniformity of the law of arbitral procedures and specific needs of international commercial arbitration practice” is achieved.

- Mr. Justice ABM Khairul Haque in his judgment in M/s. Strains Construction Company v. Government of Bangladesh represented by Chief Engineer, Roads and Highways Departments 22 BLD (HCD) 236 has observed as follows:-

“11. The United Nations Commission on International Commercial arbitration prepared certain model laws known as UNCITRAL Model Law. The Salish Ain, 2001, repealing the earlier arbitration Act, 1940, is prepared on that model. The whole purpose of the new enactment is that the arbitration proceeding may proceed with minimum interference from Court, unless it is a question of jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal.”

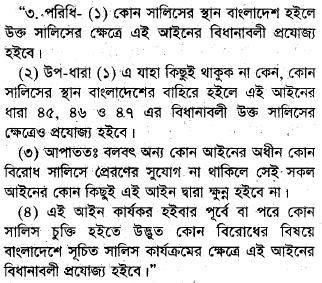

- Turning to the provisions of the 2001 Act, a careful reading of the provisions of the 2001 Act leads to the clear conclusion that sub-section (1) of section 3 is an inclusive definition and it does not exclude the applicability of section 10 to arbitration which is not being held in Bangladesh. The Bengali text which is the official text of the 2001 Act is more accurate as to the intention of the legislature. Section 3(1) of the Act reads as follows:-

- It is evident that section 3(1) provides that 2001 Act would apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. It does not state that it would not apply where the place of arbitration is not in Bangladesh. Neither does it state that the 2001 Act would “only” apply if the place of arbitration is Bangladesh.

- The provision of section 3(1) of the 2001 Act suggests that the intention of the legislature was to make the 2001 Act compulsorily applicable to arbitration, including an international commercial arbitration that takes place in Bangladesh. Parties cannot by agreement override or exclude the non-derogable provisions of the 2001 Act in such arbitrations. However, section 3(1), does not imply that the provisions of the arbitration Act would not be applicable to arbitration proceedings taking place outside Bangladesh.

- The above interpretation is consistent with the provisions of the UNCITRAL Model law. Article 1(2) (scope of application) of the UNCTRAL model law reads as follows:

“Article 1. Scope of application. (1)…

(2) The provisions of this Law, except articles 8, 9, 35 and 36,' apply only if the place of arbitration is in the territory of this State.”

- Article 8 relates to the stay of proceedings and reads as follows:

“Article 8. arbitration agreement and substantive claim before court (1) court before which an action is brought in a matter which is the subject of an arbitration agreement shall, if a party so requests not later than when submitting his first statement on the substance of the dispute, refer the parties to arbitration unless it finds that the agreement is null and void, inoperative or incapable of being performed.”

- Thus, the UNCITRAL Model law, firstly excludes the application of Article 8 from the application of Article 1(2) and, secondly, specifically states that Model law only applies if the place of arbitration is in the territory of the State.

- The Explanatory Note by the UNCITRAL Secretariat on the model law on international commercial arbitration states as follows:

“12. …According to article 1(2), the model law as enacted in a given State would apply only if the place of arbitration is in the territory of that State. However, there is an important and reasonable exception. Article 8(1) and 9 which deals with recognition of arbitration agreements, including their compatibility with interim measures of protection, and articles 35 and 36 on recognition of arbitral awards are given a global scope, i.e. they apply irrespective of whether the place of arbitration is in Unit State or in another State and, as regards articles 8 and 9, even if the place of arbitration is not yet determined.”

[emphasis added]

- Two points may be made from the above- (i) the Model law specifically excludes application of Article 8 from the application of Article 1(2) for the reasons quoted above; and (ii) Article 1(2) specifically includes “only” to restrict the application of the Model Law unlike section 3 of the 2001 Act which would indicate the intention of the Bangladeshi Legislature not to restrict the application of the 2001 Act only to arbitrations taking place in Bangladesh.

- If the interpretation of sections 3(1) and 10 as given in the Canada Shipping case and Uzbekistan Airways case is accepted, it would derive a party of lawful and agreed remedy inasmuch as in international commercial arbitrations taking place out of Bangladesh the party would also be unable to apply for interim relief in Bangladesh even though properties and assets are in Bangladesh. Thus a party may not be able to get any interim relief at all.

- This is reflected in the Indian decision of Olex Focas Pte. Ltd. Vs. Skodaexport Co. Ltd. 2000 AIR (Del) 171 where the issue was mainly whether interim injunction can be granted by a Court when the arbitration was taking place outside of India, the Court was of the following view:

“60. I have considered the rival contentions, advanced by the learned counsel for the parties. I have also considered the cases which have been cited at the bar. A careful reading and scrutiny of the provisions of 1996 Act leads to the clear conclusion that sub-section (2) of Section 2 is an inclusive definition and it does not exclude the applicability of Part I to this arbitration which is not being held in India. The other clauses of Section 2 clarify the position beyond any doubt that this Court in an appropriate case can grant interim relief interim injunction. A close reading of relevant provisions of the Act of 1996 leads to the conclusion that the Courts have been vested with the jurisdiction and powers to grant interim relief. The powers of the Court are also essential in order to strengthen and establish the efficacy and effectiveness of the arbitration proceedings.

- [sic] The arbitrators perhaps cannot pass orders regarding the properties which are not within the domain of their jurisdiction and if the Courts are also divested of those powers, then in some cases it can lead to grave injustice. arbitration proceedings take some time and even after an award is given, some time is required for enforcing the award. There is always a time-lag between pronouncement of the award and its enforcement. If during that interregnum period, the property/funds in question are not saved, preserved or protected, then in some cases the award itself may become only paper award or decree. This can of course never be the intention of the legislature. While interpreting the provisions of the Act the intention of the framer of the legislation has to be carefully gathered.”

- Moreover, our Legislature has also catered for the parties to choose the place of arbitration in the 2001 Act. Section 26 of the 2001 Act allows parties to agree to a place of arbitration. If the interpretation of the lawyers of the plaintiff is accepted in respect of the application of the provisions of the 2001 Act, such a provision as section 26 would have been unnecessary. Section 26 of the 2001 Act reads as follows:

“26. Place of arbitration- (1) The parties shall be free to agree on the place of arbitration.

(2) Failing such an agreement referred to in sub-section (1), the place of arbitration shall be determined by the arbitral tribunal having regard to the circumstances of the case, including the convenience of the parties.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), or sub-section (2), the arbitral tribunal may, unless otherwise agreed by the parties, meet at any place it consider appropriate for consultation among its members, for hearing witness, experts or the parties, or for inspection for documents, goods and other property.”

- The above views are reflected in the decision of the Indian Supreme Court in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA 2002 AIR (SC) 1432 as well as several decisions of the High Court of India which includes the above case of OIex Focas Ptv. Ltd. Vs. Skodaexport Co. Ltd. 2000 AIR (Del) 171.

- The Supreme Court of India in Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA 2002 AIR (SC) 1432, addressed the same point with which the instant application is, concerned, i.e. whether stay of court proceedings can be made when an arbitration proceeding takes place abroad. The Supreme Court of India categorically concluded that the applicability of the provisions of the arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 was not restricted by section 2(2) [similar provision as section 3 of the 2001 Act] to arbitration/international commercial arbitration taking place in India.

- The case of Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA 2002 AIR (SC) 1432 extensively discusses the matter and states as follows:

“15. It is thus necessary to see whether the language of the said Act is so plain and unambiguous as to admit of only the interpretation suggested by Mr. Sen. It must be borne in mind that the very object of the arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996, was to establish a uniform legal framework for the fair and efficient settlement of disputes arising in international commercial arbitration…..

- A reading of the provisions shows that the said Act applies to arbitrations which are held in India between Indian nationals and to international commercial arbitrations whether held in India or out of India. Section 2(f) defines an international commercial arbitration, The definition makes no distinction between international commercial arbitrations held in India or outside India………..

- Section 2(a) defines “arbitration” as meaning any arbitration whether or not administered by a permanent arbitral institution. Thus, this definition recognises that the arbitration could be under a body like the Indian Chamber of Commerce or the International Chamber of Commerce. Arbitrations would be held, in most cases, out of India. Section 2(c) provides that the term “arbitral award” would include an interim award.

- Now let us look at sub-section (2), (3), (4) and (5) of Section 2. Sub-section (2) of Section 2 provides that Part I would apply where the place of arbitration is in India. To be immediately noted that it is not providing that Part I shall not apply where the place of arbitration is not in India. It is also not providing that Part I will “only” apply where the place of arbitration is in India (emphasis supplied). Thus the Legislature has not provided that Part I is not to apply to arbitrations which take place outside India. The use of the language is significant and important. The Legislature is emphasizing that the provisions of Part I would apply to arbitrations which take place in India, but not providing that the provisions of Part 1 will not apply to arbitrations which take place out of India, The wording of sub-section (2) of Section 2 suggests that the intention of Legislature was to make provisions of Part I compulsorily applicable to an arbitration, including an international commercial arbitration, which takes place in India. Parties cannot, by agreement, override or exclude non-derogable provisions of Part I in such arbitrations by omitting to provide that Part I will not apply to international commercial arbitrations which take place outside India the effect would be that Part I would also apply to international commercial arbitrations held out of India. But by not specifically providing that the provisions of Part 1 apply to international commercial arbitrations held out of India, the intention of the Legislature appears to be to allow parties to provide by agreement that Part 1 or any provision therein will not apply. Thus in respect of arbitrations which take place outside of India even the non-derogable provisions of Part I can be excluded: Such an agreement may be express or implied.”

- The definition of “International Commercial Arbitration” contained in section 2(c) of the 2001 Act reflects the definition provided in the Indian Act. “international Commercial Arbitration” means “an arbitration relating to disputes arising out of legal relationship, whether contractual or not, considered as commercial under the law in force in Bangladesh and where at least one of the parties is-

(i) an individual who is a national of, or habitually resident in any country other than Bangladesh; or

(ii) a body corporate which is incorporated in any country other than Bangladesh; or

(iii) a company or an association or a body of individuals whose central management and control is exercised in any country other than Bangladesh; or

(iv) the government of a foreign country.”

- It is to be noted that the definition of international commercial arbitration makes no distinction between international commercial arbitration which takes place in Bangladesh or international commercial arbitration which takes place outside Bangladesh. If the proposition of the plaintiff is correct then the provision for enforcement of foreign arbitral award will become redundant as prior to completion of the foreign proceedings, one of the party is free to obtain an order injuncting the foreign arbitration proceedings and as such there would not be any foreign arbitral award to enforce. Moreover, unless one of the proceedings is stayed, the dispute is open to resolution in multiple forums resulting in multiplicity of proceedings.

- Any submission on ouster of jurisdiction is not relevant for disposal of the instant application as sections 7 and 10 of the 2001 Act do not attempt to oust the jurisdiction of the Bangladesh courts but, merely keeps the Bangladeshi proceedings in abeyance till disposal of the arbitration proceedings as has been observed by Mr. Justice K.M. Hasan in Company Matter No. 41 of 2000, Integrated Service Limited v. Technology Resources Industries Bangladesh [unreported], in this context the observations made by the Appellate Division in Bangladesh Air Service (Pvt.) Limited v. British Airways PLC 49 DLR (AD) 187 in respect of submissions on arbitration agreement impinging on the sovereignty of the country becomes relevant:

“26…The plea of sovereignty and interest of the country and its citizen, if accepted, will render foreign arbitral jurisdiction absolutely nugatory. We venture to say that such a consequence will itself be opposed to public policy, for no country lives in an island these days. Foreign arbitration clause is an integral part of the international trade and commerce today.”

- As stated earlier, Dr. M. Zahir has relied upon the inherent power of the Court to stay proceedings and referred to the cases of Roussel-Uclaf Vs. GD Searle & Co. Ltd. and GD Searle & Co. [1978] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 225 and Etri Fans Ltd., NMB. (U.K.) Ltd. [1987] 1-W.L.S.R. 1110 where the Courts had recognized its inherent jurisdiction to stay the proceedings. I refer to another English case, viz., Channel Tunnel Group Ltd. and others v. Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd. and others [1993] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 301 wherein Lord Browne-Wilkinson sitting in the House of Lords stayed proceedings exercising its inherent jurisdiction. The decision was based on the principle that a court will enforce a dispute resolution contract between parties in the same way that any other contract between parties are enforced. The relevant paragraphs of the Channel Tunnel Group Ltd. and others v. Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd. and others [1993] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 301 are quoted below:

“…It is true that no reported case to this effect was cited in argument, and is the only one which has subsequently come to light, namely Etri Fans Ltd. v. N.M.B. 9 U.K.) Ltd.; [1987] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 565; [1987] 1 W.L.R. 1110, the Court while assuming the existence of the power did not in fact make an order. I am satisfied however that the undoubted power of the Court to stay proceedings under the general jurisdiction, where an action is brought in breach of an agreement to submit disputes to the adjudication of a foreign Court, provides a decisive analogy. Indeed until 1944 it was believed that the power to stay in such a case derived from the arbitration statutes. This notion was repudiated in Racecourse Betting Control Board v. Secretary for Air, [1944] Ch. 114, but the analogy was nevertheless maintained. Thus, per Lord Justice MacKinnon at p. 126:

- It is, I think, rather unfortunate that the power and duty of the court to stay the action [on the grounds of a foreign jurisdiction clause] was said to be under section 4 of the arbitration Act 1889. In truth, that power and duty arose under a wider general principle, namely, that the court makes people abide by their contracts, and, therefore, will restrain a plaintiff from bringing an action which he is doing in breach of his agreement with the defendant that any dispute between them shall be otherwise determined.

- So also, in cases before and after 1944, per Lord Justice Atkin in The Athenee, (1922) 11 LI. L. Rep. 6, and Mr. Justice Willmer in The Fehrmarn, [1957] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 511 at p. 513; [1957] 1 W.L.R. 815 at p. 819, approved on appeal [1957] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 551 at p. 556; [1958] 1 WLR 159 at p. 163. I see no reason why the analogy should not be reversed. If it is appropriate to enforce a foreign jurisdiction clause under the general powers of the Court by analogy with the discretionary power under what is now s. 4(1) of the 1940 Act to enforce an arbitration clause by means of a stay, it must surely be legitimate to use the same powers to enforce a dispute-resolution agreement which is nearly an immediately effective agreement to arbitrate, albeit not quite. I would therefore hold that irrespective of whether cl. 67 falls within s. 1 of the 1975 Act, the Court has jurisdiction to stay the present action.

My Lords, I also have no doubt that this power should be exercised here. This is not the case of a jurisdiction clause, purporting to exclude an ordinary citizen from his access to a Court and featuring inconspicuously in a standard printed form of contract. The parties here were large commercial enterprises, negotiating at arms length in the light of a long experience of construction contracts, of the types of disputes which typically arise tinder them, and of the various means which can be adopted to resolve such disputes, It is plain that cl. 67 was carefully drafted, and equally plain that all concerned must have recognized the potential weaknesses of the two-stage procedure and concluded that despite them there was a balance of practical advantage over the alternative of proceedings before the national Courts of England and France. Having made this choice I believe that it is in accordance, not only with the presumption exemplified in the English cases cited above that those who make agreements for the resolution of disputes must show good reasons for departing from them, but also with the interests of the orderly regulation of international commerce, that having promised to take their complaints to the experts and if necessary to the arbitrators, that is where the appellants should go. The fact that the appellants now find their chosen method too slow to suit their purposes, is to my thinking quite beside the point.”

- An additional submission of Mr. Rafique-ul Huq in light of few Indian cases cited above is that it is not possible to bifurcate cause of action or parties. Here, in holding a different view, I reproduce a relevant paragraph from Russell on arbitration (21st Edition) page 327:

“Where there are several defendants any one of them who is a party to an arbitration agreement with the Plaintiff can make the application to have the action stayed; it is not necessary that all the defendants should join in the application. The action will only be stayed as against those defendants who are a party to the arbitration agreement.

A bill was filed to restrain the lessees of a mine from doing certain acts. The lease contained in an arbitration clause. Of three defendants only two were willing to concur in an application to have the proceedings stayed, but a stay was granted and the Court of Appeal in Chancery upheld the decision. (Willesford v. Watson (1873) L.R. 8 Ch. 473…)”

- Having regard to the facts and circumstances of the case and the foregoing discussion, J am inclined to stay the litigation pending before this Court. However, since the defendants other than defendants No. 5 and 6 are not parties to the arbitration agreement this suit is stayed only in respect of the defendants No. 5 and 6.