IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH (HIGH COURT DIVISION)

First Appeal No. 209 of 2016

Decided On: 12.12.2021

Appellants: Accom Travels and Tours Limited

Vs.

Respondent: Oman Air S.A.O.C. and Ors.

Hon’ble Judges:Sheikh Hassan Arif, Md. Ashraful Kamal and Ahmed Sohel, JJ.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Hassan M.S. Azim, Advocate

For Respondents/Defendant: Md. Asaduzzaman, Advocate and Probir Neogi, Senior Counsel as Amicus Curiae

Subject: Civil Procedure

**Acts/Rules/Orders:**Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 10; Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 151; Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 89B; Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 9; Companies Act, 1994 - Section 95; Constitution Of The People’s Republic Of Bangladesh - Article 103, Constitution Of The People’s Republic Of Bangladesh - Article 111; Contract Act, 1872 - Section 28

Disposition:

Disposed of

Industry: Aviation

JUDGMENT

Sheikh Hassan Arif, J.

1. Upon a reference by a Division Bench of the High Court Division, the Hon’ble Chief Justice of Bangladesh has sent this matter before this larger bench (full bench).

- Background Facts:

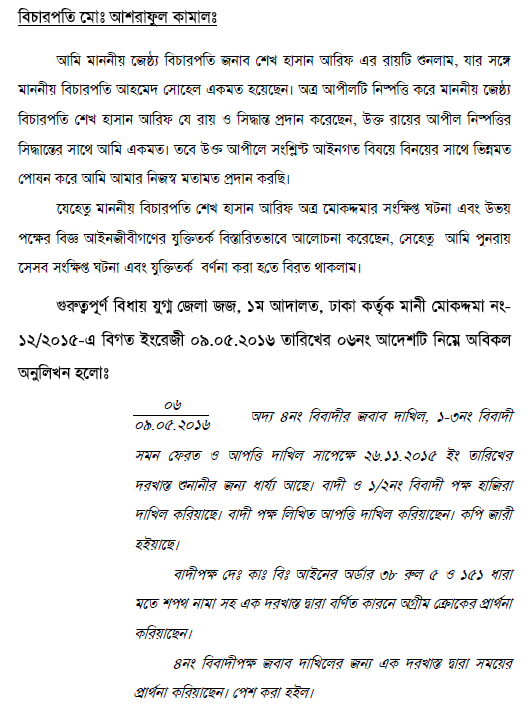

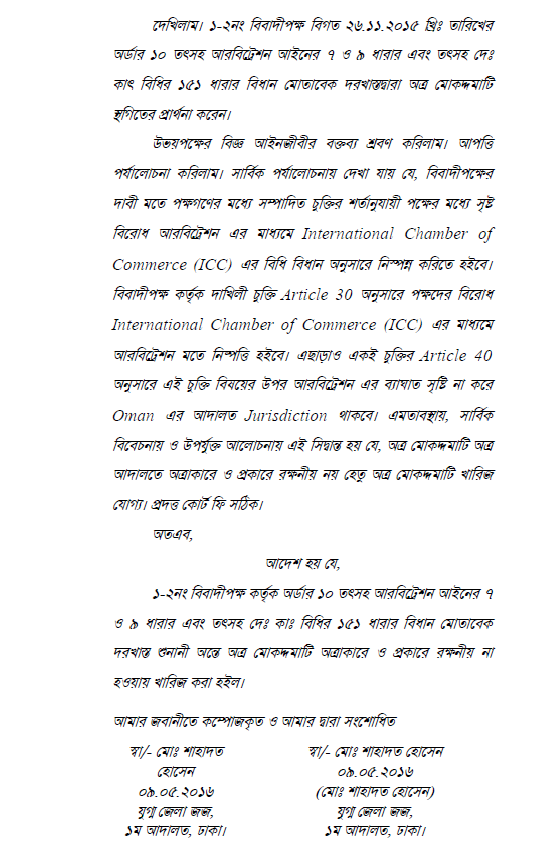

2.1 At the instance of the plaintiff in Money Suit No. 12 of 2015, this appeal was directed against judgment and decree dated 09.05.2016 (decree signed on 12.05.2016) passed by the First Court of Joint District Judge, Dhaka in the said suit allowing an application under Section 10 read with Sections 7 and 9 of the arbitration Act, 2001 and Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 in a modified way and, thereby, dismissing the suit as being not maintainable.

2.2 The appellant, as plaintiff, filed the said Title Suit No. 12 of 2015 before the First Court of Joint District Judge, Dhaka seeking a money decree against the defendant Nos. 1, 2 and 3 jointly and severally on account of damages etc. for an amount of Tk. 78,00,00,000/- and interests. The case of the plaintiff, in short, is that, being a private limited company, it is one of the leading companies in the aviation, travel agency and air freight cargo handling business in Bangladesh. That in the course of its such business, the plaintiff and defendant No. 1 (Oman Air) entered into a G.S.A. agreement on 01.09.2008 followed by a GSSA agreement which were renewed subsequently on 31.08.2013 and 31.04.2013 respectively. That the plaintiff contributed a lot in developing the business of defendant No. 1 in Bangladesh as its G.S.A. and G.S.S.A. given that the defendant No. 1 was comparatively new in Bangladesh market. However, a dispute arose between the parties. Thus, defendant No. 1 (Oman Air) terminated both the agreements vide termination notices dated 18.09.2014 and 29.09.2014 respectively. That the said termination was against the law and terms of the said agreements, and because of such termination, the plaintiff suffered huge loss, as narrated at paragraph-22 of the plaint. That the plaintiff issued legal notice claiming certain amount as against such loss of business and profit, but got no positive response. Accordingly, it filed the said suit against Oman Air (the defendant Nos. 1, 2 and 3) for realization of damages for an amount of Tk. 78,00,00,000/- and interests thereon.

2.3 Upon registration of the said suit and issuance of summons, Oman Air (defendant Nos. 1, 2) and defendant No. 4 entered appearance. Before filing of the written statement, Oman Air (defendant Nos. 1 and 2), on 26.11.2015, filed an application under Section 10 read with Sections 7 and 9 of the arbitration Act, 2001 read with Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure seeking stay of the proceedings of the said suit on the ground that the agreements mentioned in the plaint had arbitration clause for resolving disputes between the parties. Thereupon, the Court below, after hearing the parties, allowed the said application in a modified form in that it dismissed the entire suit on the ground that the suit was not maintainable. Being aggrieved by such dismissal of the suit followed by a decree, the plaintiff preferred this appeal.

2.4 The appeal was fixed for hearing before a division bench of the High Court Division comprising Mr. Justice Sheikh Hassan Arif and Mr. Justice Ahmed Sohel. The only law point for determination in the appeal was whether in view of the provisions under Sections 3(1) and (2) of the arbitration Act 2001, the provisions under Sections 10 and 7 of the said Act would be applicable in respect of an arbitration where the seat of such arbitration was in a foreign country. In the course of hearing, the said division bench found two sets of contrary decisions given by different benches of this Court on the said point of law. Accordingly, the said division bench, without expressing any view of its own, referred the matter to the Hon’ble Chief Justice of Bangladesh for constitution of a larger bench. Thereupon, the Hon’ble Chief Justice of Bangladesh has sent this matter to this bench of the High Court Division.

- Submissions:

3.1 Mr. Hassan M.S. Azim, learned advocate appearing for the plaintiff-appellant, has made the following submissions:

(a) That in view of the provisions under Section 3(1) and (2) of the arbitration Act 2001, the provisions of the said Act, except the provisions for recognition and implementation of the awards as provided by Sections 45, 46 and 47 of the said Act, are not applicable in a proceeding initiated in any Court in respect of the subject matter of an arbitration agreement where the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country. Accordingly, the provisions under Section 10 (seeking stay of the proceedings) and Section 7 (questioning jurisdiction of the Court) cannot be invoked. Thus, the Court below has committed gross illegality in rejecting the plaint entirely holding that the same was not maintainable. In support of his such submissions, he has referred to different decisions of this Court in Canda Shipping vs. TT Katikaayu, 54 DLR (2002)-93, Unicol Bangladesh vs. Maxwell, 56 DLR (AD)-166, Uzbekistan Airways vs. Air Spain Ltd., 10 BLC (2005)-614 as affirmed by the Appellate Division in Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal No. 1112 of 2005 and STX Corporation Ltd. vs. Meghna Group, 64 DLR (2012)-550.

(b) By referring to the decision of a Division bench in the above referred Uzbekistan Airways case, he submits that a division bench of the High Court Division has categorically held therein that the provisions under Section 10 of the said Act are not applicable in view of the provisions under Section 3(2) of the said Act, and that the said decision of the said division bench has been approved by the Appellate Division in Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal No. 112 of 2005. Therefore, he submits that the issue has already been settled by this Court up to the Appellate Division and as such the Court below has committed gross illegality in entertaining the said application filed by the defendant-respondent and thereby rejecting the entire plaint on the ground of maintainability.

(c) Further referring to the decision of a single bench of the High Court Division in STX Corporation case referred to above, he submits that a single bench of the High Court Division, in the said case, elaborately discussed all the above referred decisions on the said point and finally held that the Legislature specifically excluded the application of the provisions of arbitration Act, 2001, apart from the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47, in respect of an arbitration the place of which was outside Bangladesh. Therefore, according to him, in spite of such settled principle of law, it is unfortunate that two single benches of the High Court Division have expressed different views in two cases, which, according to him, should not be regarded as precedents as the same have been expressed against the view taken by the Appellate Division in the above referred Uzbekistan Airways case.

(d) As regards staying of proceedings initiated in a civil Court in respect of the subject matter of arbitration agreement in exercise of inherent power of the Civil Court under Section 151 of the Code, he submits that when there is specific provision under Section 10 of the said Act for staying such proceedings and the application of such provisions has been excluded by Section 3, inherent power of the Court under Section 151 should not be exercised as because such exercise will render the provision under Section 3 of the said Act redundant. In support of his such submissions on this point, he has referred to two decisions of our Appellate Division, namely the decisions in Md. Hazrat Ali vs. Joynal Abedin, 1986 BLD (AD)-45 and Abdul Mohit vs. Social Investment Bank, 61 DLR (AD)-82.

(e) By referring to the decision of a single bench in HRC Shipping case 12 MLR-265, Mr. Azim submits that this decision has been delivered by the said single bench mainly relying on the decision of the Indian Supreme Court in Bhatia International Case (2002) 4 SCC-105 on the ground that our Legislature has omitted the word “only” from Section 3(1) of arbitration Act, 2001, particularly when the corresponding provision in the UNCITRAL Model Law has the said word ‘only’. He submits that the decision in Bhatia Case has already been overruled by the Indian Supreme Court in Bharat Aluminium Co. vs. Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services Inc. (2012) 9 SCC-552 (in short, ‘BHALCO Case’) holding in particular that such omission of the said word “only” by the Legislature does not make any material difference.

3.2 As against above submissions, Mr. Md. Asaduzzaman, learned advocate appearing for the defendant No. 1-respondent, has made the following submissions:-

(i) Although the suit was not liable to be dismissed, yet the proceedings thereof were liable to be stayed on the ground that the parties had agreed by the said two agreements to settle their disputes through arbitration. In this regard, he has referred to the arbitration clauses in the said two agreements.

(ii) That since Section 3 of the arbitration Act has not specifically excluded the application of the provisions under Section 10 of the said Act, the Civil Court in Bangladesh can invoke the said provisions in order to stay the proceedings pending before it and send the matter to resolve the same through arbitration. Therefore, according to him, in the instant case, the Court below should have stayed the proceedings instead of dismissing the entire suit and should have sent the matter to arbitration. In support of his such submissions, he has referred to two decisions of this Court in HRC Shipping Ltd. vs. M.V. X-Press Manaslu and others, 12 MLR(HC) 2007-265 and Southern Solar Power Ltd. vs. BPDB, 25 BLC(2020)-501.

(iii) By specifically referring to Clauses 30 and 40 of both the G.S.A. and G.S.S.A. agreements, he submits that the parties agreed to resolve their disputes through arbitration under the Rules of conciliation and arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce and that they also agreed that the said agreements would be governed and construed in accordance with the laws of Oman with exclusive jurisdiction of the Courts of Oman in respect of the same. This being so, since the parties agreed to settle their disputes through arbitration thereby conferring jurisdiction to the Court of another country, such agreements of the parties should be allowed to be implemented and as such none of the parties should be given any opportunity to frustrate such agreements by taking recourse to civil proceedings.

(iv) By referring to Exception-1 to Section 28 of the Contract Act, 1872 read with Section 36 of the arbitration Act, 2001, he submits that since the parties agreed to resolve their disputes through arbitration thereby agreeing to apply the law of a certain country with exclusive jurisdiction of the Court of that country over the subject matter, the Courts in Bangladesh should stay the proceedings pending before it in respect of the said subject matters of the said agreements by exercising its inherent power under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure, even if it is found that Section 10 of the arbitration Act is not applicable. According to him, such agreements for resolving disputes through arbitration in accordance with the law of a different country thereby giving jurisdiction to the Court of that country in respect of the subject matter is allowed under the law of our country in view of the provisions under Exception-1 to Section 28 of the Contract Act read with Section 36 of the arbitration Act, 2001. In support of his such submissions, he has referred to two decisions of our Appellate Division in M.A. Chowdhury vs. M/s. Mitsui, 22 DLR (SC) (1970)-334 and Bangladesh Air Service (Pvt.) Ltd. vs. British Airways PLC, 17 BLD (AD)(1997)-249. He has also referred to the decisions in A.B.C. Laminart Pvt. Ltd. vs. A.P. Agencies, AIR 1989 (SC)-1239 and M/s. L.T. Societa vs. M/s. Lakshminarayan, AIR 1959 Calcutta-669, as decided by the Superior Courts in India.

3.3 On the point of exercise of inherent power of the Court in a case where there is specific provision of law, we have requested Mr. Probir Neogi, learned senior counsel, to assist this Court as Amicus Curiae. Accordingly, Mr. Neogi has submitted that such power may be exercised for ends of justice and to avoid abuse of the process of Court even where there is specific provisions of law. By referring to a decision of a division bench of our High Court Division in M/s. Ayat Ali & Co. vs. Janata Bank, 40 DLR (1988)-56, Mr. Neogi submits that in the said case although there was specific provision for staying the proceedings of subsequent suit under Section 10, the Court allowed simultaneous hearing of both the suits in order to secure ends of justice. Mr. Neogi has also cited a decision of Privy Council in Annamalay vs. Thornhill, AIR 1931, Privy Council-263 in this regard.

- Deliberations and Findings:

4.1 Admittedly, the parties agreed to settle their disputes through arbitration and the case of the respondent being that the seat of arbitration in both the agreements is Oman, the specific point of law in this appeal is whether the provisions of the arbitration Act, except the provisions under Sections 45-47, are applicable in respect of an arbitration when the seat of such arbitration is in a foreign country. In particular, whether an application under Section 10 read with Sections 7 and 9 of the arbitration Act could be filed by the defendant in the suit concerned. Without resolving this point of law, this Court will not be in a position to resolve the disputes between the parties in the instant appeal. However, as stated above, two sets of contrary decisions given by different benches of this Court are already there on the said point. Accordingly, let us give a short description of the said contrary views expressed by different benches of this Court in the said two sets of cases.

4.2 First Set: Provisions of the arbitration Act, except Sections 45, 46 and 47, will not apply:

(a) Canda Shipping Case, 54 DLR (2002)-93:

In this case, a single bench of the High Court Division (exercising Admiralty Jurisdiction), presided over by his Lordship Mr. Justice K.M. Hasan (as his lordship then was), held as follows (see para-7 of the reported case):

“I have considered the submissions of the learned Advocates of both sides. From a reading of section 3(1) and (2) it appears to me that the Act applies to arbitration where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh and not in a foreign country. Sections 45, 46 and 47 are made exceptions to section 3. So, in my view, section 10 of this Act is not applicable and the application to stay the proceeding before this court should not be entertained considering the facts that it involves arbitration proceeding in a foreign country and not in Bangladesh and the application is not concerning an arbitration award but concerning an arbitration proceeding”.

(Underlines supplied)

(b) Unicol Bangladesh Case, 56 DLR (AD) (2004)-166:

This case went to the Appellate Division against a judgment of a division bench of the High Court Division (exercising civil miscellaneous appellate jurisdiction) in F.M.A. No. 259 of 2001 [Occidental vs. Maxwell, 9 BLC (2004)-96]. Although, the case itself was originated from the provisions of the previous law, namely arbitration Act, 1940 (now repealed), the Appellate Division, while discussing various submissions of the learned advocates of the parties, made the following observation (see para-15 of the reported case):

“…………………………. since we have already mentioned that the law as in sections 3(1) and 3(4) of the Act barring the Court from granting an order of injunction is limited in application as to the arbitration being held in Bangladesh, but not as to matter restraining a particular party from proceeding with arbitration in foreign country in respect of a contract signed in Bangladesh”.

(Underlines supplied)

(c) Uzbekistan Airways case, 10 BLC (2005)- 614 and C.P.L.A. No. 1112 of 2005:

(i) In this case, a division bench of the High Court Division, presided over by his Lordship Mr. Justice Syed Amirul Islam (exercising civil appellate jurisdiction), held as follows (see para-5 of the reported case):

“Here it may further be mentioned that the question mooted by Mr. Nabi had already been considered by both the Divisions of this Court on more than one occasion and both the Divisions consistently held that section 10 of the Act is not applicable to arbitral proceeding in a foreign country and section 3(2) simply lays down the provision that a foreign arbitration award is enforceable within Bangladesh. The courts below also reflected the principles laid down by both the Divisions of this Court in the impugned order. In the course of hearing we had drawn attention of Mr. Nabi to the decision reported in 56 DLR (AD) 166 and the unreported decision of Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal Nos. 73-75/1982 and the case reported in LEX/BDHC/0082/2001 : 54 DLR 93 and 9 BLC 96. In these decisions both the Divisions of this Court had the opportunity to examine the scope of section 10 of the Act and on a careful scrutiny of the scheme and the relevant provisions of the Act both the Divisions have taken the view that section 10 of the Act has no manner of application with regard to foreign arbitral proceeding though the foreign arbitral award can be enforced in this country pursuant to the provisions of section 3(2) read with sections 45-47 of the Act. In that view of the matter, it appears that the scope of section 10 of the Act is well settled and it has been decided more than once by the Appellate Division in the aforesaid two cases that section 10 of the Act does not apply to foreign arbitral proceedings. Therefore, it appears to us that the courts below did not commit any error of law in rejecting the application filed by the appellant as petitioner before the trial Court”.

(Underlines supplied)

(ii) This decision of the said division bench of the High Court Division was, subsequently, affirmed by the Appellate Division in Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal No. 1112 of 2005 wherein the Appellate Division, after reproducing the aforesaid observation of the High Court Division, held that “we do not find any reason to interfere with the judgment and order of the High Court Division”

(d) STX Corporation Ltd. vs. Meghna Group, 64 DLR (2012)-550:

(i) In this case, a single bench of the High Court Division, presided over by his Lordship Mr. Justice Mamnoon Rahman (exercising Special Original Jurisdiction), took up the painstaking job to examine each and every decision so far decided by this Court and the Courts in our neighboring countries. The said case was in respect of an application seeking injunction filed under Section 7Ka the arbitration Act, 2001 and the seat of arbitration therein was in a foreign country. However, elaborately taking into consideration all the decisions on the point, the said Single Bench held as follows:

“18. Section 3 consists of 4 (four) sub-sections. In sub-section (1), it has been categorically stipulated that the provision of the Act of 2001 shall apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. Sub-section (2) deals with the enforcement of foreign arbitration awards in the manner that notwithstanding anything contain in sub-section (1), in case of enforcement of award passed in a foreign arbitration, section 45, 46 and 47 of the Act of 2001 can be invoked. Sub-section (4) stipulates that the provisions of the Act shall apply to the arbitration proceeding in Bangladesh arising out of arbitration agreement concluded prior or subsequent to the coming into force of the Act of 2001. So, on a plain reading of section 3 of the Act, it is very much apparent that the Act of 2001 shall only apply when the place of arbitration or the arbitration proceeding is in Bangladesh.

- The provision as laid down under section 3(2) of the Act affirmed such exclusion by specific manner wherein the legislature categorically stated where and under what circumstances the Act shall apply when the place/proceeding is not in Bangladesh. The intention of the legislature is that the award in the foreign arbitration can be enforced in Bangladesh, as provided in section 45, 46 and 47 of the Act. It means that by section 3(2) of the Act the legislature specifically excluded the application of this law, apart from section 45, 46 and 47, to an arbitration proceeding, the place of which is outside Bangladesh, or in other words a foreign arbitration”.

(Underlines supplied)

(ii) At the time of hearing of this case, a contrary decision of another single bench of this Court was referred to the said bench, namely the case in HRC Shipping Limited vs. MV. Express, 12 MLR (HC) (2007)-265. In respect of the said decision, the said single bench observed as follows (see paragraph-41 of the reported case):

“41. I have full respect to his Lordship for the decision as reported in 12 BLD (AD) 72=44 DLR (AD) 40. But at the same time, when it is clearly found that the judgment passed by the single judge is not based upon the decisions of our Apex Court on the particular point, it cannot be said the same issue is being addressed in a proper manner and any decision in violation of the judgment passed by the Appellate Division cannot be a basis of anything, even cannot be basis to refer the matter for a larger bench. Admittedly, in the HRC case, the High Court Division considered all the international conventions and Indian cases, but it appears from the said Judgment that the decisions of our Appellate Division have not been considered or reflected in a proper manner. As per Article 111 of the Constitution, there is no scope for this Division to go beyond the dictum as laid down by their Lordships in the Appellate Division unless and otherwise their Lordships reviewed their own decision”.

4.3 Second Set: Provisions of the arbitration Act will Apply:

As stated above, two cases by two single benches of this Court in HRC Shipping case, 12 MLR-265 and Southern Solar Case, 25 BLC-501 took a different path and held that the provisions of the arbitration Act 2001, in particular Sections 10 and 7Ka of the arbitration Act, would apply even if the seat of arbitration was agreed to be in a foreign country. Following are the short descriptions of those cases:

(a) HRC Shipping Limited Vs. M.V. X-press Manaslu and others, 12 MLR (HC) 2007, P-265:

(i) A single bench of the High Court Division, presided over by his Lordship Mr. Justice Shamim Hasnain (exercising admiralty jurisdiction), while disposing of an application filed by the defendants under Section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 seeking stay of the proceedings, had the occasion to deal with the same issue. The said single bench therein examined the UNCITRAL Model Law on arbitration and also considered the decisions in Canda Shipping case, Uzbekistan Airways case and Unicol Bangladesh Case, as referred to above. Thereupon, the said single bench concluded as follows:

“32. It is evident that section 3(1) provides that 2001 Act would apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. It does not state that it would not apply where the place of arbitration is not in Bangladesh. Neither does it state that the 2001 Act would “only” apply if the place of arbitration is Bangladesh.

- The provision of section 3(1) of the 2001 Act suggests that the intention of the Legislature was to make the 2001 Act compulsorily applicable to arbitration, including an international commercial arbitration that takes place in Bangladesh. Parties cannot by agreement override or exclude the non-derogable provisions of the 2001 Act in such arbitrations. However, section 3(1), does not imply that the provisions of the arbitration Act would not be applicable to arbitration proceedings taking place outside Bangladesh”.

(Underlines supplied)

(ii) The said single bench then, after elaborate discussion of the provisions of the UNCITRAL Model Law and some cases decided by the Indian Courts, in particular the Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA 2002 AIR (SC)-1432, held that Section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001 would be applicable in the proceedings where the seat of arbitration was in a foreign country. Accordingly, the said single bench stayed the admiralty suit concerned on an application filed by the defendants under Section 10 of the arbitration Act, 2001.

(b) Southern Solar Power Limited vs. PBDP, 25 BLC (2020)-501:

(i) Same point arose in this case as to whether the provisions of the arbitration Act 2001, in particular whether Section 7Ka (7A) of the arbitration Act 2001, would be applicable in view of the provisions under Section 3 of the said Act. The said single bench, presided over by his Lordship Mr. Justice Md. Khurshid Alam Sarker (exercising Special Original Jurisdiction), also took the trouble to examine all the previous decisions on this point and finally held that in the previous cases the implication of the provisions under Section 7A of the arbitration Act was not considered by examining the provisions under Section 3 and section 7A along with other provisions of the arbitration Act. This bench took a new approach in deciding the issues and finally held that because of the incorporation of the words in Section 7A, namely the words

the provisions of the arbitration Act would be applicable from the very beginning, before, during and after conclusion of the arbitration proceeding up to the implementation of the arbitration award. While discussing the scope of the said Act, as provided by Section 3, the said single bench, to some extent, took the approach taken in the above referred HRC Case and held as follows:

“36. From a minute reading of the marginal note and main provisions of Section 3 of the arbitration Act, it appears to me that this section is not about jurisdiction of the Courts. Section 3 of the arbitration Act makes a general statement about the ‘scope’ of application of the provisions of arbitration act. My humble understanding about the provisions in Section 3 of the arbitration Act is that since there is no prohibitory wordings to apply the provisions of the arbitration Act for the foreign arbitration and foreign arbitral tribunal nor is there any statement to the effect that the provisions of the arbitration Act shall ‘only’ be applicable in case of ‘international commercial arbitration’ taking place in Bangladesh the relevant provisions of the arbitration Act may be borrowed and applied by the foreign arbitral tribunal if the parties of the arbitration so agree. And our High Court Division may also apply the necessary provisions of the arbitration Act for the foreign arbitration such as, sections 7A and 10 in addition to the provisions of sections 45-47 of the arbitration Act. In other words, while ‘the foreign arbitration tribunal’ is free to observe, follow and apply our law, our High Court Division may use the relevant provisions of the arbitration Act, namely, sections 7A and 10 on top of applying the provisions of sections 45 to 47, in an arbitration which would take place or is being held in a foreign country, for, the wordings of Section 3 of the arbitration Act do not seek to oust the jurisdiction of the High Court Division in relation to an arbitration proceeding where the place of arbitration is outside Bangladesh.

(Underlines supplied)

(ii) By referring to the words

as occurring in Section 3(1) of the arbitration Act, 2001, the said single bench held as follows:

“37. The Legislature by engraving the word ‘scope’ in the marginal note of Section 3 of the arbitration Act sought to mean that while the provisions of this law shall be mandatorily applied to ‘domestic arbitration’, ‘international commercial arbitration’ which would take place in Bangladesh and execution of the award passed by the foreign arbitral tribunal as provided in sections 45, 46 & 47, the provisions of the arbitration Act may also be applied for foreign arbitration, if the parties to the foreign arbitration in their arbitration agreement makes such stipulation. Thus, clearly this section is about the ‘arbitration ‘, and it does not seek to state anything about the business or role of the ‘court’ as evident from the Bengali wordings ' (for the said ‘arbitration’) as occurs in Section 3 of the arbitration Act.”

(Underlines supplied)

(iii) The said single bench also examined the previous decisions of this Court in British Airways case, 17 BLD (AD)-249, HRC Shipping case, 12 MLR-265, KA Latif case, 13 BLC-457, Unicol Bangladesh case, 56 DLR (AD)-166, Uzbekistan Airways case, 10 BLC-614, and STX Corporation case, 64 DLR-550 and finally held that our Court decided those cases overlooking the scheme of the amendment of arbitration Act, 2001 on 24.01.2004 by which Section 7A was incorporated. The relevant paragraph in this regard is reproduced below;

“55. In all the referred cases of our jurisdiction, the interpretations (whether in favour of, or against, the application of the provisions of the arbitration Act in the foreign arbitration scenario) were apparently carried out by our Courts overlooking the scheme of amendment of the arbitration Act on 24.01.2004, by which Section 7A was incorporated in the arbitration Act. The most significant feature of Section 7A of the arbitration Act is that by coming in to effect on 19.02.2004, it removed the limited nature of applicability of the provisions of the arbitration Act, as was prevalent in section 7 of the arbitration Act, by heralding that the non-obstante clause of Section 7 of the arbitration Act would no longer be in operation. Given the status of section 7 of the arbitration Act that it is the provision by which jurisdiction of the Courts regarding arbitration matters have been conferred upon the Courts, albeit only for dealing with the limited issues, having dictated the Courts not to hear any case regarding arbitration, except for the causes enunciated in the arbitration Act, my view is that incorporation of section 7A in the arbitration Act by the Legislature on 24.01.2004 has obviously changed the jurisdictional footing of the Courts. More importantly, all the above-referred cases were decided without taking into consideration the expression “Notwithstanding anything contained in section 7 ………. until enforcement of the award under section 45……… the High Court Division……………may pass Order”, which is engraved in Section 7A(1) of the arbitration Act. Had it been the intention of the Legislature to keep the foreign arbitration out of the touch and grip of our Courts in dealing with injunction, preservation or any other necessary interim orders, the Legislature would not have incorporated the words “until enforcement of the foreign arbitral award”.

(Underlines supplied)

(iv) The said single bench, thereafter, declared the decisions in those cases as per incuriam in the following terms;

“56. In view of the fact that in all of the case-laws referred to by the parties of this case before me, the Hon’ble Judges of this Court did not have the opportunity to consider and examine the expressions “until enforcement of the foreign award” embodied in section 7A(1) of the arbitration Act, the aforesaid case-laws lack persuasive and authoritative power for binding this Court to apply the ratio laid down therein and, therefore, the said Judgments having been given per incuriam, this Court is not bound to apply the ratio laid down therein. When any Judgment is passed by any Court in ignorance of the applicable laws either because of forgetfulness of the Hon’ble author Judge or due to ill-information about the applicable laws by the learned Advocate/s or for not making the relevant laws available before the Court, the decision should be held to have been given per incuriam and, consequently, it would not have legal force to bind the Courts to follow and apply the ratio laid down therein”.

(Underlines supplied)

(v) The said single bench then gave summary of its opinion and finally concluded that the provisions of the arbitration Act 2001, in particular Section 7A, would be applicable even if the seat of arbitration was in a foreign country (see para-56 of the reported case).

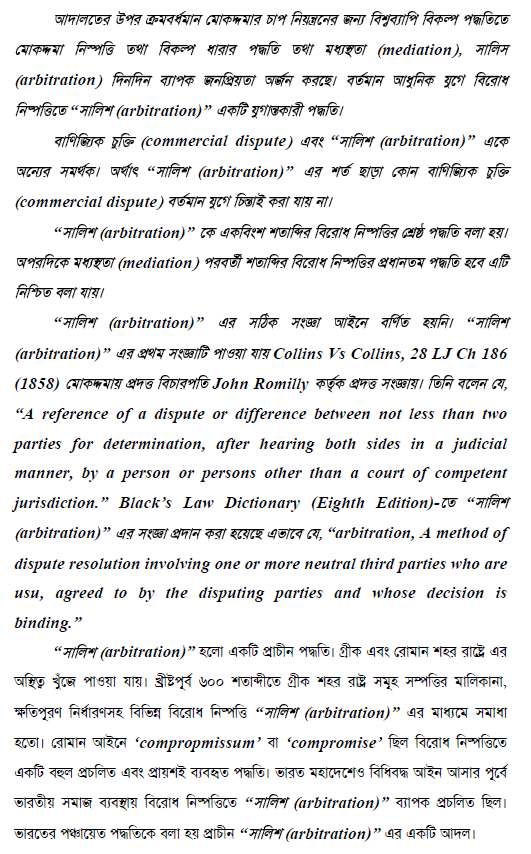

4.4. Before we deal with the above mentioned contrary views and the submissions of the learned advocates on the point of law involved, let us first give a short history of arbitration:

4.5. History of arbitration:

(a) Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) has religious sanctity in Islam as because its practice is originated from the Quran and was embraced from the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him). The idea of ADR is allowed in Islam except where it makes a thing ‘haram’ as ‘halal’ and ‘halal’ as ‘haram’. Al Quran says “If two parties among the believers fall into a quarrel, make ye peace between them …..with justice, and be fair; for Allah loves those who are fair and just” [Al Quran, Surah Al-Hujarat (49), Ayat 9]. Sulh, or conciliation and peacemaking, is a practice that even predated Islam. Within the framework of tribal Arab society, chieftains (sheikhs), soothsayers and healers (kuhhan), and influential noblemen played an indispensable role as arbiters in all disputes within the tribe or between rival tribes [See Hamidullah M., Administration of Justice in Early Islam (1937) 11 Islamic Culture, 163].

(b) As per Indian Mythology, in the dispute between Kauravas and Pandavas, Lord Krishna was chosen as the conciliator, as the mediator and ultimately the arbitrator. The village panch system in India is a classical example of deep rooted confidence on the chosen arbitrator. Normally the village headman or the panch parmeswar used to decide the disputes honestly and impartially (see Justice SB Malik, Commentary on the arbitration and Conciliation Act, Eighth Edition, Universal Law Publishing, Page-5).

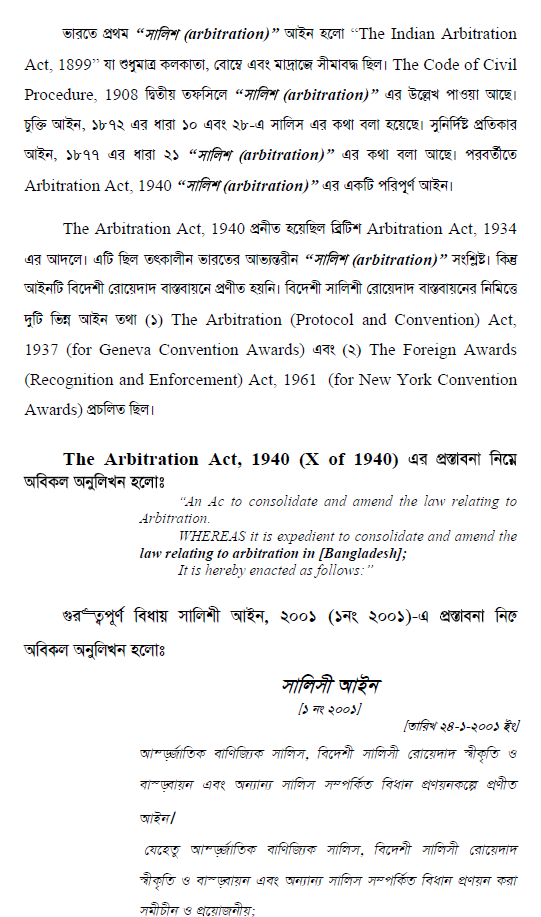

(c) The techniques of resolution of disputes by arbitration received legal recognition in India about two and a half centuries back. In 1772, for the first time, arbitration was introduced in India through the regulations framed by the East India Company under the authority vested in the company from the British Parliament, and such regulations authorized the Courts to refer the matters in dispute in a suit for decision by an arbitrator mutually acceptable to the parties. However, in the event of parties not consenting to appointment of an arbitrator by the Court, the dispute had to be tried by the Court itself. References to arbitration without the intervention of the Court became possible for the first time after enactment of Civil Procedure Code of 1859 (Act No. VIII of 1859) by which the civil procedure in Civil Courts and the law relating to it were codified for the first time in India (including present Bangladesh). Sections 312 to 327 of the said Code dealt with the arbitration in suits. The provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1859 were replaced by the Code of Civil Procedure, 1882 (Act No. XIV of 1882) and, later, by the present Code, namely the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (Act No. V of 1908). All the three codes recognised references of disputes to arbitration (see, in particular, Section 89B of the present Code as inserted by Act No. IV of 2003).

(d) Section 2(a) of the arbitration Act, 1899 gave recognition, for the first time, to the reference of disputes, likely to arise in future, to an arbitrator. A uniform law of arbitration applicable throughout India (including the present Bangladesh) was provided for the first time by the enactment of arbitration Act, 1940. After such enactment, various developments took place in international commercial world. One of such major changes was the formulation of a model law of arbitration, as adopted by the United Nations Commission for International Trade, which is known as ‘UNCITRAL Model Law on international commercial arbitration’. This model law highly influenced the countries in our subcontinent to formulate a new law in line with the same. Accordingly, our neighboring country, India, enacted the arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The very preamble of the said Indian Act specifically referred to the said UNCITRAL Model Law and, accordingly, enacted the said law incorporating therein provisions for recognizing and implementing international commercial arbitrations as well as foreign arbitral awards. Bangladesh has also enacted the arbitration Act, 2001 (upon repealing the 1940 Act) in line with the said UNCITRAL Model Law, with some deviations although. However, unlike Indian-law, it has not specifically mentioned, either in the preamble or in any other provisions, as regards formulation of the same in line with the said UNCITRAL model law.

Relevant provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001:

4.6. Although this appeal mainly relates to the interpretation of the provisions under Sections 3(1) and (2) of the said Act, such interpretation cannot be properly given without having a picture of the entire law before us, in particular the most relevant provisions of the said Act. Therefore, a small exercise may be done examining the said relevant provisions.

4.7. The preamble of the said Act provides that the said Act has been enacted in order for making provisions relating to the international commercial arbitration, recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award and other arbitrations. Therefore, it appears that the law has started its provisions with a flavor of internationality in the field of arbitration. The provisions of the said Act have been divided into 14 Chapters, each chapter dealing with separate issue. While the general provisions relating to the scope or applicability of the law, power of the Court to take ad-interim measures etc. have been grouped in Chapters 2 and 3, procedures to be adopted by the arbitration tribunals in arbitration proceedings, delivery of award and the effect of such award have been grouped under Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7. On the other hand, while Chapter 8 has grouped therein the provisions for cancellation of award, chapter 9 deals with the implementation of such award. Apart from above, the provisions under Chapter 10 have grouped therein the provisions as to the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award etc:

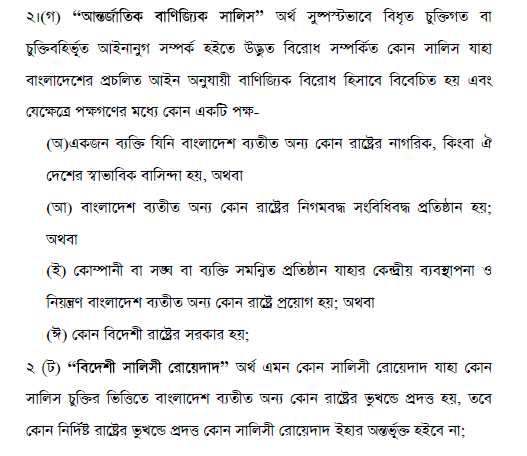

4.8. Before we examine any further, let us have an idea about the ‘international commercial arbitration’ and ‘foreign arbitral award’. Since the Legislature has specifically defined the said two terms, let us quote the same one after another:

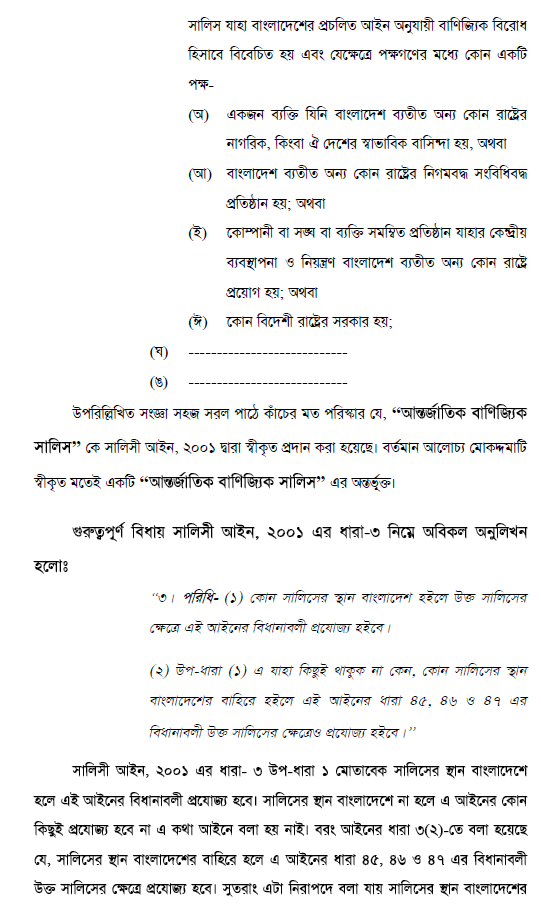

4.9. It appears from the above two definitions that when one of the parties in an arbitration agreement relating to commercial dispute is domiciled in a foreign country, that arbitration becomes international commercial arbitration. Such arbitration may take place in Bangladesh or in any foreign country. On the other hand, when, in accordance with the arbitration agreement, the arbitral award is given in a country except Bangladesh and not in a country specified under Section 47 of the said Act, such award becomes foreign arbitral award. As stated above, such awards are recognized and enforced as per the provisions incorporated under Chapter X of the said Act. Let us now examine, albeit in a cursory way, other relevant provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001.

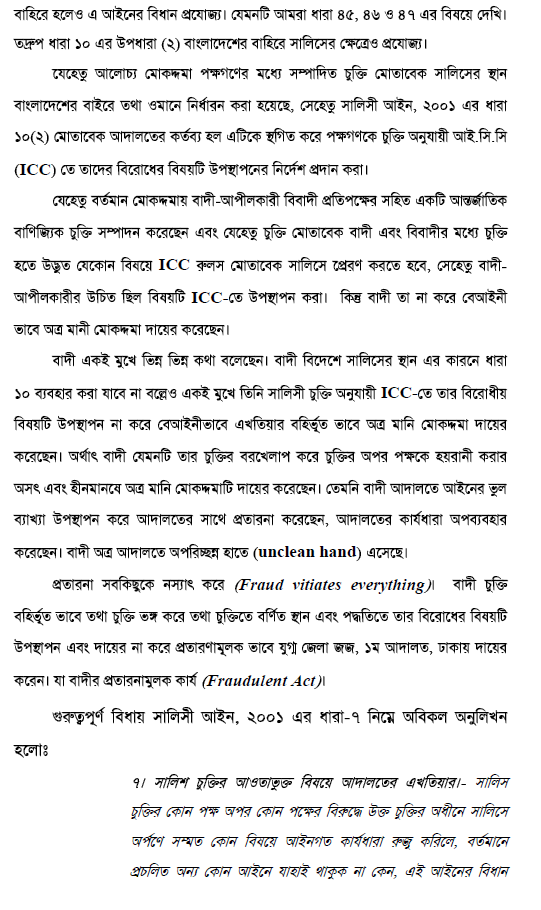

4.10. Section 3 of the arbitration Act, 2001 is the bone of contention between the parties in this appeal. However, we will deal with this provision elaborately later on. Suffice it to say now that this Section 3 has provided the ‘scope’ of the provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001. According to sub-section (1) of Section 3, the provisions of the arbitration Act shall apply where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. Sub-section (2), however, provides that notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the provisions under Section 45, 46 and 47 relating to the recognition and implementation of foreign arbitral award will also be applicable when the place of arbitration is outside Bangladesh.

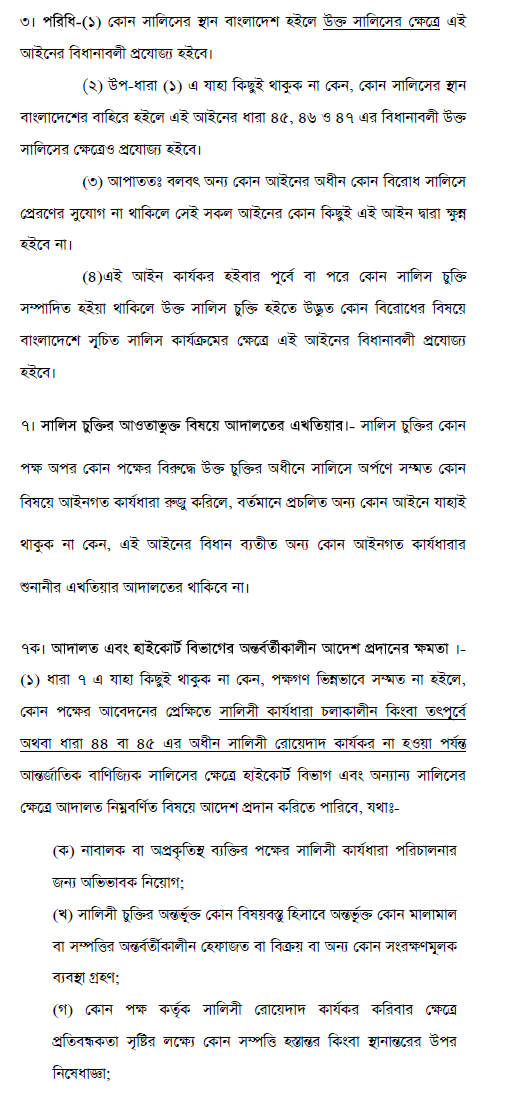

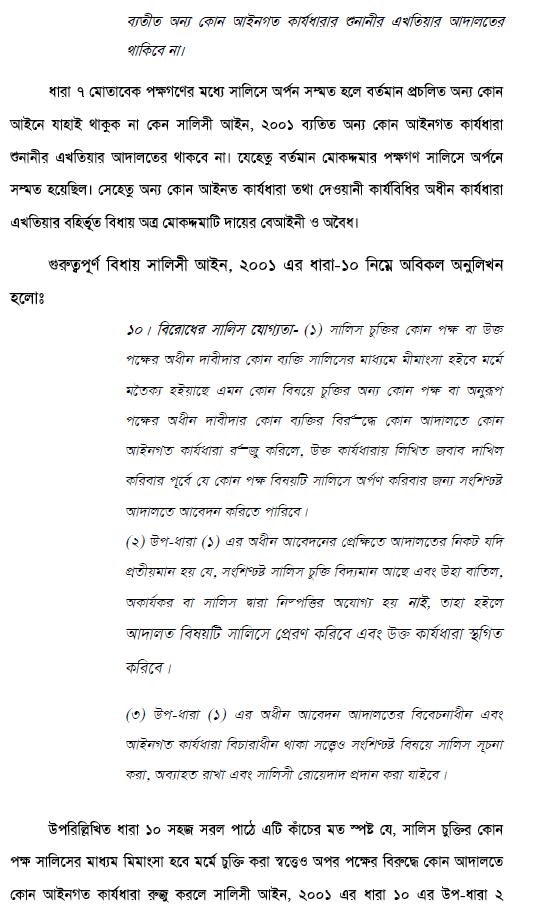

4.11. Section 7 of the said Act imposes a prohibition on the judicial authority in Bangladesh from hearing any legal proceedings except in so far as provided by the said Act when one of the parties to the arbitration initiates any legal proceedings before such judicial authority, and this provision has been given overriding effect over any other law for the time being in force by way of a non-obstante clause therein. Section 7Ka (or 7A), as incorporated subsequently by amendment in 2004, has conferred power on the judicial authority concerned to take interim measures for protection of the subject-matter of arbitration, notwithstanding anything contained in Section 7, and such ad-interim measures can be taken by such judicial authorities, on an application of a party to the arbitration agreement, during continuation of such arbitration proceedings or before or until enforcement of arbitral award under Sections 44 or 45 of the said Act. Besides, Section 10 of the said Act provides that the Courts concerned in Bangladesh shall refer the matter covered by arbitration agreement to arbitration and stay proceedings pending before it, on an application filed by any of the parties before filing written statement.

4.12. Apart from above, some other provisions, namely Sections 36, 39, 42 and 43 may also be looked into. While Section 36 provides that the parties shall have the liberty to choose the applicable law in an arbitration proceeding which shall be applied by the arbitral tribunal in adjudication of the dispute, Section 39 gives the finality of the arbitral award and a binding effect of the same on the parties to such arbitration with an exception to raise objections against such award in accordance with specific procedure on limited grounds as provided by Sections 42 and 43. Again, while Section 44 makes the provisions as regards enforcement of arbitral award like enforcement of a decree of civil Court in accordance with the Code of Civil Procedure, Sections 45 and 46 of the said Act recognize the foreign arbitral award given in foreign countries, except the specified countries as per Section 47, and that such award shall also be enforced like a decree of civil Court in the Court of District Judge, Dhaka and that enforcement of such award may only be refused if the same suffers from limited mischiefs as provided by Section 46.

Relevant Issues:

4.13. Since interpretation of the provisions under Section 3 is the main task in this appeal, let us now examine the said provisions in detail along with the provisions under Sections 7 and 7 Ka of the arbitration Act, 2001. Examination of Sections 7 and 7Ka has become relevant as because one of the single benches of the High Court Division in the above referred Southern Solar Case has expressed the view that by incorporation of the said provision under Section 7A in 2004, the limited nature of applicability of the provisions of the arbitration Act has been removed and that the Legislature has changed the jurisdictional footing of the Courts. Accordingly, the said provisions under Sections 3, 7 and 7Ka are reproduced below:

4.14. As stated above, Section 3 of the said Act has provided the scope or applicability of the provisions of the said Act. In specifying the said scope or applicability, sub-section (1) of Section 3 provides that where the place or Seat of any arbitration is in Bangladesh, the provisions of the said Act shall apply in respect of such arbitration. Sub-section (2), however, provides that notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47 of the said Act shall also be applicable to the arbitration if the place or seat of such arbitration is outside Bangladesh.

4.15. It may be noted at this juncture that although the Legislatures in India and Bangladesh have enacted their respective arbitration law following the guidelines given in the aforesaid UNCITRAL Model Law, they have not followed the same in toto. Such deviation by the Indian Legislation has been pointed out in more than one cases by the Indian Supreme Court [see for example, the decisions in Bhatia International (2002), 4 SCC-105, Venture Global Engg. (2008) 4 SCC-190 and Bharat Aluminum Co. Case (2012) 9 SCC-552]. Such deviation by our Legislature will also be apparent if we compare this provision under Section 3 with the corresponding provision of the UNCITRAL Model Law, namely Article 1 thereof. Sub-article (2) of Article-1 of UNCITRAL Model law is worded in the following terms:

“(2) The provisions of this law, except Articles 8, 9, 35 and 36, apply only if the place of arbitration is in the territory of this State”.

(Underline supplied)

4.16. It appears from the above quoted provision of the UNCITRAL Model Law that the said Model Law has specifically excluded the application of Article 8 (similar to our Section 10), Article 9 (similar to our Section 7A), Article 35 (similar to our Section 45) and Article 36 (similar to our Section 46) where the seat of arbitration is in the State concerned. Additionally, the word “only” has been used therein thereby providing the scope of applicability of the provisions of the said Model Law, except Articles 8, 9, 35 and 36, ‘only’ if the place of arbitration is in the territory of the State concerned. However, our Legislature has framed the said provision specifying the scope, namely Section 3, in a different way. Not only that the word ‘only’ has been omitted, our Legislature has also refrained from specifically excluding the application of the provisions under Sections 10, 7A, 45 and 46 when the seat of such arbitration is in Bangladesh. Similar scenario was there in the corresponding provision of law enacted by Indian Legislature before amendment in 2016 by their Act No. 3 of 2016. However, our Legislature has, under sub-section (1) of Section 3, made a legislative declaration to the effect that the provisions of the said Act shall be applicable when the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh. Again, according to sub-section (2) of Section 3, notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47 will be applicable even when the place of arbitration is in a foreign country. Therefore, it appears that although the word ‘only’ has not been used by our Legislature in sub-section (1) and that the applicability of the provisions under Sections 10, 7A, 45 and 46 have not been clearly excluded like the UNCITRAL Model Law (where the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh), it has, by sub-section (2), categorically stated that the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47, namely the provisions relating to the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award, will be applicable in respect of such arbitration where the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country. Therefore, by joint reading of these two provisions under sub-sections (1) and (2) of Section 3, it is clear that although the word ‘only’ has not been used by our Legislature, the impact of the said word is very much apparent when we see that our Legislature, by sub-section (2), has declared only three Sections, namely Sections 45, 46 and 47, which are applicable when the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country.

4.17. It is further clear from Articles 35 and 36 of the UNCITRAL Model Law that by such Articles, provisions have been modelled to recognize foreign arbitral awards and enforcement of such awards by competent Court in the State concerned. Therefore, it appears that when the UNCITRAL Model Law has clearly excluded the application of the provisions under Articles 8, 9, 35 and 36 in a case where seat of arbitration is in the State concerned, our Legislature has done the same thing in a different way in that it has mandated the applicability of the provisions of the said Act where the seat of arbitration is in Bangladesh, and, at the same time, by sub-section (2), it has declared that notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47 relating to the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award will be applicable in respect of an arbitration even if the seat of such arbitration is outside Bangladesh. Thus, the declaration given by our Legislature by way of the provisions under sub-sections (1) and (2) of Section 3 of the said Act is very much clear, which is that, the provisions of the arbitration Act will apply only when the seat of arbitration is in Bangladesh and that notwithstanding such provision, the provisions regarding recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral award are applicable in respect of an arbitration when the seat of such arbitration is in a foreign country. Therefore, we humbly cannot agree with the view expressed by the aforesaid two single benches of the High Court Division in the above referred HRC Shipping case (as expressed in paragraph-32 of the reported case as regards omission or absence of the word ‘only’) and Southern Solar Case (as expressed in paragraph-36 of the reported case). On the other hand, we are of the view that absence or omission of the word ‘only’ in sub-section (1) of Section 3 has been recuperated by the provisions under sub-section (2) of Section 3 of the said Act.

4.18. It may be noted that both the above mentioned single benches of the High Court Division in HRC Case and Southern Solar case have referred to the absence of the said word ‘only’ in our sub-section (1) of Section 3 and have reached a conclusion that by such absence of the word ‘only’, our Legislature has not expressly excluded the application of the provisions of the said Act in case of arbitration where the seat of such arbitration is in a foreign country. Probably, the said two benches have been influenced to reach such conclusion by the similar view as already expressed by the Indian Supreme Court in Bhatia International Case, (2002), 4 SCC-105. Although the decision in Southern Solar Case did not make any such reference to Bhatia International Case, the decision in HRC Shipping case has made such reference. However, it now appears that in the meantime the Indian Supreme Court, in Bharat Aluminium Com. vs. Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services Inc, (2012) 9 SCC-552 (in short BHALCO Case), has over-ruled the said decision in Bhatia International Case and another decision of Indian Supreme Court in Venture Global Engg. (2008) 4 SCC-190, which followed the ratio in Bhatia International Case. It may be mentioned that while the Bhatia Case was decided by three judges bench of the Indian Supreme Court, the BHALCO was decided by a constitutional bench comprising of five Judges of the Indian Supreme Court, and the said constitutional bench, in its judgment, delivered on 06.09.2012, over-ruled the decision in Bhatia International Case. Exactly same argument as regards absence of the word ‘only’ in the corresponding provisions of the Indian arbitration Act, namely Section 2(2) of the Indian arbitration Act, was made before the said constitutional bench by referring to the decisions in Bhatia International case and Venture Global case. However, the said constitutional bench of the Indian Supreme Court has answered the said argument in the following terms:

67. We are unable to accept the submission of the learned counsel for the appellants that the omission of the word “only” from Section 2(2) indicates that applicability of Part I of the arbitration Act, 1996 is not limited to the arbitrations that take place in India. We are also unable to accept that Section 2(2) would make Part I applicable even to arbitrations which take place outside India. In our opinion, a plain reading of Section 2(2) makes it clear that Part I is limited in its application to arbitrations which take place in India. We are in agreement with the submissions made by the learned counsel for the respondents, and the interveners in support of the respondents, that parliament by limiting the applicability of Part I to arbitrations which take place in India has expressed a legislative declaration. It has clearly given recognition to the territorial principle. Necessarily therefore, it has enacted that Part I of arbitration Act, 1996 applies to arbitrations having their place/seat in India.

(Underlines supplied)

4.19. Refuting the submissions made from the bar that the omission of the word ‘only’ in the said corresponding provision has nullified the territorial principle of the said Act, the said constitutional bench of the Indian Supreme Court has held as follows:

“It was felt necessary to include the word “only” in order to clarify that except for Articles 8, 9, 35 and 36 which could have extra-territorial effect if so legislated by the State, the other provisions would be applicable on a strict territorial basis. Therefore, the word “only” would have been necessary in case the provisions with regard to interim relief, etc. were to be retained in Section 2(2) which could have extra-territorial application. The Indian legislature, while adopting the Model Law, with some variations, did not include the exceptions motioned in Article 1(2) in the corresponding provisions Section 2(2). Therefore, the word “only” would have been superfluous as none of the exceptions were included in Section 2(2).

72. We are unable to accept the submission of the learned counsel for the appellants that the omission of the word “only”, would show that the arbitration Act, 1996 has not accepted the territorial principle. The scheme of the Act makes it abundantly clear that the territorial principle, accepted in the UNCITRAL Model Law, has been adopted by the arbitration Act, 1996”.

(Underlines supplied)

4.20. Not only that, in response to another argument from the bar that in case of non-applicability of the provisions relating to interim measures, the parties will be in a difficult position in protecting the subject matter of arbitration, the said constitutional bench has simply replied that it is the matter to be considered by the Legislature, not the Court. It may be noted that after the decision in BHALCO case by the said constitutional bench of the Indian Supreme Court, the Indian Legislature has in the meantime amended the corresponding sub-section (2) of Section 2 of their Act, thereby, incorporating a proviso thereto providing that some provisions including the provisions under Section 9 (our Section 7A) shall also apply to international commercial arbitration even if the place of such arbitration is out-side India. But no such amendment or legislation has been done by our Parliament in order to apply the provisions of the said Act in an arbitration where the seat of arbitration is outside Bangladesh. Therefore, since the Court cannot legislate, but may only declare the law as it is and interpret the law enacted by the Parliament, we cannot add anything to the provisions under sub-sections (1) and (2) of Section 3 of the said Act, as that will tantamount to legislation by the Court.

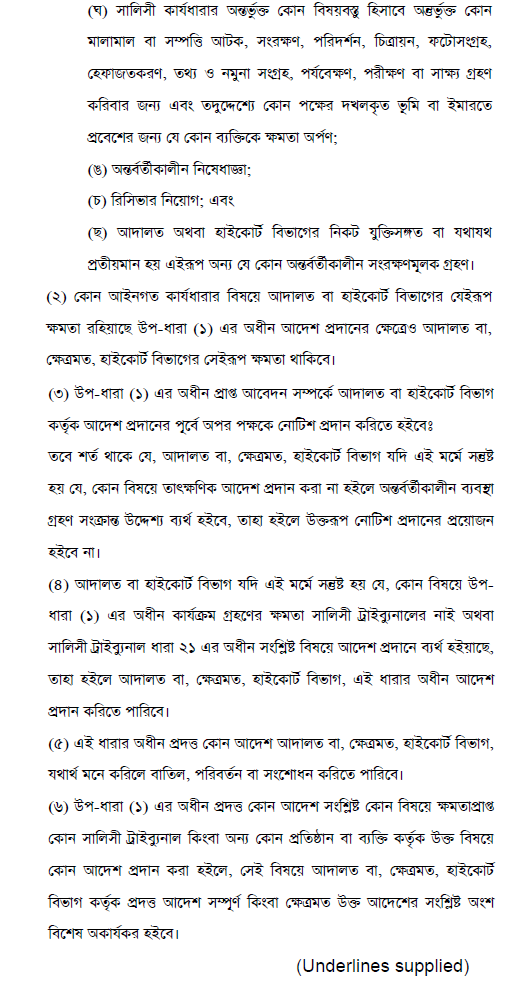

4.21. It may further be stated here that the words

as occurring in sub-section (1) of Section 3, refers to matters in respect of such arbitration when the place of arbitration is in Bangladesh, and such matters include the matters involving the proceedings before the Court in Bangladesh. Thus, the words

therein, under no circumstances, can be interpreted as referring to arbitration proceedings only, as held by a single bench of the High Court Division in the above referred Southern Solar Case [see paragraph 37 of the reported case]. When the Legislature enacts a provision thereby determining the scope of applicability of the provisions of a particular Act and when the words

are used in such provision declaring that the provisions of the said Act are applicable when the seat of such arbitration is in Bangladesh, the Legislature clearly means that the provisions of the said Act are applicable to matters relating such arbitration, be it in Court or before the arbitration Tribunal. Giving any different interpretation, in particular saying that by the words

the Legislature has only intended to apply the provisions of the said Act to ‘arbitration proceedings’ only and not matters relating to such arbitration, as held by the said single bench, will be a clear betrayal of the literal meaning of those words read in the context of other words used under the said sub-section (1) and other sub-sections. Therefore, we humbly cannot accept such interpretation. Accordingly, we have no option but to ignore the same.

4.22. Now, let us examine the provisions under Sections 7 and 7A of the said Act, in particular to examine what change, if any, has been brought-about by Section 7A to the scope of applicability of the provisions of the said Act. It appears from the provisions under Section 7 that by this provision the Legislature has determined the jurisdiction of the Court in respect of the matters covered by the arbitration agreement. Section 7 provides that notwithstanding anything contained in any other laws for the time being in force, if a party to an arbitration agreement initiates a legal proceeding in a Court in respect of matters covered by such arbitration agreement, the Court shall not have jurisdiction to hear any such proceeding which has not been initiated in accordance with the provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001. Therefore, it appears that by this provision the Legislature has only allowed the proceedings in a Court, by a party to an arbitration agreement, in respect of matters covered by arbitration which have been initiated in accordance with the provisions of the said Act and that the Court will not have jurisdiction to hear any proceedings in respect of such matters which have not been initiated or continued in accordance with such provisions of the said Act.

4.23. By incorporating Section 7A, as quoted above, in 2004 vide arbitration (Amendment) Act 2004 (Act No. 02 of 2004), with effect from 19.02.2004, the Legislature has conferred power on the High Court Division, in respect of International Commercial arbitration, and on the Court of District Judge concerned, in respect of other arbitrations, to take ad-interim measures by way of orders or ad-interim injunction etc. in order for preservation of the subject matters of the arbitration and such order can be passed, on the application of any party to the arbitration agreement, at different stages, namely during continuation of the arbitration proceedings or before or until enforcement of the arbitral award under Section 44 or 45 of the said Act. It may be noted that similar provision has been incorporated in the Indian arbitration Act, 1996 as Section 9, although it has been amended twice, once in 2015 and the other in 2016. However, the scope of application of the said provision under the Indian arbitration Act is almost similar to our provision under Section 7A which is evident through comparison.

4.24. Be that as it may, it appears from the examination of the above two provisions under Sections 7 and 7A of our arbitration Act that while Section 7 has ousted the jurisdiction of the Court in hearing any proceedings relating to the matters covered by the arbitration agreement if such proceedings are not in accordance with the provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001, Section 7A provides that notwithstanding anything contained in Section 7 as regards ouster of such jurisdiction of the Court, the Court shall have jurisdiction to take ad-interim measures in respect of matters covered by arbitration agreement, on the application of any of the parties to such agreement, at different stages, namely during continuation of the arbitration proceedings or before or until enforcement of the award under Sections 44 or 45 of the said Act. Therefore, this Section 7A appears to be an exception to Section 7 of the said Act in that while Section 7 ousts the jurisdiction of the Court to hear a proceeding in respect of the matters covered by the arbitration agreement if such proceeding is not in accordance with the provisions of the said Act, Section 7A provides an exception as regards interim measures in order for preservation of the subject-matter of arbitration, and the Court is empowered under this provision to pass ad-interim orders in order for such preservation during continuation of the arbitration proceedings, before such proceeding or until enforcement of the award under Sections 44 and 45.

4.25. This being so, while we agree with the observation made by the said single bench in Southern Solar case to the effect that by incorporation of this provision the jurisdictional footing of the Courts has been changed, we do not find any reason as to how the said provision has created any impact on Section 3. Rather, Section 7A provides that the Court shall have power to take ad-interim measures for the protection of the subject matter of arbitration, on an application of any party to such arbitration agreement, at three stages, namely during continuation of the arbitration proceedings or before or until enforcement of arbitral award. Therefore, the power of the Court to take ad-interim measures has been recognized until enforcement of local and foreign arbitral awards. Thus, we do not find any palpable reason as to why the said single bench has concluded that the Hon’ble Judges of this Court did not have the opportunity to consider and examine the expressions “until enforcement of foreign award” (sic.) as embodied in Section 7A(1) of the said Act, particularly when consideration or examination of such expressions were not at all material for determining the scope of the applicability of the provisions of the said Act in view of Section 3(1) and (2). This expression “until enforcement of the award under Section 44 or 45” has only provided the extent of the power of the Court as regards taking ad-interim measures, and by such expression, the Legislature has extended such power until enforcement of such award under Sections 44 or 45, as the case may be. In case of foreign arbitral award, such award needs to be enforced under Section 45 of the said Act. Once a foreign arbitral award is passed, such arbitral award is recognized and binding in Bangladesh, and the same is enforceable in Bangladesh like a decree of a Court in accordance with the provisions under the Code of Civil Procedure (“in the same manner as if it were a decree of the Court”). Thus, notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force, whenever such foreign award is filed along with an application before the Court of District Judge, Dhaka in accordance with the provisions under Section 45, the said Court shall have the power under Section 7A of the said Act to take ad-interim measures in respect for preservation of the subject matter of the arbitration until enforcement of the said foreign arbitral award.

4.26. It is pertinent to note that when Section 7A has ruled out the applicability of Section 7 by saying “notwithstanding anything contained in Section 7”, it has not ruled-out, in any way, the applicability of Section 3, sub-sections (1) and (2), by which the Legislature has declared the scope of applicability of the provisions of the said Act including Sections 7 and 7A. Therefore, until and unless the Legislature amends the provisions under Section 7A by incorporating the words ‘notwithstanding anything contained in Section 3’, the provisions under Section 7A cannot be invoked in respect of an arbitration where the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country, except at the stage of enforcement of foreign arbitral award. Because, such enforcement of foreign award has been accommodated by sub-section (2) of Section 3 itself by declaring that the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47 will be applicable even if the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country. This being the position through our extensive examination of the relevant provisions of law, in particular Section 7A along with the provisions under Section 3 of the said Act, we hold that the expressions, as occurring in sub-section (1) of Section 7A, namely the expressions “until enforcement of award under Sections 44 or 45”, do not in any way override the limited or territorial applicability of the provisions of the arbitration Act, 2001 as declared by Section 3, sub-sections (1) and (2), of the said Act. Thus, we have no option but to ignore the said decision of the said single bench of the High Court Division in Southern Solar case.

4.27. It may not be out of context to be reminded that Article 111 of our Constitution mandates that the law declared by the Appellate Division is binding on the High Court Division. Although it may not arguably be said in strict sense that the Appellate Division declared law by refusing to grant leave in the above referred Uzbekistan’s case in CPLA No. 1112 of 2005, it cannot be denied that the decision of a division bench of the High Court Division therein in respect of the applicability of Section 10 was approved by the Appellate Division. It is evident from the judgment of the Appellate Division in the said Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal No. 1112 of 2005 that the judgment therein was authored by the then Hon’ble Chief Justice of Bangladesh, Mr. Justice Md. Ruhul Amin. The other two hon’ble Judges of the Appellate Division in the said case have, in the meantime, adorned the office of the Chief Justice of Bangladesh. The Appellate Division, in the said judgment, even reproduced the observations of the High Court Division in Uzbekistan case and finally held that it did not find any reason to interfere with the said judgment and order of the High Court Division. Even if we put aside the argument whether the said decision could be regarded as a law declared by the Appellate Division in view of the provisions under Article 111 read with Article 103 of the Constitution, it cannot be denied that by the said judgment the Hon’ble Judges of the Appellate Division expressed their mind as regards applicability of the provisions under Section 10 of the said Act by approving the decision of the High Court Division even by reproducing the relevant paragraphs from the judgment of the High Court Division. Therefore, we are of the view that for the sake of maintaining judicial discipline, no bench of the High Court Division, irrespective of its strength in terms of number of Judges, should defy such view of law as expressed by the said Hon’ble Judges of the Appellate Division. Terming such a decision of the Hon’ble Appellate Division as per incuriam is an unimaginable course. In this regard, we are reproducing some observations of our Appellate Division in BADC vs. Abdul Barek Dewan and others, 19 BLD (AD) (1999)-106 (see para-17):

……………………………. The reasoning given by the High Court Division was first that it did not agree with the decision of this court and secondly that the decision was given “per incuriam”. The criticism offered by the learned Judges of the High Court Division betrays their lack of knowledge about the doctrine of ‘per incuriam’ and article 111 of the Constitution.

The word “per incuriam” is a Latin expression. It means through inadvertence. A decision can be said generally to be given per incuriam when the court had acted in ignorance of a previous decision of its own or when the High Court Division had acted in ignorance of a decision of the Appellate Division. [see, Punjab Land Development and Reclamation Corporation Ltd. vs. Presiding Officer, Labour Court, 1990 (3) SCC 685 (705)]. Nothing could be shown that the Appellate Division in deciding the said case had over looked any of its earlier decision on the point. So it was not open to the High Court Division to describe it as one given “per incuriam’. Even if it were so, it could not have been ignored by the High Court Division in view of Article 111 of the Constitution which embodies, as a rule of law, the doctrine of precedent.

Apart from the provision of Article 111 of the Constitution enjoining upon all courts below to obey the law laid down by this Court, judicial discipline requires that the High Court Division should follow the decision of the Appellate Division and that it is necessary for the lower tiers of courts to accept the decision of the higher tiers as a binding precedent. This view was poignantly highlighted in Cassell & Co. Ltd. Vs. Broome and another, (1972) AC 1027 where Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone, the Lord Chancellor in his judgment said:

‘The fact is, and I hope it will never be necessary to say so again, that, in the hierarchical system of courts which exists in this country, it is necessary for each lower tier, including the Court of Appeal, to accept loyally the decisions of the higher tiers.’

(Underlines supplied)

4.28. The observations of the Appellate Division regarding the power of the single bench and division bench of the High Court Division, as given in Taehung Packaging (BD) Ltd. & others. vs. Bangladesh and others. 33 BLD (AD) 2013-359, may also be looked into (see paragraphs 12 and 13 of the reported case).

4.29. In view of above, we have no option but to hold that the provisions of the arbitration Act 2001, except the provisions under Sections 45, 46 and 47, are not applicable in respect of an arbitration where the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country. However, the provisions under Section 7A, for taking ad-interim measures, may be invoked in respect of foreign arbitral award only when application for enforcement of such award is filed before the Court of District Judge, Dhaka in view of the provisions under Section 45 of the said Act and such ad-interim measures may be taken till such award is enforced.

Inherent Power of the Court:

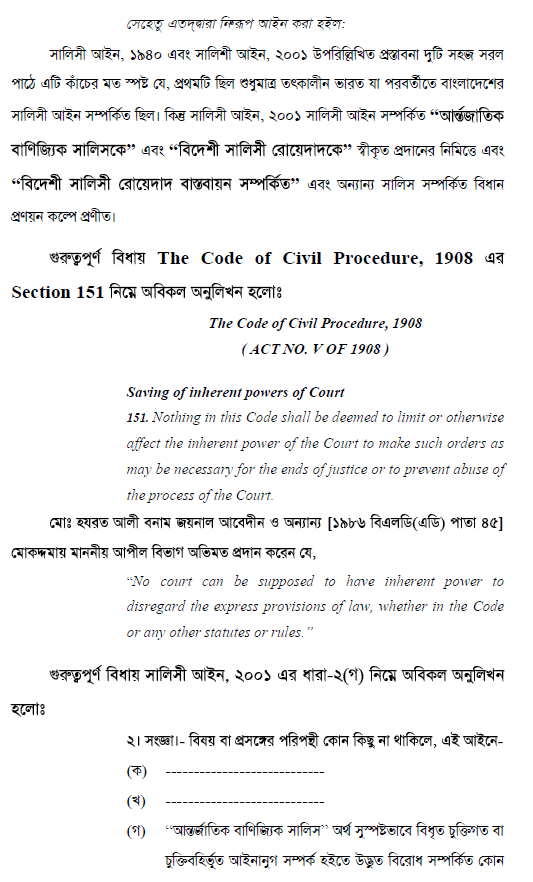

4.30 Now the question is, in the absence of such provision to stay proceedings under Section 10 of the said Act, whether the Court may excise it’s inherent power to stay such proceedings. Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure provides that nothing in the Code shall be deemed to limit or otherwise affect the inherent power of the Court to make such orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice or to prevent abuse of the process of the Court. Therefore, it is apparent from this provision that this provision is not affected by any other provisions of the Code and that any other provision of the Code shall not be deemed to limit or affect the inherent power of the Court when the occasion arises to pass such necessary order for ends of justice or to prevent the abuse of the process of the Court.

4.31 On this point, we have examined the decisions referred to by the learned advocates, namely the decisions in Md. Hazrat Ali’s Case, 1986 BLD (AD)-45 and Abdul Mohit’s Case, 61 DLR (AD)-82, as cited by the learned advocate Mr. Azim, along with the decisions cited by Mr. Probir Neogi, learned senior counsel (as Amicus Curiae), namely the decisions in Ayat Ali’s Case, 40 DLR (1988)-56 and in Annamalay Case, AIR 1931, Privy Council-263. It appears from the above referred Hazrat Ali’s case that in the said case the subordinate judge concerned convicted and sentenced the appellant therein to suffer two months simple imprisonment in civil prison in a proceeding filed by respondent No. 1 under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure alleging defiance of the Court order to deposit the attached money. In the said case, our Appellate Division held that such conviction and sentence could not be imposed under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure when there were specific provisions in the Code, namely Order 39, rule 2(3), and Contempt of Court Act. Therefore, it appears that in the said case, exercise of inherent power of the Court was not approved by the Appellate Division when specific enactment like Contempt of Court Act or provisions like Order 39, rule 2(3) of the Code for imposing such punishments were available.

4.32 Again, in Abdul Mohit’s case, the company bench of the High Court Division dismissed the company matter holding the same to be not maintainable in the company Court thereby rejecting an application filed by the appellant seeking direction upon the respondents to serve notice of board meeting to the appellant-directors in compliance with Section 95 of the Companies Act, 1994 to enable the appellants to attend the meeting of the board of directors of the respondent No. 1-bank. As against this scenario, leave was granted to consider whether the company Court was entitled to exercise its inherent jurisdiction, where there were manifest breach of law and articles, to prevent injustice. The Appellate Division therein dismissed the appeal by referring to Section 9 of the Code of Civil Procedure holding thereby that Section 95 of the Companies Act does not provide any forum. Therefore, any dispute arising there-from has to be resolved by the Civil Court and as such the inherent jurisdiction under the Companies Act, in the absence of any specific provision therein, could not be invoked to enforce the provision of Section 95 of the Companies Act as the said provision was providing procedural matters only and was not a substantive provision.

4.33 Therefore, it appears that in the first case, namely in Hazrat Ali’s case, there were specific provisions under the Code of Civil Procedure and Contempt of Court Act to impose punishment on the appellant. Therefore, it was held by the Appellate Division that in presence of such specific provisions for punishing a delinquent party in a suit, such delinquent party could not be punished in exercise of inherent power of the Court under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure. On the other hand, in Abdul Mohit’s case, Section 95 of the Companies Act did not provide any specific forum for the company bench. Rather, it was a procedural matter as regards issuance of notice on the directors. Therefore, when the specific forum was absent under Section 95, it was held that the company bench was not entitled to enforce the said provision under Section 95 in the garb of exercising inherent power under Section 151 of the Code. Thus, it was held therein that the remedy lied with the Civil Court under Section 9 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

4.34 As against above decisions of our Appellate Division, if we examine the case in hand along with the view already taken by us to the effect that the provision under Section 10 will not apply in respect of an arbitration where the seat of arbitration is in a foreign country, the question of existence of Section 10, or the Courts power to invoke Section 10 of the arbitration Act, does not arise at all. Therefore, the ratio decided in those cases do not have any manner of application in the facts and circumstances of the present case. However, the ratio in the above referred Ayat Ali’s case, where instead of staying proceeding of subsequent suit under Section 10 of the Code of Civil Procedure, the Court was allowed to dispose of both the suits simultaneously in exercise of its power under Section 151 of the Code, seems to be more relevant in the facts and circumstance of the present case. In the said Ayat Ali’s case, in spite of the presence of the mandatory provisions of Section 10 of the Code to stay subsequent suit between the same parties, the High Court Division allowed simultaneous hearing of both the suits in exercise of inherent power of the Civil Courts under Section 151 of the Code to secure ends of justice.

4.35 Now, the question is whether the Court in our case should have stayed the proceedings pending before it in exercise of such inherent power of the Court for sending the matter in dispute to resolve through arbitration. As stated above, admittedly, the parties have agreed through the said two agreements, namely the GSA and GSSA agreements, to settle their dispute through arbitration. Not only that, Clause 30 of the said agreements stipulates that such disputes shall be referred and settled by arbitration under the Rules of Conciliation and arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce. Clause 30.4 further stipulates that the decision of the arbitration panel shall be enforceable by the Courts of Sultanate of Oman. Not only that, according to Clause 40.2 of the said Agreements, the parties have agreed that their agreements would be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the Sultanate of Oman and that Courts in Oman shall have the exclusive jurisdiction. Therefore, it appears that, by these agreements, the parties have not only agreed to resolve their disputes through arbitration in Oman, they have also agreed that their agreements shall be governed and construed in accordance with the law of Oman and that the Court in Oman shall have exclusive jurisdiction. Thus, the parties agreed to oust the jurisdiction of the Courts in Bangladesh.

4.36 Admittedly, one of the parties to the agreements is domiciled in Bangladesh and another party in Oman. Therefore, both the Courts in Bangladesh and the Courts in Oman have jurisdiction over the matter. But the parties have agreed to choose one of the jurisdictions by ousting the other, namely they have agreed to oust the jurisdiction of Bangladesh Courts in favour of the jurisdiction of Oman Courts. This type of agreement ousting the jurisdiction of the Courts of one place in favour of the jurisdiction of the Courts in another place by way of arbitration agreement fall under the Exception 1 to Section 28 of the Contract Act, 1872 and, accordingly, such contracts are valid contracts. This position has been settled by our Courts and the Courts in India in more than one cases. See for example, the above referred M.A. Chowdhury vs. M/s. Mitsui, 22 DLR (SC) (1970)-334, Bangladesh Air Service (Pvt.) Ltd. vs. British Airways PLC, 17 BLD (AD)(1997)-249, A.B.C. Laminart Pvt. Ltd. vs. A.P. Agencies, AIR 1989 (SC)-1239 and M/s. L.T. Societa vs. M/s. Lakshminarayan, AIR 1959 Calcutta-669). Relevant observation of the then Supreme Court of Pakistan in the said M.A. Chowdhury’s case may be quoted below: