IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH (HIGH COURT DIVISION)

arbitration Application No. 5 of 2018

Decided On: 25.11.2018

Appellants: Corona Fashion Limited

Vs.

Respondent: Milestone Clothing Resources LLC and Ors.

**Hon’ble Judges:**Muhammad Khurshid Alam Sarkar, J.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Syed Mohidul Kabir, Advocate

For Respondents/Defendant: Ahsanul Karim, Advocate

Subject: Import/Export

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

**Acts/Rules/Orders:**Contract Act, 1872 - Section 23

Citing Reference:

Discussed

7

Mentioned

1

JUDGMENT

Muhammad Khurshid Alam Sarkar, J.

-

At the instance of the petitioner, this application has been filed under section 12(3) a(ii) of the arbitration Act, 2001 (hereinafter referred to as the arbitration Act) calling upon the opposite party Nos. 1 and 2 to show cause as to why an arbitrator shall not be appointed from their side for resolution of the dispute between the parties.

-

The fact of the case, briefly, is that the petitioner is a private limited company incorporated under the Companies Act, 1994 (henceforth referred to as the Companies Act) with incorporation certificate No. C-43512(52)2001. The petitioner-company is engaged in manufacturing garments of all kinds in Bangladesh and in exporting its products abroad. On 16-1-2015, the petitioner-company received a Letter of Credit (L/C) being No. FIMOLUA 1500-90001, total Value US$ 405,731.20; one amount is US$ 365,731.20 which was received on 16-1-2015 and the other amount is US $ 40,000 which was received on 24-6-2015 under a purchase order No. 1001 from Milestone Clothing Resources LLC, an American company (hereinafter referred to either as the importer or the respondent No. 1 or the Milestone) via Coreattire Fashion Ltd (respondent No. 6) who is the local agent of respondent No. 1 and in whose favour the L/C was initially opened and, subsequently, who (respondent No. 6) transferred the L/C in favour of the petitioner-company. Between 15-9-2015 to 20-10-2015, the petitioner-company made all together 3 (three) exports to the importer and got payment against the aforesaid exports. On 29-6-2016, the petitioner-company made export under invoice No. CFL/EXP/ MCI/026/16 dated 29-6-2016 to the importer amounting to $85,685.45, but the payment was refused by the importer’s bank on 5-2-2017 on the ground of late shipment, non-amendment of respective L/C and late presentation of the documents. After exchanging a few communications, finally, the aforesaid export bill was refused in clearer terms by the importer’s bank in accordance with Article 16(e) of UCP 600.

-

Thereafter, the importer made a request to the petitioner through e-mail on 25-2-2017 for sending a self-same export documents under URC-522 to Wells Fargo Bank NA, USA (hereinafter referred to as the Wells Fargo Bank or the opposite party No. 2) under a discounted rate of 20%, by reducing the total value to US $ 68,527.04, and promised to release the documents under drawers acceptance (D/A) subject to URC-522. The petitioner-company agreed to the proposal and sent an advice to the Wells Fargo Bank with a request to accept the drawer acceptance upon giving at-sight payment maturity date of 90 days period in accordance with URC-522 from the importer and accordingly the petitioner-company sent a same set of export documents being Invoice No. CFL/EXP/MCI/ 026/16 dated 29-6-2016 under House Bill of lading being No. NGL 1607081 dated 15-6-2016, port of destination Los Angels, USA to the address of the importer for immediate release of exported goods which were being held by the USA customs authority for want of valid export documents. Subsequently, the exports were released by the importer upon signing a drawer acceptance letter (D/A) under URC-522 before the Wells Fargo Bank.

-

As the drawer acceptance expired on 30-6-2017, the petitioner-company made several requests to the importer for payment and eventually, when, on 15-7-2017, the importer came to Dhaka, the petitioner-company demanded the payment, but the importer persisted in avoiding the payment. Under the circumstances, the petitioner-company issued a legal notice on 5-10-2017 to the importer and the Wells Fargo Bank for making the aforesaid payment. On 14-11-2017, Wells Fargo Bank replied through their legal department having admitted the transaction ref. No. UNI 499832, but declined to make the payment.

-

On 10th January, 2018 the petitioner-company through its lawyer issued a notice under section 27 of the arbitration Act for invoking arbitration. On 10th February 2018, the Wells Fargo Bank, in reply to the notice for invoking arbitration, categorically declined to send the instant matter to arbitration. Only pro-forma respondent No. 6 (Coreattire Fashion, who had acted as the country representative of the importer) consented to the arbitration. Under the circumstances, the petitioner-company approached this Court for appointment of an arbitrator on behalf of Wells Fargo Bank and, upon a preliminary hearing, this application was admitted and show cause notices were issued upon the respondents.

-

Wells Fargo Bank (respondent No. 2) contested this Rule by filing an affidavit-in-opposition contending, inter alia, that the respondent No. 2 acted for its customer, Milestone Clothing Resources LLC (importer/respondent No. 1), as a bank for facilitating a “Documentary Collection” transaction with the petitioner-company. The “Documentary Collection” transaction was handled according to the Uniform Rules for Collection, International Chamber of Commerce Publication No. 522 (“URC 522”). Wells Fargo Bank acted in the transaction as the collecting bank and presenting bank, under collection instructions of the remitting bank, i.e. Brac Bank Limited (respondent No. 4). Brac Bank authorised Wells Fargo Bank to handle documents on a collection basis and to release documents to the importer upon receipt of Milestone’s letter of undertaking to pay the collection amount in 90 days. Wells Fargo Bank duly carried out its obligations in such capacity and released the documents to the importer after receiving their signed letter of undertaking. But Wells Fargo Bank did not receive any payment from the importer. If the importer does not honour the letter of undertaking, Wells Fargo Bank does not have any obligation under the URC 522 to make any payment to the exporter (petitioner-company). If the petitioner-company was to recover any payment, they should initiate proceedings against Milestone. Wells Fargo Bank did not, and does not, have any contractual relationship with the petitioner-company, let alone an arbitration agreement. Nowhere in this application has it been stated that there was an arbitration agreement between the petitioner-company and Wells Fargo Bank. It is stated that upon receipt of the so-called notice of arbitration dated 10-1-2018, Wells Fargo Bank issued a reply dated 10-2-2018 stating clearly that the said “notice of arbitration” would be disregarded by Wells Fargo Bank, inasmuch as there was no arbitration agreement between the parties.

-

Mr. Syed Mohidul Kabir, the learned Advocate appearing for the petitioner-company, takes me through the e-mail sent by the importer-company on 24-2-2017 and submits that this Court should construe this piece of e-Mail communication as a clear ‘proposal’ from the importer to give security of this “Documentary Collection” and the remitting Bank’s (the Brac Bank-respondent No. 4) letter dated 30-3-2017 and the commercial document dated 22-3-2017 issued by the advising Bank (Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited) are to be taken by this Court as the ‘acceptance’ to the importer’s proposal and the letter of undertaking given by the importer to the Wells Fargo Bank is the “consideration” and, that is how, a contract was established between the petitioner-company and the importer together with his Bank (Wells Fargo Bank).

-

He refers to Article 9 of the URC-522 and submits that since Wells Fargo Bank, as the collecting Bank, has given a maturity date in the Bill of Exchange under URC-522 as 90 days deferred payment and delivered the commercial documents to the importer, the collecting Bank is under an obligation to act in good faith and exercise reasonable care. In this case, Wells Fargo Bank having not taken any measure for collection of Bill of Exchange did not discharge its duty with due diligence. In an effort to strengthen his above count of submission, he refers to the case of North Am. Stainless vs. PNC Bank Kentucky, Inc., No. 99-5730, 2000 WL 1256898 US Appeal Lexis-6th Cir. Jul, 13, 2000 and submits that in the aforecited case it was observed that “Although URC-522 does not address the consequences of a bank’s failure to use such care, a party claiming a breach of that duty must prove that the breach was the proximate cause of its injury”.

-

Then he submits that Unified Commercial Code (UCC) is the law of United States of America for handling documentary drafts for presenting and notifying customers of dishonor, and referring this Court to sections 3-115, 3-407 and 4-501 of UCC he submits that in the instant “Documentary Collection”, since there is evidently a contract, the arbitral tribunal should examine through adducing evidence as to whether the Wells Fargo Bank took collateral security from the drawee and whether the petitioner’s banks (advising bank & remitting bank) have failed to claim money in due time after maturity of Bill of Exchange.

-

Then, he takes me through the letter dated 5-10-2017 written by the petitioner-company to the Wells Fargo Bank together with the letter dated 14-11-2017 written by the Wells Fargo Bank to the petitioner-company and, side-by-side, places before this Court the provisions of section 9 of the arbitration Act and submits that, from the very beginning, the petitioner has considered the said “Documentary Collection” as a contract between the respondents and the petitioner. As per the ISBP (International Standard Banking Practice, approved by ICC in 2002) Rule, it is an electronic transmission and, thus, it may be presumed that the document is duly signed by the parties, he argues. He submits that for the aforesaid reasons this Court should construe that this documentary transaction is signed by the parties.

-

He, then, places Preambles of arbitration Act of 2001 & arbitration Act of 1940 and section 2(c) of arbitration Act of 2001 and submits that the object and scheme of enactment of arbitration Act of 2001, upon repealing the arbitration Act of 1940, is to facilitate holding of arbitration of international commercial disputes in the Bangladesh territory and, also, to execute the foreign arbitration award in Bangladesh. He submits that since the dispute between the parties is an international commercial dispute, this Court should send this matter to the arbitral tribunal. He contends that in the letter dated 14-11-2017, Wells Fargo Bank suggested that this petitioner files a suit in the USA-Court, but this petitioner should not be compelled to spend a huge amount of money in contesting a suit in the USA when the dispute clearly falls within the definition of “international commercial dispute” under section 2(c) of the arbitration Act. He argues that if an arbitrator is not appointed on behalf of the Wells Fargo Bank, this petitioner, being financially unable to contest the suit in the USA, shall be without remedy.

-

By taking me through the provisions of section 17 of the arbitration Act, the learned Advocate for the petitioner-company strenuously argues that it is for the arbitral tribunal to examine whether there is existence of any arbitration agreement. In this connection the learned Advocate refers to the case of Md. Hazrat Ali vs. Joynul Abedin 1986 BLD (AD) 45 wherein it was held that “no Court can be supposed to have inherent power to disregard express provisions of law wherever they exist” and submits that in the backdrop of operation of section 17(a) of the arbitration Act, which expressly makes provision for examination of the issue as to whether there is existence of any arbitration agreement, the aforesaid issue shall be examined by the arbitral tribunal and, therefore, this Court should refrain from examining the same. He strenuously argues that if this petitioner-company fails to satisfy the arbitral tribunal as to existence of any arbitration agreement, the arbitration application will be rejected at the peril of the petitioner-company, for the arbitration tribunal usually passes order of appropriate costs if an arbitration application fails. He submits that since the respondent No. 2 is not going to suffer any loss in any manner, this Court should exercise its discretionary power in sending this matter to the arbitral tribunal, in the event that this Court does not find a specific provision in the arbitration Act for sending this case thereto. Lastly, he takes me through section 20 of the arbitration Act and submits that without filing an application for determining the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal, before this Court, the respondent No. 2 cannot seek adjudication of this issue from this Court.

-

By making the above submissions, the learned Advocate for the petitioner prays for appointment of an arbitrator on behalf of Wells Fargo Bank towards formation of an arbitral tribunal.

-

Dr. Sharif Bhuiyan, the learned Advocate appearing for the respondent No. 2 (Wells Fargo Bank), takes me through all the papers annexed to this petition and submits that between the petitioner-company and the respondent No. 2, there is no contractual relationship, let alone the arbitration agreement.

-

By taking me through Chapter 3 of “Law and Practice of International Commercial Arbitration”, a text-book on international arbitration published by Sweet & Maxwell, he submits that if there is no written contract between the parties, there cannot be any arbitration agreement. He submits that in the absence of having any arbitration agreement, if this Court constitutes an arbitral tribunal, then there will be an anarchy in the administration of justice in the civil jurisdiction.

-

Upon dwelling on the letter dated 5-10-2017 sent by the petitioner-company to Wells Fargo Bank and the reply thereto dated 14-11-2017 by Wells Fargo Bank, Dr. Bhuiyan submits that the petitioner-company’s aforesaid letter is merely a legal notice upon the Wells Fargo Bank for making payment to the petitioner-company or, in the alternative, to appoint an arbitrator. Prior to sending the said legal notice, there was no existence of any contract between the petitioner-company and Wells Fargo Bank and, therefore, in absence of privity of contract between the parties, there cannot be any proposal of arbitration from the side of the petitioner-company and, accordingly, Wells Fargo has disregarded the proposal of arbitration, Dr. Bhuiyan continues to submit. In this connection, he places the provisions of section 9 of the arbitration Act and submits that the learned Advocate for the petitioner is misreading and misconstruing the aforesaid provisions of law. He submits that the present application is a misconceived one and hence the same is not maintainable.

-

With regard to the submissions advanced by the learned Advocate for the petitioner-company on the provisions of section 17 of the arbitration Act, Dr. Bhuiyan submits that the arbitral tribunal becomes competent to examine the issue as to whether or not there is existence of a valid arbitration agreement-only when a tribunal is formed on the consent of the parties to agreement. He argues that since, in this case, one party is not consenting to the formation of arbitral tribunal on the ground of non-existence of any contractual relationship between the parties, the above submission is based on misconception of the application of the provisions of section 17 of the arbitration Act. He submits that it is an absurd proposition that, without examining the existence of any arbitration agreement, this Court would simply refer the matter to the arbitral tribunal upon making appointment of an arbitrator. In an effort to buttress up his above submissions, he places before me the provisions of sections 11 & 16 of the Indian arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996 and submits that provisions of sections 12 & 17 of our arbitration Act correspond to the provisions of sections 11 & 16 respectively of the Indian arbitration Act and sub-section 6A of section 11 of the Indian arbitration Act makes it mandatory for the Court to examine the issue of “existence of an arbitration agreement”. In support of his submissions, he refers to the case of Mohammed Enamul Huq vs. Government of Bangladesh 23 BLT 542 and a catena of cases of the Indian jurisdiction.

-

By putting forward the above submissions, the learned Advocate for the respondent No. 2 prays for discharging the Rule with exemplary costs.

-

Mr. Ahsanul Karim, the learned amicus curiae, presents a very useful and impressive written skeleton before this Court. His opinions, briefly, are that the correspondences between the lawyer of the petitioner-company and Wells Fargo Bank do not constitute a contract; secondly, the legal notice sent to the Wells Fargo Bank by the petitioner-company’s lawyer dated 5-10-2017 and Wells Fargo Bank’s reply dated 14-11-2017 do not attract the provisions of section 9(2)(b) & (c) of the arbitration Act; thirdly, the ratio laid down in the case of Mohammed Enamul Huq vs. Government of Bangladesh 23 BLT 542 is applicable in this case; fourthly, Wells Fargo Bank, as a collecting and presenting Bank, is not under any obligation to take collateral security towards securing the deferred payment (D/A) at the time of releasing the documents to the drawee (importer) and, finally, though there is a practice in global Banking to incorporate the provisions of arbitration in dealing with L/C, D/P, D/A however, in this case, the concerned Banks (remitting Bank and the collecting Bank) not having incorporated the arbitration clause in their initial contract, cannot now go for arbitration and it is his opinion that the petitioner-company’s remedy lies in the civil Court, which may be of either of USA or Bangladesh. In formulating his opinion, Mr. Karim has referred to scores of case-laws of our jurisdiction and that of Indian & English jurisdictions in addition to furnishing the relevant laws in a binding form.

-

Upon hearing the learned Advocate for the petitioner-company, the learned Advocate for the respondent No. 2 (Wells Fargo Bank), the learned Advocates for the respondent Nos. 3 & 5, the learned amicus curiae, on perusal of the petitioner’s application together with its annexures as well as the affidavits filed by the respondents and having read the relevant laws and citations, I find that the first and foremost, point to be investigated is (i) whether this Court is competent to examine the existence of any agreement of arbitration between the parties. If the answer is found in the affirmative, then the following issues are to be examined by this Court towards an effective adjudication of this case, (ii) whether there is any contractual relationship between the petitioner-company and the collecting Bank (Wells Fargo Bank), (iii) whether the legal notice sent by the petitioner’s lawyer to the collecting Bank and the reply thereto by the collecting Bank compose an implied form of arbitration agreement under the provisions of section 9(2)(b)&(c) of the arbitration Act, (iv) if the arbitral tribunal is not formed by appointing an arbitrator, whether the petitioner-company is going to be non-suited or remains remediless and (v) whether collecting Bank is under any obligation to recover money from the drawee (importer).

-

At first, I would deal with the foremost issue, namely, whether this Court is competent to examine the issue as to whether there is existence of any arbitration agreement between the parties. In order to examine this issue, it would be profitable to be familiar with the provisions of section 12 of the arbitration Act, which reads as follows:

“12. Appointment of arbitrators:

(1) Subject to the provisions of this Act, the parties are free to agree on a procedure for appointing the arbitrator or arbitrators.

(2) A person of any nationality may be an arbitrator, unless otherwise agreed by the parties.

(3) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (1)

(a) in an arbitration with a sole arbitrator, if the Banks fail to agree on the arbitration within thirty days from receipt of a request by one party from the other party to so agree the appointment shall be made upon request of a party–

(i) by the District Judge in case of arbitration other than international commercial arbitration, and

(ii) in case of international commercial arbitration with three arbitrators, each party shall appoint one arbitrator, and the two appointed arbitrators shall appoint the third arbitrator who shall be Chairman of the arbitral tribunal.

(underlined by me)

-

If anyone skims through the provisions of section 12 of the arbitration Act, a primary understanding s/he would have is that section 12 of the arbitration Act does not in express terms gives an authority to a Court to examine the existence of an arbitration agreement. However, upon a minute reading of the same, it appears to me that certain words and expressions employed in it manifestly mean that the Court must examine, at least the prima facie existence of an arbitration agreement. The words incorporated in section 12(1)

(procedure for appointing arbitrator); words in section 12(3)(a)

(procedure for appointing arbitrator); words in section 12(3)(a)  (in an arbitration with a sole arbitrator); words in section 12(3)(a)(i)

(in an arbitration with a sole arbitrator); words in section 12(3)(a)(i)  (in case of arbitration other than international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(3)(a)(ii)

(in case of arbitration other than international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(3)(a)(ii)  (in case of international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(4)(c)

(in case of international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(4)(c)  (in case of arbitration other than international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(4)(d)

(in case of arbitration other than international commercial arbitration); words in section 12(4)(d)  (in case of international commercial arbitration) etc. are dearly indicative that the Court shall prima facie examine the existence of an arbitration clause. Further, throughout the entire provisions of section 12 of the arbitration Act, the words ‘party’ & ‘parties’ have been employed on a number of occasions and the meaning of the word “party” is given in section 2(g) of the arbitration Act, which reads as follows: “Party means a party to an arbitration agreement;”.

(in case of international commercial arbitration) etc. are dearly indicative that the Court shall prima facie examine the existence of an arbitration clause. Further, throughout the entire provisions of section 12 of the arbitration Act, the words ‘party’ & ‘parties’ have been employed on a number of occasions and the meaning of the word “party” is given in section 2(g) of the arbitration Act, which reads as follows: “Party means a party to an arbitration agreement;”. -

If the terminologies “party” and “parties” imprinted in section 12 of the arbitration Act are read with the above definition of “Party”, it becomes clear that section 12 of the arbitration Act will apply and an application thereunder can be maintained only if a party to an “arbitration agreement” invokes section 12 of the arbitration Act. What is an “arbitration agreement”–can be found in section 2(n) of the arbitration Act, which reads as follows:

“Arbitration agreement” means an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitration all or certain disputes which have arisen or which may arise between them in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not.”

- Since the learned Advocate for the respondent No. 2, Dr Sharif Bhuiyan, has placed before me the provision of section 11 of the Indian arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“the Indian Act, 1996”), in making his submission that section 12 of the arbitration Act more or less corresponds to section 11 of the Indian Act, 1996 and sub-section 6A of section 11 of the Indian Act, 1996 mandatorily requires the Court to examine the existence of an arbitration agreement, I would prefer to look at the provisions of section 11 of the said Indian Act, 1996, which is reproduced below:

S. 11. Appointment of arbitrators.–(1) A person of any nationality may be an arbitrator, unless otherwise agreed by the parties.

(2) Subject to sub-section (6), the parties are free to agree on a procedure for appointing the arbitrator or arbitrators.

(3) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (2), in an arbitration with three arbitrators, each party shall appoint one arbitrator, and the two appointed arbitrators shall appoint the third arbitrator who shall act as the presiding arbitrator.

(4) If the appointment procedure in subsection (3) applies and–

(a) a party fails to appoint an arbitrator within thirty days from the receipt of a request to do so from the other party; or

(b) the two appointed arbitrators fail to agree on the third arbitrator within thirty days from the date of their appointment, the appointment shall be made, upon request of a party, by the Supreme Court or, as the case may be, the High Court or any person or institution designated by such Court.

(5) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (2), in an arbitration with a sole arbitrator, if the parties fail to agree on the arbitrator within thirty days receipt from receipt of a request by one party from the other party to so agree the appointment shall be made, upon request of a party, by the Supreme Court or, as the case may be, the High Court or any person or institution designated by such Court.

(6) Where, under an appointment procedure agreed upon by the parties,–

(a) a party fails to act as required under that procedure; or

(b) the parties, or the two appointed arbitrators, fail to reach an agreement expected of them under that procedure; or

(c) a person, including an institution, fails to perform any function entrusted to him or it under that procedure, a party may request the Supreme Court or, as the case may be, the High Court or any person or institution designated by such Court to take the necessary measure, unless the agreement on the appointment procedure provides other means for securing the appointment.

(6A) The Supreme Court or, as the case may be, the High Court, while considering any application under sub-section (4) or subsection (5) or sub-section (6), shall, notwithstanding any judgment, decree or order of any Court, confine to the examination of the existence of an arbitration agreement.

-

From a plain reading of the above law of the Indian Act, 1996, my understanding is that there is no provision of “mandatorily” examining the issue of “existence of an arbitration agreement”; rather, a “mandatory prohibition” on the Court has been imposed by section 11(6A) of the Indian Act, 1996 that the Court shall not examine any issue other than the issue of “the existence of an arbitration agreement”. Although, this type of explicit provision has not been incorporated in section 12 of our arbitration Act, however, our Courts have laid down the above principle in many judgments. The High Court Division, in the case of Genesis Systems Limited vs. Clapp Mayne Inc. reported in 9 BLC 636, held at paragraph 10 that in an application for appointment of arbitrator, it would not be proper for the Court to enter into the merits of the case and the only point that calls for determination under section 12 of the said Act, 2001 is to see whether there is an agreement of arbitration between the parties and if there have been disputes between the parties arising out of the said agreement and, of course, keeping in mind that an arbitration agreement may not necessarily be in writing attached to the agreement, but may be a situation covered under section 9 of the arbitration Act.

-

Dr. Bhuiyan has also placed before me the provision of section 16 of the arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 of India, which is reproduced below:

Section 16. (Indian arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996) Competence of arbitral tribunal to rule on its jurisdiction:

(1) The arbitral tribunal may rule on its own jurisdiction, including ruling on any objections with respect to the existence or validity of the arbitration agreement, and for that purpose,–

(a) an arbitration clause which forms part of a contract shall be treated as an agreement independent of the other terms of the contract; and

(b) a decision by the arbitral tribunal that the contract is null and void shall not entail ipso jure the invalidity of the arbitration clause.

(2) A plea that the arbitral tribunal does not have jurisdiction shall be raised not later than the submission of the statement of defense; however, a party shall not be precluded from raising such a plea merely because he has appointed, or participated in the appointment of, an arbitrator.

(3) A plea that the arbitral tribunal is exceeding the scope of its authority shall be raised as soon as the matter alleged to be beyond the scope of its authority is raised during the arbitral proceedings.

(4) The arbitral tribunal may, in either of the cases referred to in sub-section (2) or subsection (3), admit a later plea if it considers the delay justified.

(5) The arbitral tribunal shall decide on a plea referred to in sub-section (2) or subsection (3) and, where the arbitral tribunal takes a decision rejecting the plea, continue with the arbitral proceedings and make an arbitral award.

(6) A party aggrieved by such an arbitral award may make an application for setting aside such an arbitral award in accordance with section 34.

-

In a bid to show similarity between section 16(a) of the Indian Act, 1996 and section 17(a) of our arbitration Act, Dr. Sharif Bhuiyan compared the provisions of section 17(a) of our arbitration Act with the provisions of section 16(a), respectively, of the Indian Act, 1996.

-

For the purpose of dealing with Dr. Bhuiyan’s submissions, it would be profitable to look at the provisions of section 17(a) of our arbitration Act, which runs as follows:

Section 17. (Arbitration Act, 2001) Competence of arbitral tribunal to rule on its own jurisdiction:

Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral tribunal may rule on its own jurisdiction on any questions including the following issues, namely–

(a) whether there is existence of a valid arbitration agreement;

(b) whether the arbitral tribunal is properly constituted;

(c) whether the arbitration agreement is against public policy;

(d) whether the arbitration agreement is incapable of being performed, and;

(e) what matters have been submitted to arbitration in accordance with the arbitration agreement.

-

Upon tallying the provisions of our arbitration Act as to “competence of arbitral tribunal to rule on its own jurisdiction” with that of the Indian provisions, as engraved in the marginal note of the respective provisions, I find that there is difference between our laws and Indian laws as to the competency of the arbitral tribunal to rule on its own jurisdiction, for, in our law the arbitral tribunal has been given the power to examine the issue as to “whether there is existence of a valid arbitration agreement”, but in the Indian law the arbitral tribunal is competent to examine both the aspects of the arbitration agreement i.e. (a) the existence of the agreement and (b) the validity of the said agreement. The Indian Supreme Court only recently took the view that the issue as to “existence of the arbitration agreement” can be examined by the Court. Previously, they were of the view that the function of the Court regarding appointment of an arbitrator is an administrative function not a judicial function and, as such, the arbitral tribunal should adjudicate upon the issue as to whether there is existence of any arbitration agreement,

-

From a minute examination of the language of section 17(a) and section 12 of the arbitration Act, I find that the provisions of these two sections are interrelated. Section 17 of the arbitration Act envisages

(existence of a valid arbitration agreement); it does not merely enumerate

(existence of a valid arbitration agreement); it does not merely enumerate  (existence of arbitration agreement). There is a significant difference between ‘an arbitration clause’ and ‘a valid arbitration clause’. Following are the few instances to demonstrate when a clause may constitute ‘an arbitration agreement’, but not a ‘valid arbitration agreement’; (1) if there had been an arbitration clause but the parties by mutual consent relinquish, (2) if the parties agree on incorporating arbitration clause with specific term that the same will expire unless invoked within certain period and the parties do not invoke the clause within time, (3) if both the parties annul the agreement including arbitration clause, (4) if one of the parties forges arbitration agreement and the tribunal may determine the arbitration agreement, (5) if the parties incorporate arbitration agreement which is void or otherwise barred under section 23 of the Contract Act, (6) if the agreement itself is barred by law or otherwise immoral, the arbitration clause as such will not be a valid agreement since the valid arbitration agreement is a sine qua non of a valid substantive agreement, (7) there is arbitration clause but the dispute referred to is not wide enough to cover the arbitration clause, therefore, for a particular dispute, there may not be a valid arbitration agreement to cover the dispute, (8) there is arbitration agreement but both the parties went to Court and resolved the dispute through Court of law and the arbitration clause becomes redundant and ineffective, (9) there is arbitration clause to be resolved through by a named arbitrator only and he dies and thereby the arbitration clause comes to an end; and (10) there is arbitration agreement but one of the parties had incapacity to enter into a valid arbitration agreement, making the arbitration agreement non-est.

(existence of arbitration agreement). There is a significant difference between ‘an arbitration clause’ and ‘a valid arbitration clause’. Following are the few instances to demonstrate when a clause may constitute ‘an arbitration agreement’, but not a ‘valid arbitration agreement’; (1) if there had been an arbitration clause but the parties by mutual consent relinquish, (2) if the parties agree on incorporating arbitration clause with specific term that the same will expire unless invoked within certain period and the parties do not invoke the clause within time, (3) if both the parties annul the agreement including arbitration clause, (4) if one of the parties forges arbitration agreement and the tribunal may determine the arbitration agreement, (5) if the parties incorporate arbitration agreement which is void or otherwise barred under section 23 of the Contract Act, (6) if the agreement itself is barred by law or otherwise immoral, the arbitration clause as such will not be a valid agreement since the valid arbitration agreement is a sine qua non of a valid substantive agreement, (7) there is arbitration clause but the dispute referred to is not wide enough to cover the arbitration clause, therefore, for a particular dispute, there may not be a valid arbitration agreement to cover the dispute, (8) there is arbitration agreement but both the parties went to Court and resolved the dispute through Court of law and the arbitration clause becomes redundant and ineffective, (9) there is arbitration clause to be resolved through by a named arbitrator only and he dies and thereby the arbitration clause comes to an end; and (10) there is arbitration agreement but one of the parties had incapacity to enter into a valid arbitration agreement, making the arbitration agreement non-est. -

Thus, from the aforesaid examples, it is apparent that the terms “arbitration agreement' and ‘valid arbitration agreement’ are different expressions and terminologies. Under section 12 of the arbitration Act, the Court will not venture to determine a valid arbitration agreement, but will satisfy itself that there is prima facie an arbitration agreement to assume jurisdiction for appointing arbitrator under section 12 of the arbitration Act. In other words, while the Court is competent to carry out the necessary scrutiny as to ‘existence of an arbitration agreement’

, in an appropriate application under section 17(a) of the arbitration Act, the arbitral tribunal will determine the “existence of a valid arbitration agreement”

, in an appropriate application under section 17(a) of the arbitration Act, the arbitral tribunal will determine the “existence of a valid arbitration agreement”  .

. -

In order for the Court to consider an application under section 12 of the arbitration Act, the fundamental requirement is that the petitioner must establish prima facie that an arbitration agreement as envisaged in section 9 of the arbitration Act exists. If the Court does not prima facie examine the existence of an arbitration agreement and appoints arbitrators) in all the applications filed before their Lordship, then a situation will arise which will be against public policy, which the Legislature never intended. I am of the view that the Legislature has not contemplated that the Court would act mechanically by merely referring the parties to an arbitration, whenever any party would approach the Court.

-

To sum up the discussions on this issue, all that I would say is that ordinarily the Court would not examine the existence of a valid arbitration agreement, because whether there exists any valid arbitration agreement or not, the same has to be determined by the arbitral tribunal. But when the Court will exercise its power under section 12 of the arbitration Act, it must necessarily satisfy itself as to the prima facie existence of an arbitration agreement. Therefore, if the Court, while assuming the jurisdiction of the prima facie existence of an arbitration clause for the purpose of appointing an arbitrator, the same will not be in conflict with section 17(a) of the arbitration Act. Section 17 of our arbitration Act is to be interpreted in the manner that the arbitral tribunal has the competence to rule on its own jurisdiction when such issues arise before it. This can happen when the parties have gone to the arbitral tribunal without recourse to section 12 of the arbitration Act. In other words, it would be incumbent upon the arbitral tribunal to determine the issue when the parties themselves constitute the tribunal without the Court’s intervention. Thus, this Court has jurisdiction regarding determination of existence of an arbitration agreement, when any application is filed before the Court under section 12 of the arbitration Act.

-

The findings on the first issue that this Court is competent to examine the existence of arbitration agreement leads me to take up the next issue, namely, whether there is any contractual relationship between the petitioner-company and the collecting Bank (Wells Fargo Bank), for examination. It transpires that Wells Fargo Bank (the respondent No. 2) acted for its customer, Milestone Clothing Resources LLC (respondent No. 1), as a Bank for facilitating a “Documentary Collection” transaction with the petitioner, Corona Fashion Limited. The “Documentary Collection” transaction was handled pursuant to the Uniform Rules for Collection, International Chamber of Commerce Publication No. 522 (commonly known as URC-522). At this juncture, it is imperative for this Court to know about the “Documentary Collection” transaction.

-

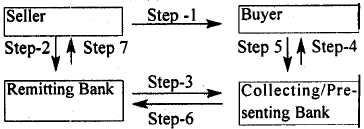

A ‘Documentary Collection’ is a trade transaction in which the exporter hands over the task of collecting payment for goods supplied to his Bank, which sends the shipping documents to the importer’s Bank together with the payment instructions. ‘Documentary Collection’ is the process in which the seller entrusts his Bank to present documents in relation to a trade deal to the buyer’s Bank to present or release documents to the buyer against certain conditions. Documentary Collection is subject to the Uniform Rules of Collection modelled by International Chamber of Commerce, Publication No. 522, which has been named ‘URC-522’. There are two types of Documentary Collection. (1) Documents against Payment (‘D/P’), in which the Bank will release documents to the buyer upon his payment and (2) Documents against Acceptance (‘D/A’), by which the Bank will release documents to the buyer upon his acceptance of a Bill of Exchange that undertakes to pay at a determinable future date. The instant case is a case of Documents against Acceptance (D/A). In a ‘Documentary Collection’ transaction a number of parties are involved. They are (a) Seller/Exporter: The seller/exporter is also known as the Drawer in a ‘Documentary Collection’. The seller/exporter will ship the goods to the buyer based on the sale contract and submit documents to his banker with instructions for collecting payment; (b) Remitting Bank: The remitting Bank is the seller/ exporter’s Bank. It will send the documents to the buyer’s Bank with instruction for collecting payment. Upon receipt of payment from the buyer’s Bank, the remitting Bank will credit the net proceeds to the seller/ exporter’s account; (c) Collecting/Presenting Bank: The collecting/presenting Bank is the agent of the remitting Bank in the buyer’s country. Its main function is to forward the documents and collection instruments to the buyer. The presenting Bank is the Bank that presents the documents to the buyer for payment or acceptance based on the collection instructions. Upon receipt of the payment from the buyer, the presenting Bank will pay the net proceeds to the collecting Bank, which will in turn pay the remitting Bank after deducting its own charges. A collecting Bank may also become the presenting Bank in the buyer’s country; (d) Buyer/ Importer: The buyer/ importer is also known as the drawee in the “Documentary Collection”. The buyer will pay the dues or accept the bill of exchange. In return, the buyer/ importer will obtain the documents to allow him to clear the goods.

-

A flow of ‘Documentary Collection’ is shown in the following diagram.

Step-1: Seller ships the goods to the buyer’s country as per the sales contract. Step-2: Seller presents documents to the remitting Bank with clear instruction for collection of payment. Step-3; Remitting Bank forwards the documents and collection instruction to the collecting/presenting Bank. Step-4: Collecting/presenting Bank presents documents to the buyer for payment. Step-5: Buyer pays for the document. Step-6: Collecting/presenting Bank remits the net proceeds to the remitting Bank after deducting its own charges. Step-7: Remitting Bank credits the net proceeds into the seller’s account after deducting its own charges.

-

The respondent No. 2 acted in the transaction as the collecting Bank and the presenting Bank, having acted under the collection instructions of the remitting Bank, i.e. Brac Bank Limited (respondent No. 4). Under the aforesaid instructions, respondent No. 4 authorized the respondent No. 2 to handle documents on a collection basis and to release documents to the respondent No. 1 (Milestone Clothing Resources LLC) upon receipt of respondent No. 1 ’s letter of undertaking to pay the collection in 90 days. Respondent No. 2 duly carried out its obligations in such capacity and released the documents to respondent No. 1 after receiving their signed letter of undertaking.

-

Thus, the contractual relationship under URC-522 existed between respondent No. 2 and respondent No. 4 (remitting bank), to which the petitioner-company had no privy. In a “Documentary Collection” under URC-522, it is now established that URC-522 does not create privity of contract between the principal/seller and the collecting Bank. As the collecting Bank is the agent of the remitting Bank, there is no privity of contract between him and the customer, i.e. the seller. This is based on the principle that there is normally no privity of contract between a principal and his sub-agent. Even if the remitting Bank engages a collecting Bank, which is specifically nominated by the customer and who is not one of the remitting Bank’s usual correspondences, there is no privity of contract between the collecting Bank and the customer. The High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, Commercial Court, in the case of Grosvenor Casinos Limited vs. National Bank of Abu Dhabi, reported in 2 All ER (Comm) 112, held that URC-522 does not create privity of contract between the principal and the collecting Bank. To conclude the issue in a simpler version, all that I record here is that there being no ‘offer’ by the petitioner-company to Wells Fargo Bank, resultantly, there is no ‘acceptance’ from Wells Fargo Bank and, thus, there is no consideration and, therefore, it is crystal clear that there is no existence of any contract between the petitioner-company and the respondent No. 2.

-

I would, now, take up the third issue, namely, whether the legal notice sent by the petitioner’s lawyer to the collecting Bank and the reply thereto by the collecting Bank compose an implied form of arbitration agreement under the provisions of section 9(2)(b) & (c) of the arbitration Act.

-

It would be useful, if we look at the provisions of section 9 of the arbitration Act, which run as follows:

- Form of arbitration agreement–(1) An arbitration agreement may be in the form of an arbitration clause in a contract or in the form of a separate agreement.

(2) An arbitration agreement shall be in writing and an arbitration agreement shall be deemed to be in writing if it is contained in–

(a) a document signed by the parties;

(b) an exchange of letters, telex, telegrams, fax, e-mail or other means of telecommunication which provide a record of the agreement; or

(c) an exchange of statement of claim and defence in which the existence of the agreement is alleged by one party and not denied by the other.

Explanation–The reference in a contract is a document containing an arbitration clause constitutes an arbitration agreement if the contract is in writing and the reference is such as to make that arbitration clause part of the contract.

-

From the marginal note (Head note) of section 9 of the arbitration Act, it is vividly clear that the provisions of this section are about the form of arbitration agreement. Section 9(2) of the arbitration Act provides, among others, that an arbitration agreement must be in writing and the agreement may be deemed to be in writing if it is contained in a contract signed by the parties or contained in written communication as elaborated in clauses (a) to (c) under section 9(2) of the arbitration Act. It further appears that section 9(2)(b) of the arbitration Act is not an alternative to section 9(1) of the arbitration Act, but an explanation to determine whether an arbitration agreement is in writing or not. As per section 9(1) of the arbitration Act, an arbitration agreement can be in the form of a clause in a contract or as a separate agreement. Section 9(2) of the arbitration Act went further to explain that such agreement as mentioned in section 9(1) of the arbitration Act should be in writing, in other words, oral agreement is not acceptable. In addition, section 9(2) of the arbitration Act also enlightens that an arbitration agreement will be considered as written if any of the conditions, laid down under it, is satisfied.

-

For determining the existence of an arbitration agreement through section 9(2)(b) of the arbitration Act, the following conditions are to be satisfied: (1) the subject matter of agreement i.e. arbitration agreement shall be mentioned in a letter, telex, telegram, email, fax or any other medium and (2) the party on whom such agreement has been served shall agree to such communication. If the second condition as aforesaid is disregarded, and section 9(2) of the arbitration Act is found independent, then it would make arbitration obligatory only on the willingness of one party.

-

For determining the existence of an arbitration agreement through section 9(2)(c), the following conditions are to be satisfied: (1) the subject matter of agreement i.e. arbitration agreement shall be mentioned in an exchange of statement of claim or defence and (2) the agreement is alleged by one party, and not denied by the other. It appears from the second condition that the affirmation to enter into an arbitration agreement is confirmed, by the party to whom such statement of claim of defence has been served, through omission to decline such proposal.

-

In other words, under section 9(2) of the arbitration Act, an arbitration agreement must be in writing though no special form is prescribed for that. Such an agreement can be in one document or can be gathered from several documents also. It can be gathered from correspondences consisting of letters, fax messages, telegrams or even telex messages. An arbitration agreement can also be constituted when the existence of the agreement is depicted in a statement of claim and defence and the existence of the contract is alleged by one party and not denied by the other. The arbitration clause may exist either in the circumstances by way of incorporating an arbitration agreement or in the situation as contemplated in section 9 of the arbitration Act. An arbitration agreement may be included by way of implied terms. For example, the agreement in World Cotton Association by way of implied term may incorporate an arbitration clause. Similarly, in documentary collection, if the parties by express term decide to include ICC arbitration Rules in their contract, then the parties shall be bound by such term. In the instant case, from the documents on record, it appears that there is no implied term for any arbitration.

-

From the above discussions, it leads me to hold that in order to constitute an arbitration agreement, a written document must be present, which states or refers or demonstrates the ad idem intention of the parties to adopt a quasi judicial method, i.e., a private tribunal as to dispute resolution, whose decision shall be binding upon both the parties.

-

In Thomson Press India Limited vs. NCT of Delhi, reported in 1999 (1) Arb LR 421, the Court decided that even though, an arbitration agreement does not necessarily have to include words like ‘arbitrator’ or ‘arbitration’, the words used for the purpose must be words of choice and determination to go to arbitration.

-

In Jagdish Chander vs. Ramesh Chander MANU/SC/7338/2007 : (2007) 5 SCC 719, the Court decided that the essential elements of an arbitration agreement are, (i) the agreement should be in writing; (ii) the parties should have agreed to refer any dispute between them to the decision of a private tribunal; (iii) the private tribunal should be empowered to adjudicate upon the disputes in an impartial manner and (iv) the parties should have agreed that the decision of the private tribunal in respect of the disputes shall be binding upon them. Ujwala Raje Shah vs. Veer Corp. 2014 (2) RAJ 598, connotes “Arbitration Agreement” as, “If the terms of the agreement indicate intention on the part of all the parties to refer the dispute to the arbitral tribunal for adjudication and their willingness to be bound by the decision of such tribunal, such agreement would amount to arbitration agreement.”

-

If I now turn back to the facts of the present case with a view to see the applicability of the above principles of law, it would appear that since Wells Fargo Bank expressly declined their intention to settle the dispute through arbitration, the existence of an arbitration agreement can be found neither under section 9(2)(b) of the arbitration Act, due to the lack of their consent to enter into such agreement, nor under section 9(2)(c) of the arbitration Act, due to their express denial. In other words, from the communications dated 5-10-2017 and 14-11-2017 between the petitioner and the respondent No. 2, there seems to have no indication or reference to any expression of either party to a pre-meditated consensus to refer any potential dispute to an arbitrator for dispute resolution and hence, while considering whether there exists an arbitration agreement between the parties under reference, the communications dated 14-11-2017 and 5-10-2017 do not attract section 9(2)(b) & (c) of the arbitration Act. By merely raising a dispute, an arbitration does not come into play as a matter of course. Thus, I find that the petitioner’s legal notice dated 5-10-2017 to the respondent No. 2, and the reply dated 14-11-2017 to the legal notice do not attract section 9(2)(b) and (c) of arbitration Act. Section 9(2)(b) and (c) of arbitration Act would have applied only if the aforesaid legal notice by the petitioner and the reply by the respondent No. 2 contained an agreement, i.e. meeting of the minds, to refer disputes between these parties to arbitration. The reply dated 14-11-2017 issued by the respondent No. 2 does not contain indication whatsoever that the respondent No. 2 was willing to refer the dispute to arbitration. To the contrary, the respondent No. 2 clearly stated that if the petitioner was to pursue any legal action against the respondent No. 2, the only proper forum would be USA Courts. Thus, there was no arbitration agreement between the petitioner-company and Wells Fargo Bank, even through written correspondence. By no stretch of imagination, thus, it can be said that there exists any arbitration agreement between the petitioner-company and Wells Fargo Bank under sections 9(2) &(3) of the arbitration Act. However, since Coreattire Fashion (respondent No. 6) through its reply letter dated 4-2-2018 (Annexure H) made the statement “My client proposes to appoint one arbitrator for my aforesaid client himself (at paragraph 6), this scenario satisfies all the conditions under section 9(2)(b) of the arbitration Act, for, the above-quoted statement amounts to a consent to settle the dispute through arbitration.

-

Now, let me deal with the issue No. 4, namely, if the arbitral tribunal is not formed by appointing an arbitrator, whether the petitioner-company is going to be non-suited or remains remediless.

-

There is no scope under the arbitration Act to refer a dispute to arbitration only on the ground of financial hardship or any other inconvenience of a party, as has been pleaded in this case that since the petitioner is a Bangladeshi party and the counterparty to the dispute is a resident in USA, it would not be feasible to contest the suit in the USA Court given the value of the subject-matter of arbitration is trivial. The basis for appointing an arbitrator is the existence of an arbitration agreement, and not the supposed inconvenience of a particular party. If it is possible to appoint an arbitrator without the existence of an arbitration agreement, any and all parties can apply to the Court for appointment of arbitrators by pleading inconvenience in pursuing the relevant remedy under the applicable law. This would make arbitration agreements, which are foundations of all arbitrations and the law of arbitration, entirely redundant. If this Court takes a view that a party may maintain an application under section 12 of the arbitration Act even in the absence of a prima facie arbitration agreement on the ground of inconvenience, the whole scheme of the arbitration Act would become frustrated and a floodgate would open allowing a party to any civil dispute to apply to Court for constitution of an arbitral tribunal. In my opinion, such a result would be opposed to public policy.

-

There is no bar to a suit against the importer and the collecting Bank in Bangladesh if a case of fraud or otherwise can be established. The plaint in such event has to disclose a valid cause of action to maintain the suit in Bangladesh. If the Bangladeshi party can establish that the cause of action arose wholly or in part in Bangladesh, a Court in Bangladesh may also exercise jurisdiction over such dispute (section 20 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908). The difficulty lying here may be that there is no reciprocity of enforcement of judgment between USA and Bangladesh. Therefore, even if a verdict is obtained in Bangladesh, the same cannot be enforced in USA. However, the verdict of Bangladeshi civil Court may be enforced, in a roundabout manner, with the assistance of Bangladesh Bank and other scheduled Banks. For example, if the petitioner-company somehow comes to know that the importer or the Wells Fargo Bank has any money in any Bank in Bangladesh or has stored any goods anywhere in Bangladesh, it may seek to attach the same by the order of the Court. My considered view, thus, is that since the petitioner-company is free to sue the respondent No. 2 (Wells Fargo Bank) and respondent No. 1 (importer) either in the competent Court of USA or in Bangladeshi civil Court and, further, since the petitioner-company can commence arbitration in Bangladesh any time with the importer (respondent No. 1), the petitioner-company is not going to be either non-suited or remain remediless.

-

The last issue to be dealt with by this Court is whether the collecting Bank is under any obligation to recover money from the drawee (importer). In case of a transaction through letter of credit (“L/C”), an issuing Bank (the buyer’s or importer’s Bank) unconditionally guarantees to pay the seller’s Bank when the shipping documents, as listed in the L/C, are presented in an acceptable condition. However, in a ‘Documentary Collection’ arrangement (“D/A”), as per Article 16 of the URC-522, the collecting Bank is responsible to make payment only if it has collected payment from the buyer. It has no independent obligation to make payment, if the buyer has not made payment of the agreed amount to the collecting Bank. URC-522 clearly sets out the respective obligations of the parties, and does not contain any provision requiring the collecting Bank to make any payment if it has not received the amount concerned from the buyer. Thus, the difference between an L/C transaction and D/A transaction is that in the former case the buyer’s Bank guarantees to the L/C beneficiary Bank (i.e. exporter’s Bank) that it would make payment on receipt of compliant shipping documents, whereas in the latter case the buyer’s Bank does not provide any such independent guarantee/undertaking.

-

In this case, the collecting Bank had engaged in a ‘Documentary Collection’ with an obligation to send the money to the remitting Bank, only when the importer will make payment under D/A. Under the provisions of ‘URC-522’, the collecting Bank is under no obligation to take any collateral security towards securing the deferred payment (D/A) at the time of releasing the documents to the drawee, unless the collecting Bank is otherwise instructed by the drawer. URC-522 does not impose any obligation upon the collecting Bank to obtain collaterals from the drawee; it merely obliges the collecting Bank to comply with the collection instructions provided by the drawer. In order to protect its interest, the collecting Bank, sometimes, becomes tempted to release the documents under a trust receipt. Under such a document a genuine trust is constituted, the drawee being the trustee, the collecting Bank being the beneficiary and the proceeds of sale of the goods collected by the drawee being the trust property. In other words, the collecting Bank may enter into any arrangement with the drawee for securing the collecting Bank’s interest; so long such arrangements do not contravene the collection instructions by the drawer or the remitting Bank.

-

In this case, the collecting Bank had received instructions from the remitting Bank merely to pass the documents onto the importer upon taking an undertaking from the importer that the latter shall pay within 90 days and, accordingly, the collecting Bank has performed its duties. Whether the collecting Bank has acted in good faith and has exercised reasonable care in dealing with the petitioner-company’s ‘Documentary Collection’, as per the provisions of Article 9 of the URC-522, or it has violated any provisions of Unified Commercial Code (UCC), which has been termed by the learned Advocate for the petitioner-company to be a law of the USA, is a question of fact to be examined by the Court, in absence of any arbitral tribunal which could not be constituted due to non-incorporation of an arbitration clause in the correspondences of “Documentary Collection”. Now-a-days, many of the remitting Banks inscribe the provisions of arbitration in the L/C and Documentary Collection. It has become a frequent custom to incorporate the provision of arbitration in dealing with Documentary Collection, more particularly in dealing with transactions relating to Documents by Acceptance (D/A). Since the practice of “Documentary Collection” is highly specialized and often counter-intuitive to the general commercial lawyer, the judicial process has not generally afforded speedy, final and sound relief desired by the parties to a dispute under Documentary Collection. To resolve this predicament, International Centre for Letter of Credit arbitration INC was founded in 1996, which is located in Washington DC, USA. This Centre has established a set of rules, namely, ICLOCA Rules of arbitration. These rules are modelled to assist in the resolution of disputes arising out of international banking operations, including Letters of Credit, Confirmations or Advices, Documentary Collections, Funds Transfers etc. The interested parties of the transactions may refer the dispute under ICLOCA Rules by inserting a clause into the undertaking or agreement providing that all future disputes, arising out, or in connection to the agreement be subjected to the Centre for Resolution under those Rules. There are two circumstances in which a dispute might be referred to arbitration under ICLOCA Rules and administered by the centre: (i) a clause may be inserted into the undertaking or agreement providing that all future dispute arising out of, in connection with or relating to, that undertaking or agreement be submitted to the centre for resolution under these rules, (ii) an existing dispute may also be referred to the centre for resolution by agreement of the parties, even if there was no advance agreement to arbitration.

-

There are different models of law governing the contractual relationship between the parties. Once the parties adopt any such model in their contractual relationship, the arbitration clause incorporated in such model impliedly becomes applicable in their contractual transactions. For example, if the parties adopt ICC Rules of arbitration or Rules of the International Cotton Association Limited, the arbitration clauses incorporated therein become impliedly applicable and binding in their contract. Therefore, in “Documentary Collection”, if the parties by express term decide to include ICC arbitration Rules or ICLOCA Rules of arbitration in their contract, then the parties shall be bound by such term,

-

The parties to a transaction have the flexibility to agree to the dispute resolution mechanism to be applied to a transaction. Such agreement varies from one transaction to another, depending on various commercial and legal considerations. There is no uniform practice of any specific dispute resolution mechanism. The URC-522 does not contain any provision to the effect that the parties to a D/A transaction shall refer their dispute to arbitration.

-

Since there is no privity between the principal and the collecting Bank, in England, the customer/principal may invoke the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act, 1999 to sue the collecting Bank. Since no such Act is prevalent in Bangladesh, the principal cannot sue the collecting Bank. In such circumstances, the proper remedy of the customer would be to request the remitting Bank, in return for an indemnity against the incurred expenses to claim against the collecting Bank.

-

In this case, admittedly the transaction of this case took place under the URC-522 and since the collecting Bank has no obligation to take any collateral security towards securing the deferred payment at the time of releasing the documents to the drawee (importer) under the URC-522, the collecting Bank is not bound to take any initiative to recover the collections (money) from the importer.

-

After carrying out the examination of all the five issues, as framed by me for the purpose of adjudication of this case, I find that this case (application under section 12 of the arbitration Act) is liable to fail against the respondent No. 2 (collecting Bank), mainly, on the grounds of nonexistence of the arbitration agreement, albeit the learned Advocate for the petitioner has put his best effort to make out a case on the strength of Preamble, section 2(c) and section 9(2)(b) of the arbitration Act, 2001. He has particularly emphasized on the Preamble of arbitration Act, 2001 in an expectation to pursue this Court that the scheme and object of repealing the old law of arbitration and enacting the new arbitration Act in 2001 is to facilitate arbitration for any ‘international commercial dispute’ to be held in Bangladesh. In order to address the above submissions, it would be pertinent to briefly know about the history of arbitration in our jurisdiction. In this part of the world (sub-continent), the concept of arbitration is known to the people from time immemorial. In good old days, disputes between private individuals used to be placed before ‘Panchas’ and ‘Panchayats’. Likewise, commercial matters were decided by ‘Mahajans’ and ‘Chambers’. Formal arbitration proceedings, however, had come into existence after the Britishers started commercial activities in India. The provisions relating to arbitration were found in the Code of Civil Procedure, 1859 (CPC) and, then, in subsequent CPCs. A full-fledged law pertaining to arbitration in India was the arbitration Act, 1899. A consolidated and amended law relating to arbitration was passed in 1940, known as the arbitration Act, 1940. Protracted, time-consuming, atrociously expensive and complex Court-procedures impelled the commercial world to an alternative, less formal, more effective and speedy mode of resolution of disputes by a Judge of choice of the parties which culminated into passing of an arbitration Act. Experience, however, belied expectations. Proceedings became highly technical and thoroughly complicated. The provisions of the Act made ‘lawyers laugh and litigants weep’. Representations were made from all quarters of the society to amend the law by making it more responsive to contemporary requirements. Moreover, apart from arbitration, conciliation has been getting momentum and worldwide recognition as an effective instrument of settlement of disputes. There was no composite statute dealing with all matters relating to arbitration and conciliation. The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) adopted a Model Law in 1985 on International Commercial arbitration. The General Assembly of the United Nations recommended its member-States to give due consideration to the Model Law to have uniformity in arbitration procedure which resulted in passing of the arbitration Act, 2001. The Act is almost a complete Code in itself and consolidates and amends the law relating to domestic arbitration, international commercial arbitration and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. The Preamble expressly refers to International Commercial arbitration.

-

Thus, with the passage of time, the customs and laws relating to arbitration of disputes have achieved the status of the finest law of our jurisdiction, as now it contains both procedural and substantive laws. It has clearly now categorized the provisions for local arbitration and the international arbitration. The latest position of the laws relating to arbitration of all the countries of the world is, which has now become an inviolable law, like Veda’s statement, that there cannot be any arbitration without any arbitration agreement. I find the submissions of the learned Advocate for the petitioner-company to be a desperate attempt to bring his case within the purview of arbitration agreement, although his agreements do not attract the Preamble, section 2(c) and section 9(2)(b) in any manner. Since, this Court finds that there is no existence of any arbitration agreement with the Well’s Fargo Bank, this application cannot succeed against it. However, the arbitration may be held with Coreattire Fashion Ltd (respondent No. 6) who had consented to the proposal of arbitration given by the petitioner-company.

-

Before parting with the judgment, I find it pertinent to make an observation that the legislature may consider incorporation of a provision at an appropriate place in the arbitration Act that the Court (the District Judge Court and the High Court Division) shall examine the issue of existence of an arbitration agreement without entering into the merit of the case, when an application for any interim order or for appointment of an arbitrator is made before the Court.

-

I must record here the invaluable assistance rendered by Mr. Ahsanul Karim who appeared before this Court as an amicus curiae. He took the pain of going through all the relevant laws of Bangladesh and the up-to-date Legal Instruments on International Trade and presented a very precious written submission, significant portions of which have been used by me in this judgment. Although, currently, Mr. Ahsanul Karim is an Advocate of this Court with a single star, however, it is hoped that very soon he will be honoured with double stars by the Honourable Appellate Division, for, in my estimation, he possesses all the qualifications, knowledge, experience and professional etiquette to be endowed with the professional status of a ‘Senior Advocate’. Also, the performances of the learned Advocate for the petitioner Mr. Syed Mohidul Kabir and the learned Advocate for the respondent No. 2 Dr Sharif Bhuiyan were highly commendable in assisting this Court.

-

In the result, this application is rejected. However, there shall not be any order as to costs.

The Office is directed to send a copy of this judgment to the Legislative Division of the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs for their consideration as to incorporation of the proposed provision, as observed by this Court in the penultimate para of this judgment.