IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH (APPELLATE DIVISION)

Civil Appeal No. 268 of 2009

Decided On: 05.03.2014

Appellants: Tata Power Company Limited

Vs.

Respondent: Dynamic Construction

**Hon’ble Judges:**Nazmun Ara Sultana, Syed Mahmud Hossain, Muhammad Imman Ali and Mohammad Anwarul Haque, JJ.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Ahsanul Karim, Advocate, instructed by Md. Wahidullah, Advocate-on-Record

For Respondents/Defendant: A.Y. Mosheuzzaman, Advocate, instructed by Bivash Chandra Biswas, Advocate-on-Record

Subject: Contract

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

Relevant Section:

CONTRACT ACT, 1872 - Section 73

**Acts/Rules/Orders:**Constitution Of The People’s Republic Of Bangladesh - Article 8; Contract Act, 1872 - Section 73

Citing Reference:

Discussed

4

Mentioned

3

Case Note:

Since the appellant was not in breach of the contract and the contract was rightly terminated due to breach of the terms by the respondent, therefore, no question of liability will arise against the appellant.

We have considered the submissions of the learned advocates appearing for the parties concerned and perused the impugned judgement as well as other evidence and materials on record.[17]

The claim of the respondent in this case, which was contested before the learned Arbitrator appointed upon agreement of both the parties, is based on the LOI dated 10.09.2004 and a Work Order dated 28th October, 2004 which in turn reflected the arrangement between the parties, as contained in the Minutes of Meeting dated 5th August, 2004. In that meeting the appellant and the respondent discussed finalisation of a contract for the construction of a 230 KV Khulna-Bheramara-Ishurdi Transmission Line by the respondent as a sub-contractor. One of the terms agreed in that meeting was that the work order given to the respondent would be valid only if PGCB approved the respondent as a sub-contractor. This condition was again reflected in Column 10 of Article 8 of the Work Order dated 28 October. 2004. It may be mentioned at this stage that the respondent admitted that he did not take approval of the PGCB. On the other hand, the respondent based his claim for expenditure incurred in placing materials and equipment on the site in accordance with the Letter of Intent dated 10 September, 2004. [18]

We find that the Letter of Intent (Annexure-C) contains a request by the appellant to the respondent to accept the Letter of Intent and “arrange mobilisation of all resources based on this LOI”. We note from the LOI also that there is a condition that the respondent was to arrange approval from PGCB before commencement of foundation work, i.e. before 1st October, 2004. The claim of the respondent is that on the basis of the LOI and Work Order it was pressurised by the appellant into mobilisation of materials and equipment. [19]

Before the High Court Division as well as before this Division learned Counsel for the appellant made a submission to the effect that only the person in breach of contract is liable for the loss and damage caused by the breach of contract. He submitted that the learned Arbitrator wrongly applied the principle of the decision in Anglia Television Limited v. Reed. He pointed out that in the case under reference the defendant entered into the contract knowing that expenditure had already been incurred by the plaintiffs and, therefore the defendant must have contemplated, or it was reasonable to impute contemplation to him, that if he broke the contract the expenditure would be wasted. [34]

Let us consider Section 73 of the Contract Act which provides as follows:

“73. Compensation for loss or damage caused by breach of contract-when a contract has been broken the party it who suffers by such breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby which naturally arose in the usual course of things from such breach, or which the parties knew, when they made the contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it.

Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach. " [35]

Kamaluddin Hossain J. (as his Lordship was then) in Amin Jute Mills vs. M/s. A.R.A.E. 28 D.L.R. (AD) 76- referring to section 73 of the Contract Act observed as follows:

“An analysis of section shows that, when it is found that a party to a contract is in breach, he must pay compensation for the loss or damages caused by the breach to the other contracting party. That is the principal consideration.” [36]

Since in the facts of the instant case the finding of the learned Arbitrator was that it was the claimant who was in breach of the contract and not the defendant, clearly the claimant does not qualify to claim under section 73 of the Contract Act. In this regard we may refer to the decision in the case of Bangladesh Power Development Board and others vs. M/s. Arab Contractor (BD) Limited and others, where it was held that: “An analysis of section shows that, when it is found that a party to a contract is in breach, he must pay compensation for the loss or damages caused by the breach to the other contracting party. That is the principal consideration”. [41]

JUDGMENT

Muhammad Imman Ali, J.

-

This Civil Appeal, by leave, is directed against the judgment and order dated 05.06.2007 passed by a Single Bench of the High Court Division in arbitration Case No. 03 of 2006 modifying the Arbitral Award dated 29.08.2006 and directing the appellant to pay the respondent a sum of Taka 61,60,000/- only with interest accrued thereon from the date of Arbitral Award dated 29.08.2006 at the rate of 2%.

-

The facts of the case, in brief, are the appellant Tata Power Company Limited (Tata) is a company incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1913. The respondent M/S. Dynamic Construction (Dynamic) is a proprietorship concern engaged in the construction of civil and electrical works. The appellant was appointed as contractor by the Power Grid Company of Bangladesh Limited (PGCB) an enterprise of the Bangladesh Power Development Board, for the Design and Construction of 230 KV Khulna-Bheramara-Ishurdi Transmission Line on turnkey basis under a contract executed on 30.05.2004. The appellant thereafter invited tenders from qualified contractors of Bangladesh in respect of the said work for being appointed as sub-contractors. The respondent submitted its bid and its offer was accepted. The appellant and the respondent along with two other contractors whose tenders had also been accepted held several meetings and an agreement was signed between the parties. In the final meeting held on 05.8.2004 Minutes of the Meeting (MOM) was drawn up and signed by the appellant and the respondent. In accordance with the provisions of the MOM the respondent was to undertake the work for construction of 68 KM. 230 KV transmission line between Khulna Central and New Khulna Sub-station under certain terms and conditions. The appellant thereafter, vide letter dated 10.09.2004, issued a Letter of Intent (LOI), inter alia, with a request to mobilise all resources so as to commence the foundation work on 01.10.2004. Accordingly, the respondent began the work of mobilisation for commencement of the work. It may be noted here that the Letter of Intent (LOI) dated 10.09.2004 stipulated that the respondent should “arrange mobilization of all resources based on this LOI, so as to commence foundation work on 1st October, 2004.” However, other conditions were mentioned “which would form an integral part of our detailed Purchase Order”. The first of these conditions was that the respondent had “to arrange approval from PGCB before commencement of foundation work i.e. before 1st October, 2004.”

-

While the respondent was performing its obligations in accordance with the LOI, the appellant terminated the contract by a fax massage dated 01.01.2005 (transmitted on 08.1.2005). The respondent vide letter dated 02.03.2006 disputed the letter of termination and invoked the arbitration proceeding by issuing a notice of arbitration. The parties mutually agreed to appoint Justice Naimuddin Ahmed to act as the sole Arbitrator for resolving the disputes between them.

-

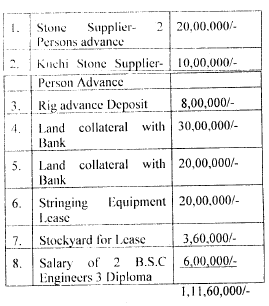

The respondent (Claimant) made its claim by submitting its statement of claim stating, inter alia, that, in part performance of the contract, it mobilised the materials and equipment as instructed but the appellant illegally terminated the contract on 01.01.2005. In the statement of claim, the respondent claimed that he had invested the following amounts towards execution of the contract:

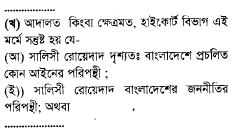

The Claimant prayed for the following relief:

(a) A declaration to the effect that the termination of the contract by the respondent No. 1 (appellant) by the fax message dated 01.01.2005 is illegal.

(b) Damage to the tune of Tk. 1,30,60,000/- incurred by it for mobilisation of resources and

(c) Costs.

-

The appellant denied the allegations made in the statement of claim by filing a statement of defence and also laid a counterclaim against the claimant in the form of damage for a sum of Tk. 8,25,000/-.

-

The Arbitral Tribunal after hearing the parties passed the Award on 29.08.2006. In deciding the Award the learned Arbitrator raised the following issues.

“1. Was the order of termination of the contract by Respondent No. 1 according to the terms of the contract and lawful?

Is the Claimant entitled to claim any amount from Respondent No. 1 for his alleged mobilisation of resources?

Did the Claimant incur any expenditure for mobilisation of resources as alleged? If so, to what extent?

Is the counter-claim laid by Respondent No. 1 sustainable? If so, to what extent?

Is the Claimant entitled to get any declaration to the effect that the termination of the contract with it by Respondent No. 1 is illegal and without lawful authority and a violation of the contract?

Is the Claimant entitled to get any amount for mobilisation of resources? If so to what extent?

Is the Respondent No. 1 entitled to get any amount as damage from the Claimant? If so to what extent?

To what other relief, if any, are the parties entitled?”

- Issue No. 1 was decided against the claimant. Issue Nos. 2 and 3 were decided partly in favour of the claimant. The Tribunal came to a finding that the claimant had incurred the following expenditure for mobilisation of resources.

- Issue No. 4 was decided against the respondent No. 1 and its counter-claim was dismissed. The Tribunal determined issues No. 5, 6, 7 and 8 and passed the award in the following terms.

AWARD

“1. The claim of the claimant is allowed in part. The claimant is awarded an amount of Taka 1,11,60,000/- only payable by the respondent No. 1.

-

The respondent No. 1 shall pay the aforesaid amount of Taka 1,11,60,000/- within one month from this date failing which interest at the rate of 2% per annum on the amount of the award, or if part payment is made, on the amount remaining unpaid shall be charged and payable by the respondent No. 1.

-

If the respondent No. 1 fails to comply with the order for payment within the time above, the amount of the award shall be realised according to law.

The claim of the claimant for declaration to the effect that the order of termination of the contract between it and the respondent No. 1, by the respondent No. 1 vide its order under Ref. TPCI/BD/PGCB(W7) KI/62 dated January 1st, 2005 is illegal and without lawful authority, is dismissed.

The counter-claim of the respondent No. 1 for damages to the tune of Taka 8,25,000.00/- to be payable by the claimant, is dismissed.

Considering the circumstance that success is divided and other circumstances, the claimant and the respondent No. 1 are directed to bear their respective costs of this arbitration proceeding.

The proceedings as against the respondents Nos. 2 and 3 stand dismissed.

-

Against the said award, the appellant Tata Power Company Limited filed arbitration Case No. 3 of 2006 before the High Court Division.

-

By the impugned judgment and order, the High Court Division set aside the award of damage for the sum of Tk. 50.00,000/- under the head “land Collateral with Bank” under serial numbers 4 and 5 and upheld the remaining part of the award passed by the learned Arbitrator subject to the aforesaid modification.

-

Against the said judgement and order dated 05.06.2007 the appellant filed Civil Petition for Leave to Appeal No. 114 of 2008.

-

Leave was granted to consider the following grounds:

I. Whether the High Court Division acted illegally in not considering that the learned Arbitrator passed the Award of Tk. 1.11,60,000.00 in favour of the respondent contrary to the provisions of section 73 of the Contract Act, 1872 because the respondent having admittedly committed breach of contract is not entitled to get any compensation and as such, the award is clearly opposed to section 73 of the Contract Act.

II. Whether the High Court Division acted illegally in not considering that the learned Arbitrator misconducted himself in contradicting his own finding, on the one hand holding that the respondent breached the very important term of the contract while on the other hand awarded an amount of Tk. 1,11,60,000.00 as compensation to the respondent who himself was in breach of the contract in complete violation of section 73 of the Contract Act; and

III. Whether the High Court Division acted illegally in not holding that no work under the contract including mobilisation could be done without obtaining permission from PGCB and no compensation is recoverable from the petitioner under the contract, the learned Arbitrator acted beyond his jurisdiction in traveling beyond the terms of contract, inasmuch as the learned Arbitrator having not identified any breach on the part of the petitioner, the award was opposed to law and public policy inasmuch as the High Court Division did not understand the true perspective of the word ‘public policy’ and its role in setting aside the said award dated 29.08.2006.”

-

Mr. Ahsanul Karim, learned Advocate appearing on behalf of the appellant made submissions laying forth the grounds upon which leave was granted. He further submitted that the High Court Division should have considered that the claimant having himself been in breach of contract the learned Arbitrator completely misconceived section 73 of the Contract Act making Award of Tk. 1,11,60,000.00 in favour of the respondent. The learned Advocate also submitted that the High Court Division erred in not considering that the learned Arbitrator misconducted himself in not properly considering the provisions of the Contract Act and giving an award in favour of the claimant who did not qualify to make any claim at all since there was admittedly no breach of contract by the respondent (appellant herein). His final submission was that the learned Arbitrator acted beyond his jurisdiction in traveling beyond the terms of contract which were fundamental in any claim based on it. There being no breach on the part of the appellant the award was opposed to law and public policy, inasmuch as the High Court Division did not understand the true perspective of the word ‘public policy’ and its role in setting aside the said award dated 29.08.2006.

-

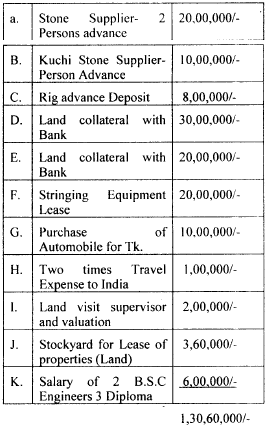

Mr. A.Y. Mosheuzzaman, learned Advocate appearing on behalf of the respondent made submission in support of the judgement and order of the High Court Division. In addition he submitted that the loss incurred by the respondent was due to part performance of the contract which was instigated by the appellant in terms of the Letter of Intent dated 10 September, 2004 and Work Order dated 28 October, 2004. It was at the behest of the appellant that the respondent mobilised materials and equipment as instructed by the appellant and, hence, the learned Arbitrator rightly passed an award in favour of the respondent. He further submitted that under section 43 of the arbitration Act, 2001 an arbitral award may be set aside only if it is opposed to the law for the time being in force in Bangladesh or if it is in conflict with public policy in Bangladesh. He submitted that in the instant case, since the award is neither opposed to the law nor is in conflict with public policy, and there is no allegation that it was induced by fraud or corruption, there was no ground for the appellant to seek an order for setting aside the award. He also submitted that the arbitration award is not liable to be brought under scrutiny before the High Court Division since that Division does not sit as a Court of appeal over the award of the learned Arbitrator. In support of his contention he referred to the decision reported in the case of Shahabullah (Md.) Vs. The State reported in 43 DLR, 1. He further submitted that the High Court Division is not at liberty to interfere with the award passed by the learned Arbitrator other than on the grounds mentioned above (as provided under section 43 of the arbitration Act, 2001). He submitted that the award of the Arbitrator could not be assailed by reassessing and reappraising evidence considered by the learned Arbitrator. In support of his contention he referred to the decision in the case of M/s. Sudarsan Trading Co., v. The Govt. of Kerala and another reported in AIR 1989 SC, 890 and in the case of The President, Union of India and another, v. Kalinga Construction Co. (P) Ltd. reported in AIR 1971 SC, 1646.

-

We have considered the submissions of the learned advocates appearing for the parties concerned and perused the impugned judgement as well as other evidence and materials on record.

-

The claim of the respondent in this case, which was contested before the learned Arbitrator appointed upon agreement of both the parties, is based on the LOI dated 10.09.2004 and a Work Order dated 28th October, 2004 which in turn reflected the arrangement between the parties, as contained in the Minutes of Meeting dated 5th August, 2004. In that meeting the appellant and the respondent discussed finalisation of a contract for the construction of a 230 K.V. Khulria-Bheramara-Ishurdi Transmission Line by the respondent as a sub-contractor. One of the terms agreed in that meeting was that the work order given to the respondent would be valid only if PGCB approved the respondent as a sub-contractor. This condition was again reflected in Column 10 of Article 8 of the Work Order dated 28 October, 2004. It may be mentioned at this stage that the respondent admitted that he did not take approval of the PGCB. On the other hand, the respondent based his claim for expenditure incurred in placing materials and equipment on the site in accordance with the Letter of Intent dated 10 September, 2004.

-

We find that the Letter of Intent (Annexure-C) contains a request by the appellant to the respondent to accept the Letter of Intent and “arrange mobilisation of all resources based on this LOI”. We note from the LOI also that there is a condition that the respondent was to arrange approval from PGCB before commencement of foundation work, i.e. before 1st October, 2004. The claim of the respondent is that on the basis of the LOI and Work Order it was pressurised by the appellant into mobilisation of materials and equipment.

-

At this juncture we note that admittedly neither any work was done nor any mobilisation commenced before 1st November, 2004. The respondent first wrote to PGCB for approval as sub-contractor on 4th November, 2004. In fact PGCB refused to accord approval to the respondent on 14.12.2004. It must also be borne in mind that the appellant was the contractor under PGCB and, therefore, without the approval of the sub-contractor (respondent) by PGCB, the appellant would be unable to complete its contract with PGCB through the engagement of the respondent.

-

However, the terms and conditions of the LOI, Work Order and Minutes of the Meeting are all factual matters which have been dealt with by the learned Arbitrator and which in our view cannot be within the ambits of either the High Court Division or this Division to consider. The High Court Division rightly observed that the arbitral award is generally not open to review by Courts for any error in finding on facts and applying law for the simple reason that it would defeat the very purpose of the arbitration proceedings.

-

The arbitration Act is a special law enacted with the aim of giving expeditious relief to parties who accede to the system of arbitration agreed upon in their contract and adjudicated upon in accordance with the arbitration Act, 2001. Under this Act the decision of the Arbitrator making the arbitral award is final and binding both on the parties and on any persons claiming through or under them. Section 39 of the Act provides as follows:

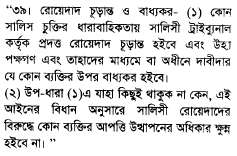

- The only ground of challenging the award is to be found section 43 of the Act, which provides that a challenge of the arbitral award is permitted only on the grounds set out in that section. Section 43 of the arbitration Act, 2001 has been quoted in the impugned judgement. For our purposes the provisions relevant for the instant case are as follows:

-

Thus, the scope of interference with the arbitral award is very limited as has been held in the cases cited by Mr. Moshiuzzaman. Whenever an award is challenged before any Court, the Court, i.e. either District Court or as in this case the High Court Division, does not sit on appeal over the decision of the learned Arbitrator. Therefore, the scope of considering the merits of the case and factual aspects is again very limited.

-

In the instant case the provisions of the arbitration Act relevant for our purposes, as urged by the learned Counsel for the appellant, are found in section 43(1)(b)(ii) and (iii). In view of the above proposition that the High Court Division does not sit on appeal over the arbitral award, the submission of the learned Advocate for the appellant with regard to fulfillment or non-fulfillment of the terms of the contract is somewhat redundant. The factual and contractual positions are matters for decision of the Arbitrator and as such, unless there appears to be gross illegality, neither the High Court Division nor this Division would enter into the merit of such arguments.

-

With regard to the question of public policy, the submission of the learned Advocate for the appellant, if we have understood correctly, is that it includes any decision by the learned Arbitrator without following the existing law of the country or traveling beyond the terms of the contract. In the civil petition for leave to appeal it was contended that any misinterpretation of a well settled principle of law or leading precedent or misreading and non-consideration of evidence amount to an act against public policy and that it means and includes also to ensure justice and rule of law.

-

The learned Judge of the High Court Division quoted the explanation in section 34 of the arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996 of India (“1996 Act”) which is similar to section 43(1)(b)(iii) of our arbitration Act, 2001, which provides that an award would be treated to be in conflict with the public policy of India, if the making of the award was induced or affected by fraud or corruption or was in violation of section 75 or section 81. The High Court Division then went on to suggest what might be considered public policy, but ultimately decided that “the application of the concept of public policy for the purpose of setting aside an award is rendered difficult.” The learned Judge concluded that the award was not patently illegal or so unfair and unreasonable that it could be labeled as being in conflict with public policy.

-

We also feel that a definition of public policy would make it easier to decide what would be considered as being in conflict with public policy. In the absence of such definition, we are to rely upon the usual meaning of the phrase ‘public policy’ which according to Black’s Law Dictionary, 18th Edition is: “Broadly, principles and standards regarded by the legislature or by the courts as being of fundamental concern to the state and the whole of society”. It could be said, for example, that if the decision of the learned Arbitrator would have a negative impact on the future of international agreements by foreign companies investing in Bangladesh, then such a decision could be terms as being in conflict with public policy. However, in the facts of the instant case we do not consider that the contract entered into by the parties or the award made by the learned Arbitrator has any impact on the state and the whole of society. We also cannot agree with the submission of the learned Counsel for the appellant that a decision contrary to the law of the country is necessarily in conflict with public policy an envisaged by the Act, 2001. That would be an illegality pure and simple. It would be giving too broad a meaning to the phrase ‘in conflict with public policy’ to include decisions which are contrary to law, or where the learned Arbitrator has traveled beyond the terms of his reference, or has misinterpreted a principle of law or precedent, or for misreading or non-consideration of evidence. These matters can be considered as matters relating to propriety, but are not, in our view, matters relating to public policy.

-

The appellant before us raised the issue before the High Court Division as well as before this Division that the respondents did not fulfill their part of the contract, inasmuch as they were unable to obtain approval from PGCB and, therefore, according to the terms of the Letter of Intent and the Work Order they could not have commenced the mobilisation. Furthermore, it was submitted that since there was a stipulation that the Work Order for the foundation would commence by 1st of November, 2004, that having not been done, and the respondent having applied for approval from PGCB on 4th of November, 2004, (page 152 of the paper book) they were already in breach of the contract and, accordingly, the appellant rightly terminated the contract. It was pointed out by the learned Advocate for the appellant that the learned Arbitrator found that till 12.01.2005 the claimant could not secure the approval of the PGCB as required by the agreement. The learned Arbitrator observed that the Claimant admitted that he could not procure the approval of the PGCB. As such, the claimant failed to perform an important term of the contract and for this failure the respondent No. 1 (appellant herein) was entitled to terminate the contract as per the term of the contract. Accordingly, the learned Arbitrator found that the order of termination of the contract between the parties by respondent No. 1 (appellant herein) has been according to law and the terms of the contract. This finding of the learned Arbitrator is not amenable to challenge before any Court.

-

On the other hand, the respondent (claimant) claimed before the learned Arbitrator as well as before the High Court Division and this Division that it was entitled to claim damages for incurring expenditure towards facilitating the work with which it had been entrusted under the contract and as such, mobilisation of resources for commencing the actual work, was rightly claimed. In this connection the learned Arbitrator relied upon the decision in the case of Anglia Television Limited v. Reed reported in 3 All ER (1971) 690. The respondent relied upon this case as well as the materials on record which tend to show that it at the insistence of the appellant that it commenced mobilisation of equipment and materials.

-

One other point argued before us was that the respondent was required to submit a Performance Guarantee and Bank Guarantee before the contract would take effect and that no such guarantee was furnished. It was the claim of the respondent before the learned Arbitrator that due to the failure of the claimant to furnish bank guarantee and to obtain approval of PGCB which were both preconditions of the contract, there was no contract at all.

-

On this issue the learned Arbitrator observed that had there been no contract, the respondent No. 1 (appellant herein) would not have issued the Work Order and would not have issued instructions to the claimant to mobilise resources. The learned Arbitrator relied on the principle laid down in the case of Anglia Television Limited v. Reed reported in 3 All ER (1971) 690 where it was held that the claimant is entitled to recover the damage for expenditure which it claimed to have incurred under mutual arrangement with the respondent No. 1 (appellant herein) in order to facilitate the work under the contract.

-

The High Court Division agreed with the decision of the learned Arbitrator so far as the claim of the respondent is concerned save and except the claim for 50,000007- Taka in respect of “land collateral with bank”.

-

Before the High Court Division as well as before this Division learned Counsel for the appellant made a submission to the effect that only the person in breach of contract is liable for the loss and damage caused by the breach of contract. He submitted that the learned Arbitrator wrongly applied the principle of the decision in Anglia Television Limited v. Reed. He pointed out that in the case under reference the defendant entered into the contract knowing that expenditure had already been incurred by the plaintiffs and, therefore, the defendant must have contemplated, or it was reasonable to impute contemplation to him, that if he broke the contract the expenditure would be wasted.

-

Let us consider Section 73 of the Contract Act which provides as follows:

“73. Compensation for loss or damage caused by breach of contract-when a contract has been broken the party who suffers by such breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby which naturally arose in the usual course of things from such breach, or which the parties knew, when they made the contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it.

Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach.”

- Kamaluddin Hossain J. (as his Lordship was then) in Amin Jute Mills vs. M/s. A.R.A.E. 28 D.L.R. (AD) 76- referring to section 73 of the Contract Act observed as follows:

“An analysis of section shows that, when it is found that a party to a contract is in breach, he must pay compensation for the loss or damages caused by the breach to the other contracting party. That is the principal consideration.”

-

It was held in the case of K.M. SHAFI LIMITED V. GOVERNMENT OF BANGLADESH AND OTHERS reported in 1983 BLD (AD) 109 that in a dispute over a contract the Arbitrator is the sole judge. Per Badrul Haider Chowdhury J. (as his Lordship was then), “Unless the award of the Arbitrator can be assailed on one of the three grounds mentioned in section 30 of the arbitration Act the long line of cases show that the Court will not interfere even though courts may take a different view of the interpretation of the particular terms of contract. This is a sound principle. Otherwise such disputes should be brought within the jurisdiction of the civil court and thereby opening a flood gate of litigations nullifying the very spirit of the arbitration as mentioned in the arbitration Act” (His Lordship was referring to Act X of 1940).

-

Learned Counsel for the appellant submitted that when the learned Arbitrator found that the claimant (respondent herein) was himself in breach of contract and that the claimed loss and damage was not caused by the breach of the appellant he should have held that the claim is not sustainable.

-

The provisions of section 73 of the Contract Act are quite clear, inasmuch as whenever there is any loss or damage caused by the breach of a party to an agreement then the other party (the innocent party) who has incurred the loss as a result of the breach is entitled to receive compensation for any loss or damage. In other words, in the facts of the instant case, had it been found that the appellants were in breach of contract and the respondents (claimant before the Arbitrator) had incurred loss and damage as a result of the breach, then surely there would have been a claim by the respondents. But in the facts of the instant case it is abundantly clear that the learned Arbitrator found as a matter of fact that the claimant was in breach and that the termination of the contract by the appellant was according to law and the terms of the contract. Having decided this issue against the claimant, clearly the decision in the case of Anglia Television Limited v. Reed no longer remains applicable. The principle in the said case, i.e. the ability to claim to the extent of loss and damage incurred before contract still stands good, but it must be subject to the provision of the Contract Act, i.e. that the person who is in breach will be liable to make good the loss of the person who suffers as a result of the breach. Moreover, in that case the defendant was aware at the time of entering the contract that expenditure had already been incurred for which he would be liable in case of breach by him.

-

We are, therefore, of the opinion that in order to be entitled to claim for a loss incurred due to a breach of contract, the claimant must prove that the loss incurred was due to the breach of the defendant and that the loss incurred was within the contemplation of the defendant at the time of signing the contract.

-

Since in the facts of the instant case the finding of the learned Arbitrator was that it was the claimant who was in breach of the contract and not the defendant, clearly the claimant does not qualify to claim under section 73 of the Contract Act. In this regard we may refer to the decision in the case of Bangladesh Power Development Board and others vs. M/s. Arab Contractor (BD) Limited and others, where it was held that:

“An analysis of section shows that, when it is found that a party to a contract is in breach, he must pay compensation for the loss or damages caused by the breach to the other contracting party. That is the principal consideration”.

-

In the instant case the clear finding being that the appellant was not in breach of the contract and had rightly terminated the contract due to breach of the terms by the respondent, no question of liability will arise against the appellant. This being a fundamental question of law and the learned Arbitrator having totally overlooked the existing law on the issue, the arbitral award was rightly challenged under section 43(1)(b)(ii) of the arbitration Act.

-

In view of the above discussion, we find merit in the appeal which is allowed without, however, any order as to costs. Accordingly, the impugned judgement as well as the Award of the learned Arbitrator are set aside.